Garden of Forking Paths

Prefer to listen to this post?

My traveling compatriots, I know it has been a wearying year of sites and topics, but we can’t let up now. We’re gonna get super lost today. Maps won’t work. Itineraries will be an illogical mess. Today we’re gonna talk about non-linear horror in a segment called The Garden of Forking Paths.

The shortest path is a straight line, right? Probably, if we forget about bizarre quantum behavior and wormholes, but sometimes a line that isn’t straight at all can make for an interesting story. It’s true that the constraints of film — which are produced by someone (or group of someones) controlling the progression of a story which has a discrete beginning and end — make non-linearity difficult and sometimes confusing. Moreover the format of film basically disallows choice or meaningful interactivity from the viewer. But this difficulty, this resistance in the materials so to say, can deliver compelling and often unsettling films. Non-linear storytelling is most common in thrillers and to some extent drama, but it’s the very way that going against convention destabilizes the viewer that makes it perfect for horror, when done well.

The title of our journey today, Garden of Forking Paths, refers to a 1941 short story by Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges (full text here) in which he describes a writer who has created an infinite text which forks off a new story from every single event in his novel. While we don’t have that (in any form of fiction) the internet has, in a way, given us a garden of forking stories, however amateur, in the terabytes of fan-fiction that are spun up extending beloved or cult novels and films. This doesn’t happen as much in horror as in other genres, though it certainly does happen — even sometimes convincing studios to make actual films based on fan concoctions and hoped-for franchise crossovers. Or sometimes fans just take it upon themselves, copyright be damned, to make films out of stories they dream up. For example, the surprisingly good Never Hike Alone, is one of 19 fan-made films listed for Friday the 13th on IMDB. (I struggle and fail not to mention the largely fan-driven Amityville universe, which at the time of this recording, consists of 56 films. This may be the closest we’ll ever get to Borges’ garden, sadly.) The horror-adjacent genre of true crime also spins out dozens of potential storylines by virtue of the fact that these shows often do not have an ending, some of which like Unsolved Mysteries come right out and tell the viewer so. Everyone watching these shows has a theory and amateur sleuths set off on sometimes ludicrous attempts to provide their own narrative conclusion.

But these are all exceptions to traditional filmmaking and you could argue are examples of derivation rather than non-linearity. So what about actual non-linear horror films? OK, travelers, fine, let’s get back on the path — but I told you I’d lose you. The irony is that most films are not shot in a chronological sequence that conforms to time as depicted in the movie. This of course is for logistical, often economic reasons. But my guess is that some directors — in shooting out-of-sequence — are presented with new artistic possibilities of contrast, juxtaposition, or information disclosure that weren’t in the script to begin with. This is just a personal theory. Any listeners out there who direct films, please tell me how wrong I am.

