The Ampcamper How-To

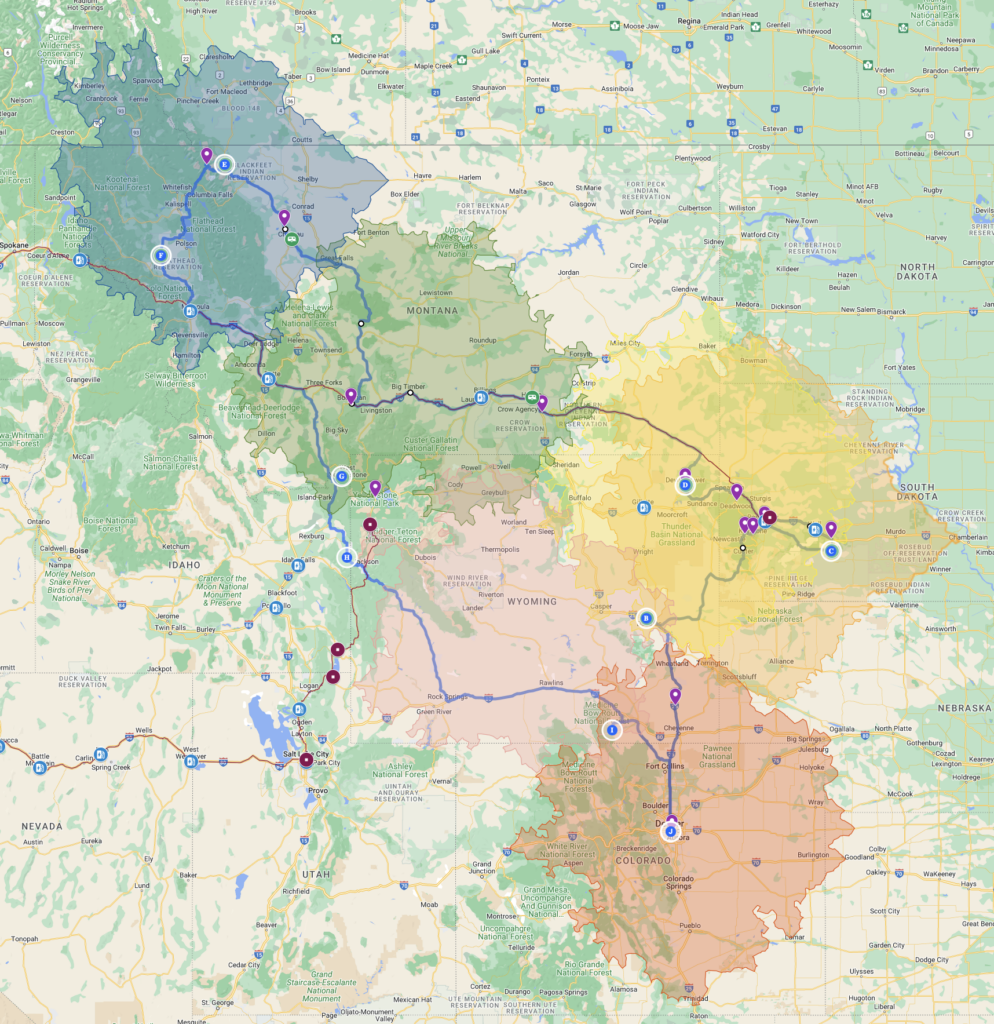

This is a tale of towing a camper trailer 4,000+ miles with an electric vehicle.

When the summer vacation idea to tool around the Western USA in an RV first was hatched it was pretty traditional. We didn’t own an RV, so we’d rent one, probably a big gas-guzzler that we’d drive around like a bus. But as I started thinking about how I liked to roadtrip — which is to say, stopping at every World’s Third Largest Ball of Twine I come across — a big rig seemed impractical. I would have chosen towing out of the gate but I couldn’t quite get over the downside that we’d all be trapped in a car for large parts of the trip. Eventually the tow setup won out when my college roommate offered his 30-year-old (but redecorated!) Sunline trailer. Seventeen feet of old school camper trailer — for free. I was in.

I knew that my Tesla Model X could tow up to 5000 lbs (about twice the Sunline camper GVW empty) so that wouldn’t be a problem. And thanks to a drunk driver in January destroying my previous car I had a relatively new Model X with 75 miles more range, 350 miles total. This seemed like the perfect setup … except for the charging.

The charging was worrisome for a bunch of reasons:

- All Level 3 DC fast chargers (what Tesla calls “Superchargers”) require you to back in to the stall for charging very close to the terminal, something impossible to do when towing anything . As far as I can tell this is because the amperage flowing through the very thick cable disallows the length needed to charge a car pulled in front-first. (Or at least degrades the throughput so much as to make it not as fast.) Tesla occasionally puts a single charging stall perpendicular to all the others for the very situation I would be in: towing something that prevents backing in. But these perpendicular stalls are very rare and often occupied by people who simply don’t want the hassle of backing in.

