Land of Fire and Ice

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested.

Greetings travelers! I hope you are prepared for an adventure — properly dressed in layers, extremities covered, feet shod in crampons — because we are going to Iceland. I’ve compiled an itinerary by watching every horror movie ever to come out of this small island nation. But before we take that excursion let’s pack our bags with some context.

Iceland is Hawaii upside-down, a largely self-contained ecosystem in the middle of a vast sea perpetually remaking itself directly above a hotspot vent in the Earth’s mantle. Like Hawaii Iceland has been a prize of sea-going conquerors through history: the Vikings of course, but also the kings of Norway and Denmark, and even the occupying forces of Britain and the USA during World War II.

Both geologically and culturally Iceland straddles North America and Eurasia. In addition to being the morphing volcanic crown of the mid-Atlantic, Iceland exists right on the boundary of two tectonic plates, just kissing the southernmost boundary of the arctic circle, and slowly moving away from their one-time embrace. This position between two worlds enabled Icelander Leif Erikson to discover what would come to be called North America 500 years before Christopher Columbus — though Leif and his compatriots left behind only tool shards rather than genocidal European pathogens.

Icelanders know how to live between worlds. For example, some 35% of people in Iceland believe in elves. Called Huldufólk, these “hidden people” appear human but live in a parallel world overlaid on our own, popping in and out of our reality at will. How can you tell them from us? It’s subtle. Huldufólk have a convex rather than concave philtrum below their noses. So, yes, I spent much of my recent trip to Iceland staring intently at people’s upper lips. Awkward and uncomfortable for all parties involved, but this is my responsibility as the director of this terror travel agency.

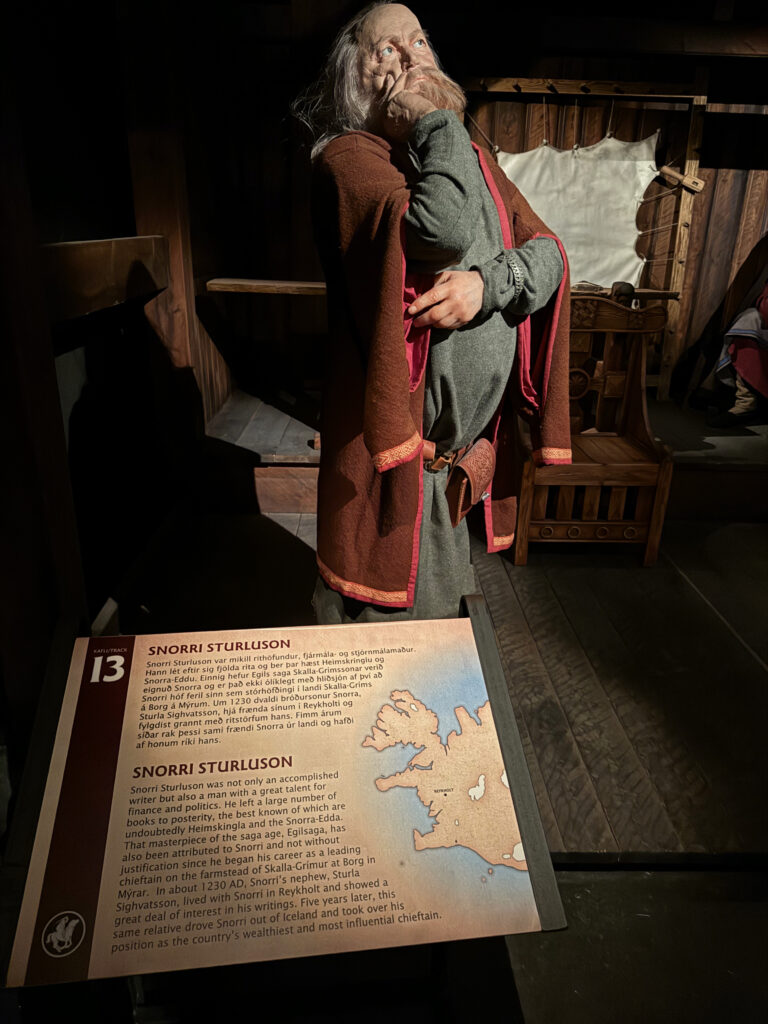

Iceland hosts all kinds of supernatural creatures, most of which you will find in their amazing literary legacy known as the sagas. Part history, part genealogy, part mythology, these tales are unique to Iceland and date to the 9th through early 11th centuries. If interested look up Snorri Sturluson, Iceland’s revered national poet and historian. Actually just say his name — Snorri Sturluson — and feel a smile come to your face.

The sagas feature draugr what we’d call “ghosts”, the aptrganga literally “again-walkers”, the haugbúi literally “mound-dwellers” as well as trolls, giants, witches, sorcerers, and devils. All of these nightmares fall into the category of reimleikar or “hauntings”. Interestingly what often gets translated as “ghosts” in Iceland are actually corporeal. These things have physical bodies and can do physical harm. There’s also the legend of the Útburður — literally the “out-carried”, babies left outside to die of exposure — unwanted because of rape, incest, or conception out of wedlock who return as ghosts. That one kinda messed me up.

So you pause here with me on our journey, travelers, and ask the obvious question: Are all the scary things in Iceland fantastical? Aren’t there any humans to be feared? The answer is: not really. Iceland is consistently ranked the #1 safest country in the world. (The USA comes in a 131 out of 163.) And there is honest-to-Odin only a single known serial killer in all of Icelandic history. In the late 16th century a farmer named Axlar-Björn was convicted of killing 9 people, mostly boarders and farmhands, variously by axing them to death or drowning them. He likely killed more than 9 as a search of his farmlands yielded many more bodies. Ol’ Axlar was executed for these crimes by first having his limbs shattered with a sledgehammer, then his privates severed and tossed to his pregnant wife, then he was beheaded and dismembered — each severed body piece receiving its own display on a stake. His children weren’t much better people, frankly. Years later the last words of his son who was being executed for robbery and murder were “If I were free I would kill you all and eat your flesh.”

But honestly other than that particular family, there isn’t much to be afraid of in Iceland … except Iceland itself. That is, literally, the ice and the land.

Let’s start with the darkness. Like all places as far north (or south) as Iceland much of the year is very dark. The sun barely peeks above the horizon in the winter. It’s a gloomy vibe, not quite pitch, but certainly unsettling — like a permanent eclipse. As a sidenote, this seasonal darkness may explain why Iceland and Finland have the highest percentage of metal bands per capita in the world. And not just Viking metal. This is perhaps obvious if you have ever tried to pronounce an Icelandic word as basically every other term in an Icelandic dictionary would make a great black metal band name. And Iceland officially does not allow foreign terms in its language. So when a new concept emerges, like the computer did in the 1940s they make one up. In this example, they joined the term for number (tala) and witch-doctor or prophetess (völva) A computer is thus a number witch-doctor and the new word is … Tölva. Which is my last name. I am, unfortunately, 0% Icelandic.

But let’s get back on the path. Iceland is called the land of fire and ice and that’s no marketing slogan. Well, actually it is, but it is for truth. There are more than 30 active volcanos ripping their own scabs from the land. At any given time quite a few of these are actively spewing lava or scalding mud and ash. In fact, when I was there a few weeks ago we witnessed a crater field which had been dormant for a few months fissure and begin erupting right before our eyes. Icelanders live with this peril, indeed embrace it as the source of many good things, but not incautiously so.

In fact what worries Icelanders more than volcanos is what sits on top of them, which is usually glaciers. We all know that our planet’s glaciers are melting at a worrying rate, but detonate a geothermal bomb underneath them and, well, they melt really quickly. In an eruption all that molten rock and ash mixed with millions of cubic acres of now-melted ice cap hastily seeking lower ground will ruin your day right quick. And Iceland’s biggest city Reykjavik sits on one of the most volcanically active peninsulas of the entire island. Iceland would not exist without vulcanism and one day, hopefully later rather than sooner, it will likely cease to exist because of vulcanism.

Then there’s the sea itself. The North Atlantic is an angry place. Got an unsinkable ocean liner? It’ll take care of that. The waters are rough, rogue waves are commonplace, the whole thing is plied by an unruly fleet of icebergs constantly calving off from increasingly-unstable glaciers, and the water, naturally, is freezing. Typically if you find yourself bobbing in said water you will live as many minutes as the number of degrees celsius the water is above freezing. So let’s say you were lucky enough to spill over into a warm patch of ocean, say 5°C/40°F, you’d live for approximately 5 minutes. As a darkly humorous aside, there is a huge culture of swimming pools (indoor obviously) in Iceland. This is a legacy of a realization in the early 20th century than an above-average number of sailors were drowning due to incidents just offshore that otherwise would have been close enough to swim to safety. Thus Iceland made it mandatory — which it is to this day — to be able to swim. It’s part of childhood educational curriculum. I pause to wonder why the people of a nation literally surrounded by the ocean, criss-crossed by waterfalls, and in a constant state of glacial melt sogginess wouldn’t have previously thought knowing how to swim was important, but who am I to say?

One last way that Iceland wants to kill you. All the aforementioned geological instability produces a lot of earthquakes. No need to delve into that particular kind of calamity except to note that Iceland is one of the only places on earth where there is a non-zero chance of being crushed by tectonic plates underwater. The Silfra Fissure in beautiful Thingvellir National Park is a glacial lake that straddles the cleft made as the North American and Eurasian continental plates slowly move apart. It’s a popular snorkeling and diving site where you can touch both plates at once. And if there’s an earthquake while you’re down there, welp, that’d be a pretty great way to go, no? Reclaimed by earth itself. And yes, it was cold in that drink: 35°F. If not for our drysuits my son and I would have spent our last 1.5 minutes together.

OK let’s catch our breath on this hike. In and out. In and out. We’re warm, we’re dry, nothing is erupting on us, let’s move on … to horror movies.

Here’s the thing. Given the landscape, Iceland seems like the perfect place for the horror imagination to run wild. Match a hostile environment with centuries of ghost storytelling tradition and the fact that it’s exceedingly easy to become isolated in such an unpopulated place. But honestly horror just isn’t a huge genre in Icelandic cinema. This may simply be due to size. Iceland just doesn’t produce as many movies as, say, the much larger, much more populous countries of Sweden or Norway.

But this is an opportunity for our itinerary, my weary travel buddies! It occurred to me that I might be able to watch the entire output of a single country’s horror film industry. And that’s exactly what I attempted to do over the last few months. Did I succeed? Well … I watched 11 films, but there are a few festival-only shorts, made-for-TV specials that were never rebroadcast or put online, and at least one film which does not exist with any subtitles or dubbing. So, no, I did not see everything. But I saw almost everything and certainly the best things.

First a note on Jóhann Jóhannsson, the peerless Icelandic composer. (His albums Englabörn, IBM 1401, and Fordlandia will change your conception of what classical music can do.) For our purposes though it should be noted that Jóhann wrote the music for the 2018 revenge bloodbath Mandy. It was his final work prior to dying of heart failure at the age of 48. If you’ve seen Mandy you know how crazy its score is. Panos Cosmatos, Mandy’s director, said of Jóhann “[he] went above and beyond, and I suspect to the limits of his sanity, to make the music for this movie.” Growing up surrounded by Iceland’s black metal music scene and having seen and loved Cosmatos’ previous film Beyond the Black Rainbow, Jóhannsson reportedly pled his case for the job saying “Holy shit, you guys are making something … that is in this nightmarish, psychedelic metal world that I was born and bred on”. Cosmatos hired him and said “I basically wanted it to feel a little bit like a disintegrated rock opera, and Jóhann responded to that. We developed a kind of shorthand almost immediately.” The movie was made, Jóhann died tragically, and now Cosmatos says he cannot bring himself to revisit the soundtrack. “I’m almost afraid to listen to it in isolation, because I still have emotional strands attached to it.” Have a rewatch — or more specifically a re-listen — of Mandy if you want to get a real flavor of Icelandic horror genius.

These 11 films are representative both of the thematic diversity of Icelandic horror and in various ways are uniquely Icelandic. Here we go!

Reykjavik Whale Watching Massacre (aka Harpoon, 2019)

This splatter shlock features a cameo from Iceland’s most famous — perhaps only legitimate — horror movie celebrity: Gunnar Hansen. That’s right: Leatherface. (Gunnar’s family moved to the USA when he was 5-years-old and the rest is history.) In this movie I learned that there are good reasons Leatherface was non-verbal in the original film only some of which have to do with the story itself. Hansen is just not a good actor. The plot finds a group of tourists stranded on a malfunctioning whale-watching boat who are picked up by a bunch of homicidal whalers running what amounts to a floating torture chamber. The whole thing is weirdly xenophobic with lots of uncomfortable stereotypes about the different nations of the tourists. There are some decent kills, including with harpoons, but this movie goes on for a least one act too many. It was already overly-long when it occurred to me that I, the viewer, had not seen a single whale. Fear not: stock footage to the rescue! There is indeed one kill from an orca. If this were shot on film you could probably see where this scene was stapled onto the existing celluloid reel.

Tilbury (1987)

This made-for-TV movie is classic WTF-did-I-just-watch? Based on the folk belief in a tame imp called a Tilbury which would suck milk from other people’s cows, return to its owner (almost always a woman), and then disgorge butter for her. When not stealing milk for re-processing the Tilbury feeds from a nipple inside its owner’s thigh. Oh and these imps are brought to life using communion wine served between its owner’s breasts. With that all as preface, it’s no surprise that this the visuals in this movie are vile. The story follows a modern day Tilbury conscripted into the British occupying forces during WWII.

Thirst (2019)

Billed as “MOST BAD-ASS GAY VAMPIRE ZOMBIE SPLATTER MOVIE YOU’LL EVER SEE…EVER”. Not four minutes into this film — which I’ll note that I watched on an airplane — we get screaming, gory vampire fellatio. This is so not a movie to watch on an airplane, certainly not with strangers next to you. It basically follows an elderly vampire who kills by ripping his victims’ penises off. Clearly this is done for comedic effect. At one point he even eats a penis in a hot dog bun. Not surprising when you consider that a top ten tourist attraction in Reykjavik is the Iceland Phallological Museum — a gallery of preserved penises and penis ephemera from various species. Thirst itself is a decent film and super gory, particularly a scene when a person is ripped in half top to bottom with the vampire’s bare hands in the snow. It’s part detective story, part commentary on Christian cults. But mostly it’s just goofy fun.

Lamb (2021)

Maybe the best movie I watched on this journey. It’s quintessential folk horror and apparently the highest grossing Icelandic film (of any genre) to date. Featuring Noomi Rapace who you may have first seen in Prometheus. Set on a farm in rural Iceland the style is ultra-realistic, beautiful and minimal, with no soundtrack. Noomi and her husband nurse an ill, hybrid newborn lamb to health, keeping it indoors, nursing it with a bottle, swaddling it to sleep in a bassinet. Hybrid you say? Yeah, it’s half human, but not like a centaur, just some of its limbs. It is bipedal though which is disturbing enough having a toddler with a lamb head running around the house. The lamb’s mother keeps showing up looking for it. Noomi has grown attached to her new “baby” so she kills and buries the mother lamb. This turns out to be a very bad idea. An excellent movie, but don’t expect to leave this movie with a warm fuzzy feeling.

Graves & Bones (2016)

This film is partially a response to the financial crisis of 2008 which hit Iceland abnormally hard — three banks failed, the largest economic trauma to any country relative to size. It opens with a little girl, Perla, stopping the swaying of someone we later find out was her father who has hanged himself. Gunnar is awaiting the decision on his appeal of a conviction for financial fraud — it was Gunnar’s brother, also connected to the fraud, who hanged himself, Perla his daughter. Gunnar and his wife head to a country house to assume responsibility for their now-orphaned niece. It’s a ghost house, of course, but more than that this is a movie about a marriage falling apart over grief — and an external financial crisis — which manifests in horrific ways. The juxtaposition of martial strife bordering on combat and elements of the supernatural are surprisingly effective and affective — it was tough to watch. Eventually you learn the backstory of the house and it all crescendos into a satisfying if bleak climax.

It Hatched (2016)

Another story of a childless couple in rural Iceland who unexpectedly get a baby, as in Lamb, which turns out poorly for everyone involved. Two isn’t a trend, but I’m still trying to figure out if there’s something deeper going on. In It Hatched, a couple moves from Nashville to a place way out in the middle of nowhere in Iceland. Turns out there’s a pit to hell in their basement from which emerges a ghost-devil who impregnates the lady of the house. She eventually gives birth to an actual egg, which of course hatches a seemingly normal baby, at least at first. This film has real promise with setting and premise, but the acting is odd and suffers from pacing issues. Scrambled, you could say.

Bokeh (2017)

Remember The Langoliers by Stephen King, a short story turned mini-series about a guy who wakes up from a nap on a flight and 90% of his fellow passengers are gone? That’s Bokeh, except it’s American tourists, Jenai and Riley, in Iceland who wake up one morning (after watching the northern lights the night before … in the summer, somehow) and there isn’t a soul left around. It’s a great conceit in any context, made especially so set in Iceland whose landscapes seem to exist without relation to (or care for) human agency. The couple experiences the various stages of apocalyptic realization: confusion, panic, welcoming the rapture, acceptance that there is no rapture, hey wait! laws/social norms/money no longer matter — let’s party! You could excerpt parts of this movie as a tourism promotion as these two just wander around beautiful landscapes and the unpeopled streets of Reykjavik.

But eventually it all falls apart. The couple frets about how they will ever get off the island. The geothermal grid starts to fail, water stops flowing. They bicker over the proper order in which to eat expiring food. It’s a dark psychological drama underwritten by a low-grade end-of-the-world vibe. But it’s also in part a morality tale about living in the moment. Eventually our Adam and Eve meet the anti-Job, a guy who is still somehow still alive living in a cabin and determined to give up. He teaches them the Welsh word hera: grief for a home to which you cannot return. I’m not sure there’s anything specifically Icelandic about this emotion, but Iceland certainly makes for a great setting for its exposition.

⅓ of the entire cast of Bokeh is Maika Monroe who made her debut in It Follows. Reddit of course links the two films: “This movie is a sequel to It Follows and the main character, played by the same actor, had sex with someone and then they had sex with someone (and so forth) until everyone died/disappeared. The old man was the last person to go before it was Jenai’s turn. The reason Riley survived was because he never had sex with her as he was waiting for marriage. (Obviously).” And now I want to dream up other unintended sequels linked by mutual actors.

Child Eater (2016)

If you thought the incessant repetition of “This ends now!” and “Evil never dies!” from Halloween Kills was cringey, boy have I got a movie for you. I debated including this one, as it is set (and shot) in the Catskill Mountains of the USA, but its writer and director, Erlingur Thoroddsen, is from Iceland. Child Eater ultimately is part cabin-in-the-woods, part stalker babysitter, with a dash of Jeepers Creepers and A Nightmare on Elm Street — which you might otherwise think was an homage, but this is really just a mess. You see, there’s a gnarled old guy living out in the woods, abducting children, and then eating their eyes in an effort to keep himself from going blind. That’s it. That’s the movie.

Rift (2017)

Not to be confused with The Rift (reviewed on the previous Terror Tourist), this ambitious story of two former lovers centers on the sexual and emotional trauma that characterized their relationship. Amazingly this thoughtful, beautiful, haunting film comes from the same writer-director as Child Eater, Erlingur Thoroddsen — and only a year later. The guy’s got range is what I’m saying. Like most of the other films here, Rift uses the tension between the sublime and the outright terrifying of Iceland’s landscapes metaphorically. Mind the rifts wherever they appear. This film may be too slow for some viewer’s tastes and those who desire firm closure might be disappointed. But it’s worth it just for the two leads’ performances. Maybe make it a double feature with Child Eater just to test the limits of your cinematic taste?

I Remember You (2017)

Probably the most ambitious film in the mix, I Remember You is two intertwined stories, one a mystery of a child lost in the city (naturally Reykjavik), the other a more straightforward tale of haunting at a remote seaside cabin. Some of the fun of it is simply trying to figure out why these two strands are being told in the same filmic container. Your effort will be rewarded in the end, thankfully. Keep your ears open for the wonderful sound design and your eyes peeled for the Exorcist III hospital corridor call-back. Óskar Thór Axelsson, director and co-writer, knows what he’s doing.

Spell (2018)

Here’s Iceland through an American tourist lens. A man, Benny, escapes to the island after the tragic drowning death of his fiancee. Their difficult relationship comes through in flashes throughout the film as a backstory. There are several interesting things about Benny. He has a compulsion to lick things, like surfaces and rocks — pica, sorta — which is only mildly disgusting until he visits the (very real) Icelandic Phallological Museum when it becomes farcically disgusting. Benny is also an unfulfilled illustrator. This matters as a plot point when he meets some Icelanders that want to show him off-the-beaten path sites. Benny’s runic scribblings apparently convince his creepy tour guide that he’s “chosen” (for what we’re not entirely sure). Spell is a movie about grief, dumb Americans in Europe, mourning, mental illness, and superstition. There’s something comfortable about the rhythm of this film. The beat seems to be building to a compelling climax. But the drum kit falls off the riser in the end — which is a shame since the other 90% of this film is very entertaining.

I suppose what I learned on this journey through a small genre from a small island is that Iceland very much does its own thing stylistically. Certainly there are homages and influences from other countries’ film traditions, but every one of the films we just visited have elements that are unique to Iceland’s traditions, location, or circumstances. And the country continues to produce. Recently The Damned, a 19th century shipwreck period fright,premiered at Tribeca. Iceland even has its own, singular horror festival called Frostbiter this year from Nov. 15-16. So if you’re in the area, check that out!

Thank you for traveling with me today. Until our next excursion, may your itineraries be horrific and fulfilling!

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.