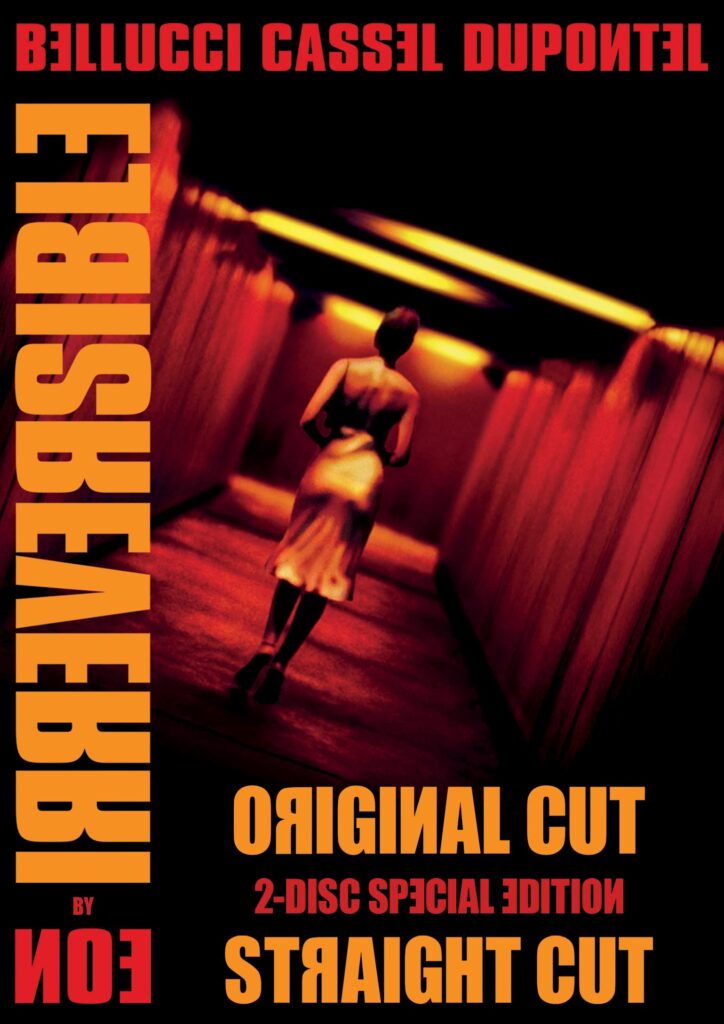

The simplest kind of non-linearity are flashbacks and rewinds. Many horror films contain at least a bit of storytelling purely for backstory purposes. When this is done anywhere but the beginning of the film that’s a flashback. There are too many examples of this to list, but some films use flashback in novel ways. The original Cloverfield, a kind of modern-day Godzilla flick, is presented as the continuous footage from a camcorder the night of the film’s mayhem. The expository flashbacks occur in sequence, though, as they are snippets of home movies previously recorded on the tape that is being recorded over imperfectly the night of the events of the film. It’s quite clever. Many of the Saw franchise, certainly the first, only make sense once the chronological events of the film are decoded via an elaborate narrated flashback at the end of the film. This flashback is a kind of storytelling in reverse, an actual rewind re-interpreting the events you just witnessed through a different frame. The 2002 French film Irréversible by Gaspar Noé presents an entire film in reverse, which of course inverts the audience’s normal sense-making task and expectations. The film follows two men attempting to avenge the rape and beating of the woman they love. It is also one of the most graphically brutal films I’ve ever seen. Two versions of this film exist. The original at 97 minutes and the “straight cut” told in forward chronology at 86 minutes. Having not seen the straight cut I don’t know which 11 minutes were cut out, but it does make me wonder if they contain plot points that are only necessary to avoid complete confusion in the original, reversed telling.

Moving into more complex non-linearity are time travel and time loop-based horror films. Listeners need only loop back one episode in their podcast queue to last week’s Heavy Leather Horror Show for a good example of a horror time loop (played out literally as spatial recursion) in the film Drive Back. Time loops work especially well in comedy and horror, related genres in so many ways, because they give the audience the opportunity to wonder how the next iteration will deviate from the previous. This is a setup for a laugh (in the case of comedy) or a surprise (in the case of horror). Time loopy horror, though, benefits from the very claustrophobia of the conceit. Being trapped in time is no less scary than being trapped in a space. Scarier, in some ways, because at least characters can die trapped in a space; often in time loop tales they can’t even perish, trapped forever in a looping hell of the same events over and over. Another good example in this sub-genre is the film Every Time I Die, “the story of a man, who after being murdered, finds his consciousness transferred to the bodies of his friends and tries to warn and protect them from the killer who previously murdered him at a remote lake.”