- Given our schedule I would need overnight Level 2 charging (what Tesla calls “Destination Charging”). Many hotels have this; almost no campgrounds offer this. We weren’t staying in hotels.

- Most of the states we would be visiting are electric vehicle charging wastelands, Montana and Wyoming in particular. There are many reasons for this — lack of density, red state love of the internal combustion engine, and basic market dynamics — so I knew even if the perfect setups existed they would be few and far between.

- National parks themselves are fairly bereft of infrastructure, period. That’s part of the point. Very large parks (like Yellowstone) actually do have some gas stations and recently Rivian has started installing Level 2 chargers at some in-park lodging (such as The Ahwahnee in Yosemite), but for the most part once you’re inside a national park you are off the grid quite literally.

So how did we do it?

For the Level 3 (on-the-route) fast charging we had backup plans upon backup plans. I visited every Streetview image I could find for every possible DC charger with 175 miles of main destination points (sites or campgrounds). Sidenote: using a site called Smappen I created somewhat beautiful “chargeshed” (not a word, made it up) maps showing me roughly how far I could get before we were doomed.

So from those Streetview images I knew the physical layout of every possible charging stop. This enabled me to plan for one of the following scenarios:

- Pull into a perpendicular charger (photo above), showering praise on the gods of electricity. There were maybe three of these total on the route.

- Pull forward past the chargers if no curbs or bollards were present. Only the oldest charging stops have no curb and I only ever encountered such a setup on a test run. None on the actual trip.

- Pull parallel across a bunch of empty stalls like a complete asshole. This only works in specialty situations when no one is charging and there is a ton of extra room to the left of the leftmost stall. You obviously can’t leave your vehicle if you do this, since others could show up and need the chargers you are now blocking. I did this a few times like a complete asshole.

- Unhitch. The option of last resort. We were forced to do this a bunch of times, though by the second week my daughter (“The Hitch Bitch” thank you very much) and I were as fast as a Formula One pit crew getting the rig unhitched and hitched back up.

In total we charged 31 times at Level 3 chargers, all Tesla except once at an Electrify America station. The latter are rolling out slowly, but if you can get a “Hyper” stall they charge even faster than the Tesla Superchargers.

Of note is that I almost never performed a full top-up at these stops. Pretty quickly I came to understand exactly how far I could go in most terrain towing our load. The car is rated at 350 miles with a full charge. On two test runs I basically calculated that range was cut in half towing, so 175 miles. This obviously was variable based on elevation increase and decrease (and headwind/tailwind, but c’mon), but the car itself started recalculating range based on “knowing” that we were in Tow Mode. It was fairly accurate, but to be extra safe I was mentally calculating that I would need 3x of the total distance to my next charge. If you’re doing the math at home this means that I would not schedule any stop further than about 110 miles out, even though I probably could have. This worked … until it didn’t.

We were ¾ of the way from Hot Springs to West Yellowstone, Montana, the second longest run of the trip, beautiful but empty. We juiced in Butte and, according to the onboard calculation, were set to make it on the wattage equivalent of fumes. But something didn’t seem right. There was a 2000’ elevation gain between us and Yellowstone that I wasn’t sure the onboard range calc was factoring in. With no towns at all en route the only solution was to find something, anything that would give us at least a 220v connection. (I refused to consider plugging into a 110v outlet — what’s known as Level 1. We’d be there charging for days.) Short of stopping at someone’s home and asking to use their washing machine electrical hookup connection (don’t laugh, we did that — more on that below), the only option was to find an RV campground.

And here we have the real hack of the trip. RV campground power is really what made it all work. You could argue that RV campgrounds exist in the first place for only two reasons: they provide a place for recreational vehicles to receive power and to dump waste. In test runs prior to the trip I confirmed that with the appropriate physical adapter I could adequately achieve a Level 2 charge overnight from a normal 50 amp RV hookup. Even better, most campground pedestals provide two connections — one for 50 amps and one for 30 amps — so I could also power the camper (though I brought a splitter just in case).

So this was the solution for a little extra juice on the uphill run to West Yellowstone. We found an RV campground en route (ahem, the only RV campground en route) and pulled in. It was almost full but the office was closed and the whole park was strangely devoid of people. I think a storm had just passed through and everyone was still hunkered in their campers. We found an empty stall, hooked up, and started charging. Problem solved.

I didn’t invent this hack. People have been charging electric vehicles at RV campgrounds as a last resort for a while, but usually this is done without an accompanying recreational vehicle behind the EV — a sure tip-off to campground management that you’re not paying for the privilege. The big campground companies, like KOA, have caught on and have official policies forbidding charging electric vehicles from RV pedestals. They even say you can damage your vehicle doing so. And yet, I hooked a voltmeter to a pedestal on a test run and saw nothing out of the ordinary. And I trusted my car to prevent catastrophe from an unstable connection. (I had in the past experienced this trying to do Level One charging at a very old house with wonky wiring. The car detected it immediately and said nope.) A very few campgrounds do actually provide Level 2 chargers, but these are completely separate from the camping slots (requiring unhitching and unloading, boo).

And that’s really, simply how the trip happened: every night at our campgrounds we charged the car fully via the RV electrical pedestal (Level 2). We did this 25 times.

Importantly charging this way requires the 50 amp connection. 30 amp will take far too long. I’d advise having a splitter just in case as in at least one instance we shared a pedestal with the RV next to us. No campground employee ever made us disconnect and I am certain we were noticed. Hard to miss the sole electric vehicle in the park towing an old camper painted like a Colorado flag. Indeed, lots of campground folk would come to our site and ask how we were doing it, but they were more interested in the towing performance than our charging travails. To everyone other than the corporate management of RV campgrounds charging an EV like you’d juice up your camper battery just makes sense.

There’s such crossover potential between RV communities and EV owners. To some degree if you own a motorhome or a camper trailer you plan your route based on the availability of electricity. Where to power/recharge at night is a factor in planning, even though most rigs can boondock off-grid for a few days. Not only that, most experienced RV people have developed at least a rudimentary understanding of matters electrical (adapters, voltage vs amperage, etc). As the federal government looks to provide incentives and investment for the build-out of charging infrastructure, I suggest focusing some of the attention on RV-friendly communities. They already have the knowledge and some of the infrastructure. I have no data to back this up, but my guess is that culturally these are some of the most gasoline-loving communities in the nation … with the twist that they know first-hand how important electricity is to their lifestyle.

The tipping point in the RV/EV crossover may be the widespread availability of bidirectional charging. Bidirectionality is the ability of a vehicle to provide its battery charge externally — to a power strip, a home, or even to another vehicle or camper trailer. Annoyingly Tesla does not do this (except to power the brake/turn/running lights on the camper), but the new Ford F-150 Lightning does. And there sure are a lot of regular F-150s in an RV campground. Boondocking potential aside, it makes sense that a camper trailer setup has a single battery source. You plug in at the campground and everything charges at once. Add some intelligence into the connection and you could programmatically make sure that you never use too much juice in-camper to prevent the vehicle range needed for the next day.

The RV/EV crossover has not really begun (though there are attempts), but it will and I think there will be no looking back. Campgrounds must see the writing on this particular wall. The good news is that there really is no need to install separate EV charging stalls at campgrounds. The wiring is already there. What campgrounds need to figure out is their total electrical capacity and the financial model to make it feasible.

A few final notes. One night we used Harvest Hosts — basically Airbnb for RVs where a farm, ranch, winery, etc offers one or two slots for overnighting. Generally these hosts do not have traditional hookups. We stayed at the lovely Ring of Horns bison ranch whose owner allowed us to run a very long extension cord and 220v adapter into her house to take advantage of her washer/dryer connection. I travel with a trunk full of extenders and converters so this wasn’t a problem. But you need an accommodating host (and some washer/dryer setups run off of 110v so your mileage may quite literally vary).

You may be wondering where solar power was in this Rube Goldberg setup. I considered it, but solar at the scale of photovoltaic panels that a vehicle or camper can accommodate just won’t do it at this point, especially since no vehicle I know of can charge while driving (i.e. when the sun is shining) and most charging needs to happen when parked overnight.

Again, towing was not an issue. It was smooth and uncomplicated, apart from one hiccup in automatic range calculation. Given the torque of electric vehicles with no real drive train I did dial the acceleration back just to take some strain off the hitch. And of course no autopilot, because I barely trusted myself to pilot this rig let alone the car AI.

We traveled 4,192 miles (approximately the distance from Honolulu to Chicago) and consumed 2,134 kilowatt-hours of power (approximately the average consumption of a typical American home over two months). The majority of this electricity was generated using fossil fuels, I’m quite certain. But with 2.5x the miles for electricity created from fossil fuel versus what you’d get burning it in an internal engine, I’m pleased with our footprint. Plus, zero emissions. Feels good to be inside a national park and know you’re not contributing to anthropogenic climate change — at least at that very moment.

Would I do this again? Absolutely if I could solve the Level 3 back-in problem. There are some sketchy after-market extensions available, but I am dubious as actual electrical engineers in the comment sections of these products basically say absolutely do not do this. But if a real, tested solution appeared I would roadtrip like this again in an instant. Less important, though ideal, would be owning a vehicle that allowed real two-way charging. I’d love to not worry about two batteries on a roadtrip.

And that’s how I hauled myself, two teen girls, an 80 lb dog, and a whole load of crap across six states in twenty days using an electric vehicle.