Pied-à-Terror

Prefer to listen to this post?

There is no more important location in horror fiction than the house. The geometry of surfaces that creates an inside where only outside once was, subject to the decay of time like a human body, able to be loved, often to be feared: the haunted house. Tourists, as I speak to you now from a home emptied of the people I love and denuded of the artifacts which made it a place of life, I plot today’s itinerary inside an actual haunted house, haunting at least to me, if not by ghosts, then by memory — which may, frankly, be the same thing. Today we explore the horror of the built environment in a segment I call Pied-à-Terror.

Let’s ask a fundamental question as we begin our journey. Why is so much horror fiction set in houses or other built places of living?

Houses are made for people to live in (as opposed to barns for animals or sheds for storage). There’s a sense that when homes aren’t occupied by people they are at best cold and empty, at worst somehow desirous for other things to move in. We have an urge for homes to be populated, usually by people, and if not then reminders or ghosts of people. They are vessels for living and we want to fill them with something. This is why it is demonstrably more difficult to sell a house that has no signs of life at all (no furniture, etc) than one that is.

Historically, most people have died in their own homes, at least since there has been the concept of a home, and usually they’ve passed away inside bedrooms. Even today some terminally ill people choose hospice inside their homes specifically so that life can end there rather than in a hospital. People who have died — by choice or not — in a home are of course the source of the innumerable ghost tales associated with haunted buildings. We anchor people to location probably more intensely than any other correlative other than smell. (You simply can’t beat smell. Thanks, lizard brain!)

Scientists call this the “sensed-presence effect”, the feeling that there is another person present when there is not. This is explained as a result of monotony, darkness, cold, hunger, fatigue, fear, and/or sleep deprivation. All things that happen to people, especially when alone in a house. Other explanations proffered include hypnagogic hallucinations, restless leg syndrome, and of course very often outright hoaxes. Sometimes it’s the actual decay of a building that is to blame. Carbon monoxide, pesticide, and formaldehyde can lead to hallucinations and have at least on a few occasions been documented as the source of perceived hauntings. Clear up the monoxide leak, no more ghosts.

A poll from almost 20 years ago noted that 37% of Americans, 28% of Canadians, and 40% of Britons believed in haunted houses. I bet the numbers are higher now. But haunted houses are one of the oldest beliefs around. Pliny the Younger, the author from first century Athens, wrote what we think is the first tale of a haunted house, in this case a Greek villa bedeviled by a scraggly, bearded man in chains who really just wanted his bones properly interred.

Haunted houses more recently are, of course, everywhere. They are an entertainment industry totally separate from books and movies, especially around Halloween. And their popularity seems to be increasing: I’ve noticed many temporary haunt attractions just staying up and re-theming as Christmas-inspired haunted spaces. Soon it will never not be haunted house season.

Haunted architecture in horror movies specifically fall into a few categories. Let’s walk through this neighborhood together, tourists. Hold hands if necessary.

Our first stop you’ve visited dozens if not hundreds of times before. It is the traditional haunted house (and its inbred cousin the cabin-in-the-woods). If there is a single icon of horror cinema, it is this — the ornate Gothic or Victorian mansion, usually up on a hill, often in a state of disrepair. The formula varies, but, like obscenity, you know it when you see it: Norman Bates’ house in Psycho, the neoclassical mansion from both Phantasm and Burnt Offerings, the haunted house on a hill in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, New England’s iconic The House by the Cemetery (1981), even the Art Deco castle of the pre-Code blockbuster The Black Cat (1934) — the list is effectively endless. All manner of bad things happen in these houses which are really just dressing on a corpse.

Tourists, let’s take a quick peek down this side street before we get to the next stop. Often what I have called traditional haunted houses are simply creepy locations for the purpose of mood-setting; the threat is something inside (like ghosts) or outside (like home invaders). But sometimes it is the building itself that is the malevolence. Think of the house at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, NY (not to mention that its facade actually looks like a menacing face) or The Overlook Hotel in Kubrick’s take on The Shining, or the outpost dormitory of Robert Eggers’ 2019 The Lighthouse. All of these structures are the antagonists, even while they possess or animate otherwise good people to do very bad things. Put another way, the houses are the source of the misbehavior rather than just the setting for it. This was the twist in Insidious (2010): where all the signs pointed to the home being evil we’re told quite explicitly “It’s not the house that’s haunted”.