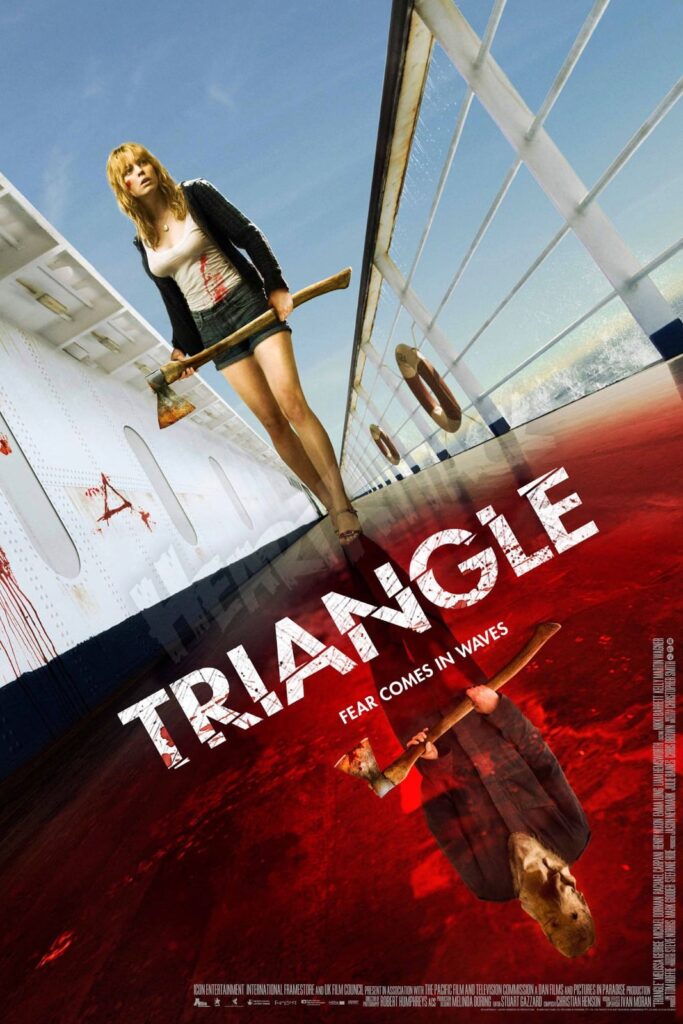

This week I watched Triangle a 2009 British piece of non-linear horror that really leans into the intrinsic terror of being caught in a loop which becomes a downward spiral as the realization of helplessness sets in. A single mom named Jess, played by Melissa George, with a fraught relationship with her young autistic son decides reluctantly to go on a sailboat excursion with friends. The boat is capsized by a freak storm and they all cling to its hull until an ocean liner with a single figure on its deck comes by. They board it and things start getting weird. For one, it’s empty except for a hooded figure trying to kill them all with a shotgun. Clocks are not in synch. Everything seems strangely from the 1920s. Eventually Jess figures out it is herself — or a version of herself — with the hood and shotgun and that she’s in a horrible loop. She does eventually escape the boat-based loop only to find that she is in another, more terrifying one. This isn’t a scary movie or a gory movie, but it is psychologically harrowing, especially at the end. Or rather, especially when the movie stops.

The majority of non-linear horror is more difficult to classify. There’s no accepted term for the kind of psychological horror whose narrative logic seems pulled straight from dreams. Let’s call these dreamtime films. Psychedelic, nested, or often completely illogical, these films are more about how they make viewers feel rather than providing a coherent narrative. This is non-linearity not as a storytelling device but as a mood-setting technique. What impressionism is to realism in painting. And it works so well in horror. Just the break with convention can be upsetting to a viewer, forget about jump-scares or blood (though they contain those too, of course). Examples of dream-like non-linearity include: Climax (an even more fucked-up film by Gaspar Noé), In The Mouth of Madness, Jacob’s Ladder, Annihilation, Possession, and Videodrome.

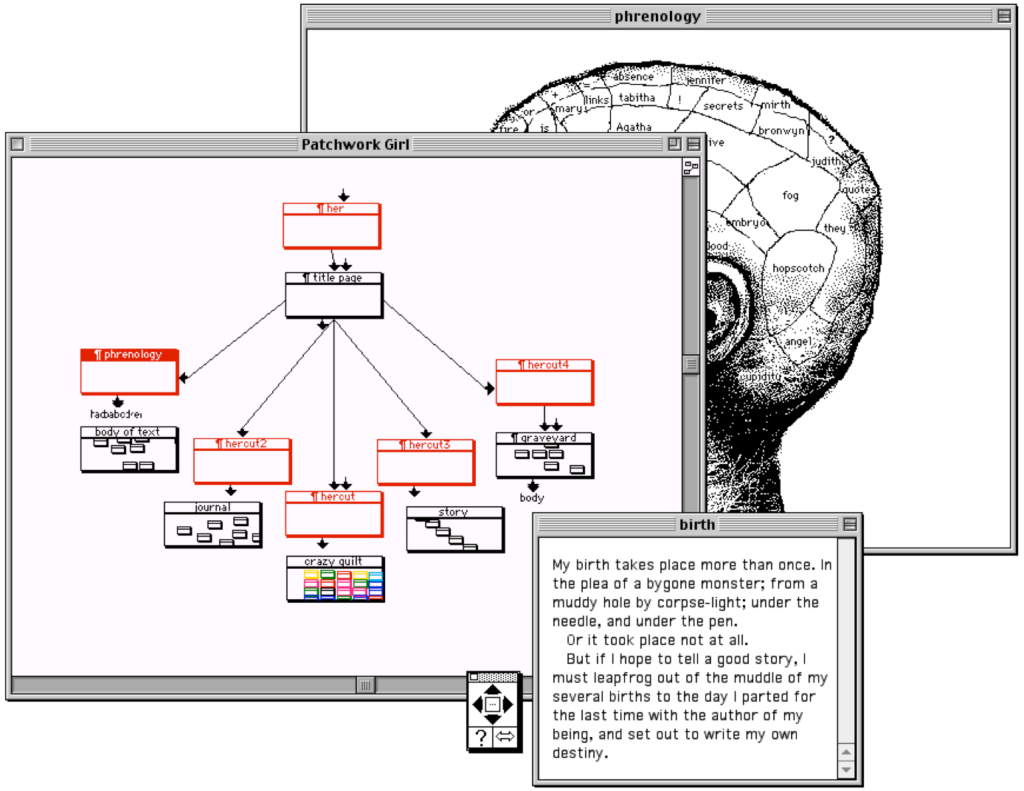

Travelers, let’s stay with horror but step just off the path of film for a moment to talk about true non-linearity, which is to say, interactive storytelling. If you are of a certain age you surely remember the book series from the 80s called Choose Your Own Adventure. These books were presented as literal forking paths where readers would decide what the protagonist should do at various decision points. They were fun, though of course they were finite — an example of what literary theorists call interactive multi-cursal (that is, many paths) storytelling. The reader’s agency was limited of course: go to this page or that page based on a fairly binary choice (i.e., “pick up the hammer” or “pick up the milk carton”). Some of the stories in the original Choose Your Own Adventure were horror tales (like “House of Danger”, “Vampire Express”, and “Ghost Hunter”) and there was even a 90s knockoff called Choose Your Own Nightmare. The niche electronic literature genre known as hypertext has few classics but one of them has to be Shelley Jackson’s 1995 Patchwork Girl, a re-telling of the Frankenstein tale. It’s so much more than that though: what seems like disarticulated scraps of text eventually comes alive, stitched together like the original monster. Being computer-based, Patchwork Girl has sophisticated mechanisms in place for allowing you to continue reading along paths only if certain passages have already been read (or not read). I highly recommend seeking this out. It’s on the platform called Storyspace.

But really interactive horror that would actually frighten someone (and which gave more than yes/no decision-making opportunities) had to wait until video games in the early 2000s. Classic survival horror like Resident Evil pioneered the genre, which would reach its full maturity in titles/franchises such as Silent Hill, House of Ashes, Until Dawn and my personal favorite Dead Space. Indeed many video games today use the same techniques as film — real-world sets containing actors in motion capture suits for instance. And the graphical capabilities of today’s machines make verisimilitude the norm but of course never a constraint.

The question often asked is: can you be truly scared when you’re in control of what happens? My answer is absolutely yes, indeed I am sometimes more frightened playing a horror game than when watching a film. Being disemboweled as a consequence of your own actions is a lot worse, for me, than simply watching someone on the screen dump their guts on the floor. I would even say that I have seen horror gaming as a gateway experience for people who would otherwise never watch a horror movie. The sense of control was enough to get them to play a game but then, having enjoyed it, they sought out horror films.

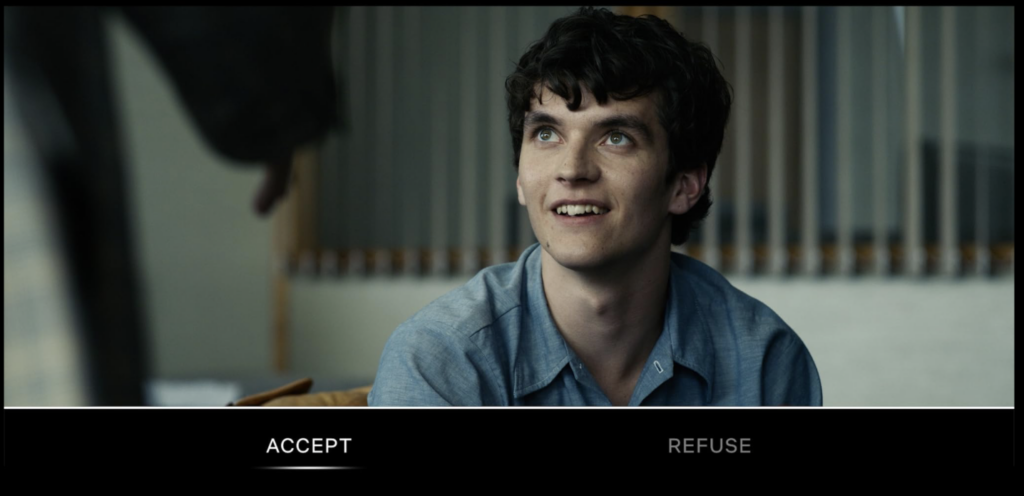

The viewer-in-control aspect of video gaming has even wandered back into film. The 2018 Black Mirror episode called Bandersnatch required new functionality to be built for the Netflix player. The story follows — or at least begins with — a software developer trying to get a game published. You, as viewer, determine the choices he makes. It’s just the right balance of sit-back enjoyment and lean-forward engagement for my taste. The runtime says it is 90 minutes long which may be what happens if you make no choices at all (after 10 seconds the story continues along some default path), but to view everything would take 312 minutes. The shortest possible path to a point called an end is 40 minutes. It’s all live action and, being Black Mirror, quite dark. I do not think Netflix has done anything further with this functionality, but I wish they would.

Previously on this show I have plugged a phone app called Guide Along. It’s meant to tell you about things you are seeing on road trips, often but not always through national parks or exceptionally scenic drives. The key to this app is that the story segments are entirely GPS-based. Wherever you are it tailors the content, even reminding you to drive the speed limit lest you trigger a new story too soon. This is non-linear storytelling too, of course, where it isn’t the viewer’s decisions so much as their literal location that determines the sequence. I don’t think there’s an application for this in horror filmmaking, though there could be in haunted house attractions. If you are an investor and this idea appeals to you please call our hotline at (724) 246-4669.

Well that’s it, travelers. Hope you weren’t too flummoxed by today’s journey. Actually If you’re not confused I did this wrong and I recommend you watch any of the films mentioned here. Until next time, whichever timeline that is!

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Garden of Forking Paths”: