Brita city

Bioswales, blackwater, and benthic nets. Microbial fuel cells, hydroponic disinfection, and pervious pavement.

Were you thinking about these things when you were in college? I certainly wasn’t. Perhaps I should have been, because the student teams in the History Channel’s City of the Future Engineering Challenge sure seem like they have bright futures ahead.

Picking up on the popularity of their “Engineering an Empire” series, the History Channel last year held a design competition in LA, Chicago, and NYC. Professional design teams had one week to design a vision of their city 100 years in the future in such a way that would be sustainable much beyond.

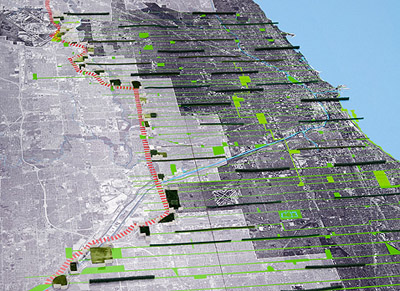

The winner in Chicago was Urban Lab, a small outfit on the south side whose Growing Water submission presented a Chicago infrastructure that recycles 100% of the water it needs by un-reversing the flow of the Chicago River back into Lake Michigan, resurrecting the (currently) century-old idea of an Urbs in Horto “Emerald Necklace” of parks ringing the city proper, and carving latitudinal waterways alongside “eco-boulevards” to make the whole city-sized water filter work.

That was sorta the easy part. The heavy lifting was left for the students in the second phase who actually had to present the engineering behind it all. As a sponsor of the event (with a keen interest in promoting engineering, math, and science) IBM was asked to provide a judge for the second phase. This was me. I was elated. I wasn’t at all qualified, but I have been writing about the subcontinental divide, reversed river, and future Chicago here for a long time. The blog as street cred.

Undergraduate engineering student teams were fielded by the Milwaukee School of Engineering, Purdue University, U of I Urbana-Champaign, two from U of I Chicago, and Northwestern University. The presentations were simply remarkable. These kids — and they were kids to be sure — had put an amazing amount of time and thought into the tricky real-world problems of re-architecting a city at its most basic level. None of this was done for course credit.

Prior to the presentations the judges received ample supporting documentation for each solution: dozens of pages of equations backing up claims, diagrams, 3D renderings, and a bounty of specialized words to make the verbophile delight for hours. Advective. Biomimicry. Turbidity. Effluent. I loved it all.

The essence of the challenge in engineering Urban Lab’s design was how to design the filtration of the water in the terminal parks and along the eco-boulevards east of the subcontinental divide. Most of the teams focused on how this filtration would happen. Others also stressed the challenge of separating graywater (wastewater with everything but poop), blackwater (poop), and potable water while being able to accommodate the “100-year-storm” (Chicago, though above sea level, is essentially a swamp). Still others focused on the Urban Lab sidenote that existing santitation tunnels (not needed in their design) could be used for expanded mass transit. One team went into great detail about a Chicago Maglev train. This might be a great next project for the CTA as their current Brown Line expansion will likely finish up around 2106.

The team from UIUC won the competition with their notion of EcoTowers — residences at the terminus of eco-boulevards that pass graywater through a “biomimetic forward osmosis membrane bioreactor.” Duh. Of course they do. The towers themselves provide further filtration by running a curtain of nearly-clean water down the windows of the highrises for UV disinfection. Like living under a waterfall or inside the Beijing Olympic natatorium. Brilliant.

Chicago has a very long way to go to approach anything like this design, of course. Green roofs are a start, I suppose. Just glad people are working the problem. Even more glad that career-minded students are taking it so seriously. Bravo to all the teams.

See also on Ascent Stage: City of the Future and 10 Visions, an exhibition from the Art Institute