One last excursion in this neighborhood if you will: we’re entering the cul-de-sac of suburban horror. The houses in these locales are not exactly terrifying, but their location — in seemingly cozy, safe subdivisions — and their very un-exceptionalism make the horrors they contain that much more disquieting. You probably don’t live in a decrepit castle, but you have at least been in a residential neighborhood. The message in these movies is that the crazy person with the machete will get you either way. Sometimes the very sameness of the homes of suburbia is the scare. Take Vivarium (2019) about a couple who cannot escape — as in, literally cannot find their way out of — the monotony of identical townhouses that make up their community. Poltergeist (1982) was one of the first movies to foreground suburbia as, if not the villain exactly, at least the problem. Developers intent on turning rural land into a planned community place a new home directly above a cemetery, moving only the headstones. It’s a deliberate commentary on suburbia as Steven, the Dad played by Craig T. Nelson, is a real estate agent. Even the original Halloween (1978), set in the fictional community of Haddonfield, places the killer on leafy sidewalks of what would otherwise be the most non-threatening of neighborhoods. In a nod to tradition (maybe), Carpenter used a folk version of a Victorian house for the Strode residence. Suburban homes became such a trend for a while (A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Gate, and countless others) that the first full-throated meta-horror, Scream (1996), was set precisely there.

Our next neighborhood, my tourists, is known for its surreal architecture. Sometimes these Escher-esque places are inhabited by ghosts or monsters, but in all these stories the frightening core — and often the thing that kills — is their spatial disorientation. I have personal experience in this regard. The first office building I worked in, called Wildwood Plaza in Atlanta, was designed by renowned architect I.M. Pei and opened just two years after his pyramid entrance to The Louvre debuted. Like any young idiot new to office culture I could not find my way around, but I later learned this was by design. Pei loved messing with right angles, which is to say, not having them. The halls, ceilings, and many rooms of Wildwood Plaza lacked traditional 90° joints between planes. It was wildly, though not always consciously, confounding. As right angles do not exist in nature, except accidentally, humans have come to rely on them to create orderly, understandable, legible spaces. And when that convenience is missing, we get confused or feel trapped. Which is why illogical or impossible spaces are so prevalent in horror. When characters are disoriented, so are we the viewers.

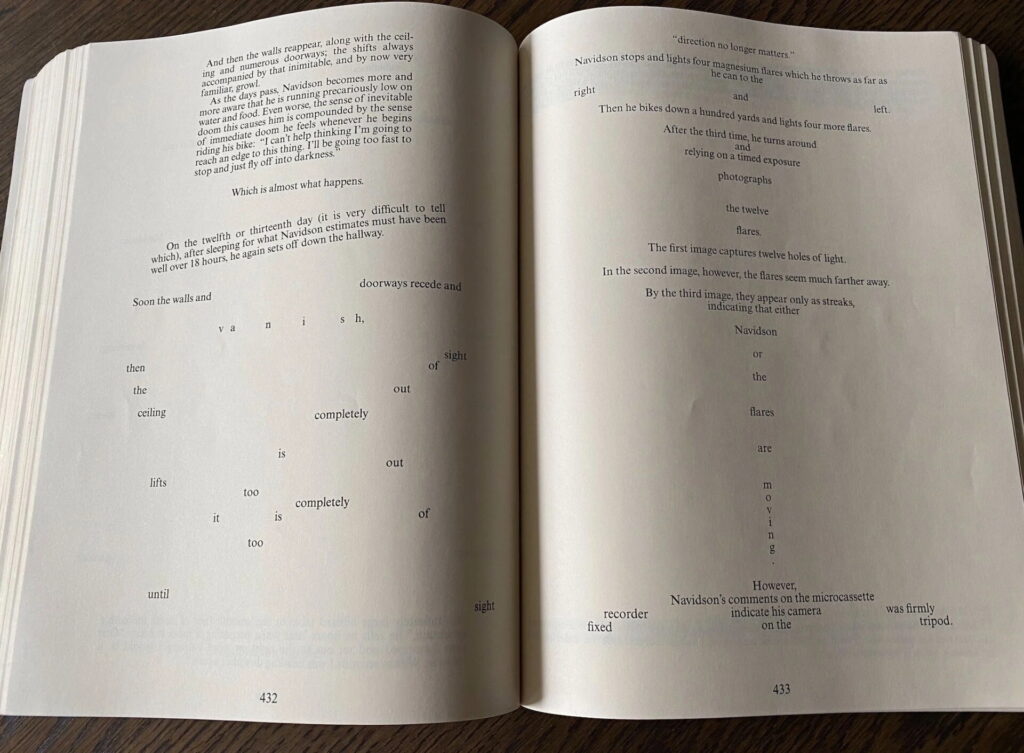

The touchstone of this genre has got to be the book House of Leaves (2000) by Mark Z. Danielewski. To say that House of Leaves is a story-within-a-story is to leave out at least a half-dozen nested stories. But, at root, is a documentary film purporting to show the lives of a family as captured by their in-home camera system. Their house begins to change in very non-Euclidean ways — doors appear were once only walls stood, corridors extend impossibly beyond the house’s exterior envelope, a gigantic seemingly endlessly-descending spiral staircase appears inside a maze at the end of a hallway. The thing about this book, though, is that the writing style and format are simultaneously metafictional, with multiple narrators at cross-purposes, dozens of different typefaces and colors in use, and even pages that require physically rotating the book or reading it reflected in a mirror — all of this is the house-as-maze-like book or maze-like house-as-book. They are both haunted.

Danielewski’s novel has never been made into a film. I’m not sure it could be. But hoo boy would I watch it if it were. (Sidenote for game nerds: there is a Doom mod called MyHouse which was purported to have been created from a simple house map that the creator’s friend, recently deceased, left on a floppy drive. It is very much not that as the house shifts its shape and orientations, just like House of Leaves.)

Cube (1997) is a perfect example of, if not strictly-impossible, then highly improbable architectural horror. It follows five people who find themselves in perfectly square rooms that containing numbered hatches on the floor, the ceiling, and every wall which lead to exactly similar rooms, though each has been separately set with deadly traps. By way of prime number mathematics and, helpfully, learning that one of their cohort was hired to design the outermost shell of the maze, the group devises a plan of escape only to learn that, in fact, the structure is more of a Rubik’s Cube than a static one. The rooms can reconfigure and attach to different rooms. Like the rooms themselves, the movie Cube has led to three other near-duplicates of itself Cube 2: Hypercube, Cube Zero, and a Japanese remake.

Other good examples in this sub-genre include The Platform from 2019 about a vertical prison whose inhabitants are fed by a giant dumbwaiter that drops daily from the topmost floor through 333 levels, leaving the lowermost with nothing but crumbs and gristle, Relic, an Australian film from 2020, where the house of an elderly widow comes to mimic her own dementia, and even to some degree the haunted hotel room film from the Stephen King short story 1408.

Tourists, let’s end our walking tour at some places that deserve special attention. Here are two films that stand out precisely because they are about architecture per se.

The Night House (2020) begins with Beth whose husband, an architect who designed and built the house she lives in, has just committed suicide. One of her friends consoles her saying “You spend so much time with in the same space with someone it’s gonna feel like they are there even when they are not.” If you’re looking for the TL;DR version of this essay on haunted houses, that quote is it. As Beth attempts to deal with her grief she suffers from what seem like hallucinations until she stumbles upon a set of floorpans for a reversed version of her house. Eventually deep in the woods she finds an actual reversed copy of her house filled with ghostly women who look similar to but not exactly like herself.

This film makes great use of literal architecture as the source of fright. There’s a scene where Beth notices that the shadows cast by the moulding atop a basement pillar look unsettlingly like a human silhouette. It’s so clever and well-executed that I missed it, until the shadow moves and I jumped out of my seat. Without spoiling the movie I will say that Owen’s construction of a house-in-reverse is an attempt to fool dark forces out to get Beth who seems to have thwarted their plan for her years ago. The crazy house is actually the solution to the haunting rather than the haunting itself. A very novel take on the trope indeed.

Written and directed by Lars Von Trier and starring Matt Dillon, The House That Jack Built (2018) is a story that hangs off the scaffolding of the structure of Dante’s Inferno. It’s told through a series of flashbacks to the murders of Jack, a wannabe architect and very definite serial killer. The movie contains a narrated dialogue between Jack and Verge (obviously Virgil from Dante) as he descends through his crimes and the nine levels of hell. At one point Jack says “The old cathedrals often have sublime artworks hidden away in the darkest corners for only God to see or whatever. One feels like calling [him] the great architect behind it all. The same goes for murder.”

Throughout the film we’re shown Jack attempting to build his own house from scratch, becoming dissatisfied with his progress, bulldozing it, and starting anew. Meanwhile he’s still killing, often disgustingly so. The movie’s climax takes place in the freezer where he keeps all the corpses of his victims. Verge appears, no longer just an overdubbed narrator, and reminds Jack that he’s never been able to complete his house between all the murders. So, improvising, he arranges all the dead bodies into the shape of a house. It’s a very disturbing image. Jack and Verge enter the house and drop down through a hole in the floor just as police are cutting their way into the freezer. I won’t spoil the epilogue, but if you know Dante you know how this ends. Ironically it is the failure of architecture — in this case a collapsed bridge across the River Styx — that plays a fateful role for Jack.

Of note, this is very long for a horror movie. Over 2.5 hours. Probably could have used a heavy-handed editor and would have been a fine flick without the Inferno metatext and frequent digressions into William Blake, Albert Speer, and others, but I don’t fault its ambition and it does not bore. Of note, there’s brief but very hard-to-watch animal cruelty in one flashback. (It’s CGI, but still.)

A poll from a few years ago found that 64% of people surveyed prefer to watch horror at home rather than in a theater. For movies of all genres the percentage of people who prefer to watch at home drops to 55%. Of course the theater is a different experience entirely (immersive visuals, superior sound, communal experience), but maybe the 9% point difference is meaningful. Maybe there’s something about being scared in the comfort and safety of your house which adds to the allure of horror movies. Is it possible that for that 90 minutes we enjoy living in our very own haunted house?

OK tourists, I hope you enjoyed our excursion today. Time to go home. May I suggest putting on a scary movie?

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Pied-à-Terror”: