A Trip Down Witch Lane

Prefer to listen to this post?

Good evening, fellow travelers! Dust off those walking shoes or mount your beast of burden because on this journey we’re traveling down a single road. It’s a relatively lengthy one, though, and it has many ups and downs, twists and turns. Today we are taking a trip down Witch Lane.

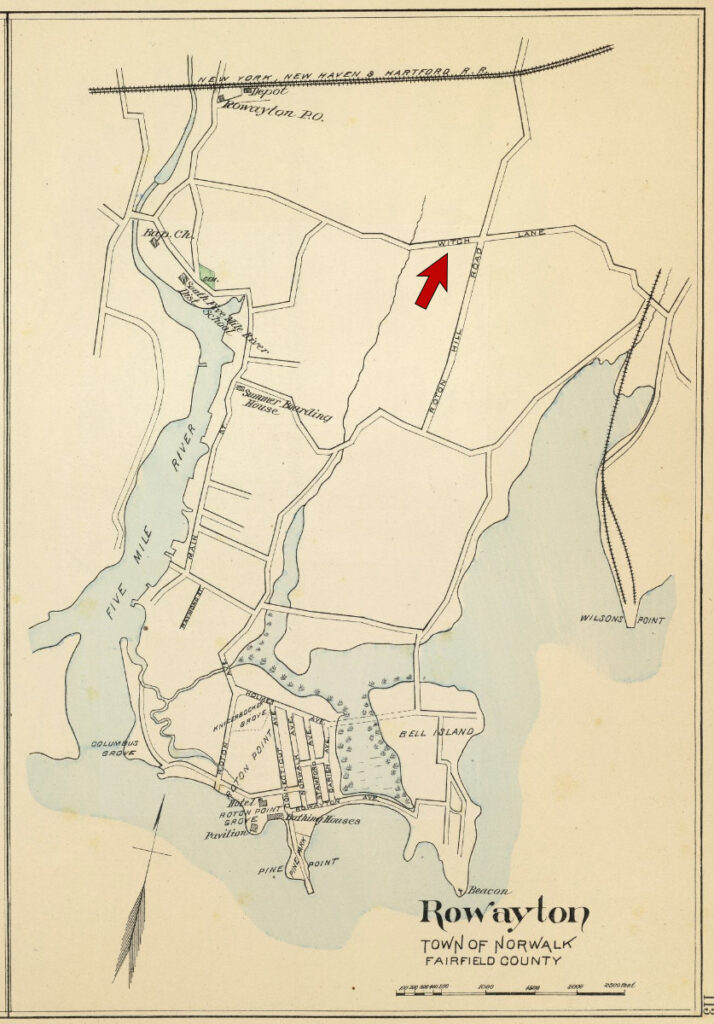

Like all good excursions this one may say as much about the tour guide as it does the locale. You see, in a few days my wife and I will own a home on a road called Witch Lane located in the Norwalk, Connecticut village of Rowayton. This is not in itself all that novel. There are dozens of place names on the east coast named for witches: Witch Path in West Springfield, MA; Witchtrot Road in South Berwick, ME; Witchduck Road in Virginia Beach, Virginia, Witches’ Rock Road in Bristol, CT, and so on.

It is also, of course, coincidence that I am about to live on Witch Lane and I am a member of the number one horror podcast out of Salem, Massachusetts, a town globally known for its association with accusations of witchcraft. Or is it a coincidence? Let’s explore.

I like to know a bit about the places that I live, so, being a naive new transplant to the region, one of my first educational stops was the local historical society. Run out of one of the oldest and arguably most scenic old homes on the Rowayton waterfront, the historic association is the keeper of archives, photos, artifacts and memorabilia of this coastal community. I knocked on the door and was greeted by a group of older ladies, most of whom were holding brooms. This is not a joke, travelers, for it was spring cleaning day at the historical society. I explained that I was new in town, about to move to Witch Lane, and that I was curious about the place name etymology. (Word nerd sidebar. There is a term for place name etymology: toponymy.)

Surely these ladies would know something about a lane named Witch in a town full of roads and parks named mostly after Native Americans and prominent early settlers. But no. “No one knows,” they said, straight-faced. I could not believe this. And they added that no one seems to know why there’s a small forested area called Devils Garden either. I said “Witch Lane literally becomes Hunt Street a little way down from our house. Can this possibly be unrelated to, you know, witch hunts?” Blank stares from the ladies. As it happened the former town fire marshal was in the building at the time so I asked him too. Nope, nothing, no idea. Now, I understand that not everyone is as interested in the bizarre and the horrific as I am, but shouldn’t a historical society at least have an inkling about a place name like Witch Lane, especially in a state still reckoning with its legacy of witch accusations?

And then I had a thought: maybe feigning ignorance is precisely what a group of broom-wielding ladies (dare I say, a coven) would do. They are entrusted with safeguarding the village lore. Maybe they don’t just willingly give that information to an outsider who comes knocking. Or maybe they knew I would come asking, which is why the fire marshal was there. You see, the home we are about to move into is not the original house on the lot. The former building there burnt to the ground in 2014. I had contacted the current fire marshal to inquire about this and his response was that the cause of the fire was never determined but that it consumed the entire structure and caused no loss of life. The owners, however, did not stay. Could it also be coincidence that the former fire marshal was also in the room when I stopped in? Perhaps they had a plan all along to deal with me, the nosey newcomer.

Now, if this sounds like the plot of one of the many films we’ve reviewed on the Heavy Leather Horror Show you would not be wrong. And this would be the part of the movie — almost a cliche in much of horror — where I take matters into my own hands and fall down a research rabbit hole. Cue the scene where I visit the local library (which I did), images flitting by on a microfilm machine (have not done that yet), and video calls with an elderly professor of the occult (which I will do if I have to). Here’s what I have learned.

Of the six or so books I read on Rowayton only one contained any mention of Witch Lane’s name derivation — and that was in an appendix I almost missed. It notes that Witch Lane is one of the area’s earliest named roads. Indeed, as late as the mid-19th century it is really only one of three roads depicted on the oldest extant map we have of the area. But then the appendix says two interesting things:

Said to be named for some women residents speaking a strange tongue.”

A dozen French speaking Arcadians were billeted in Norwalk during the French and Indian War 1759. Some may have remained and thought to be witches.”

Let’s take these separately as I am not sure they are necessarily related.

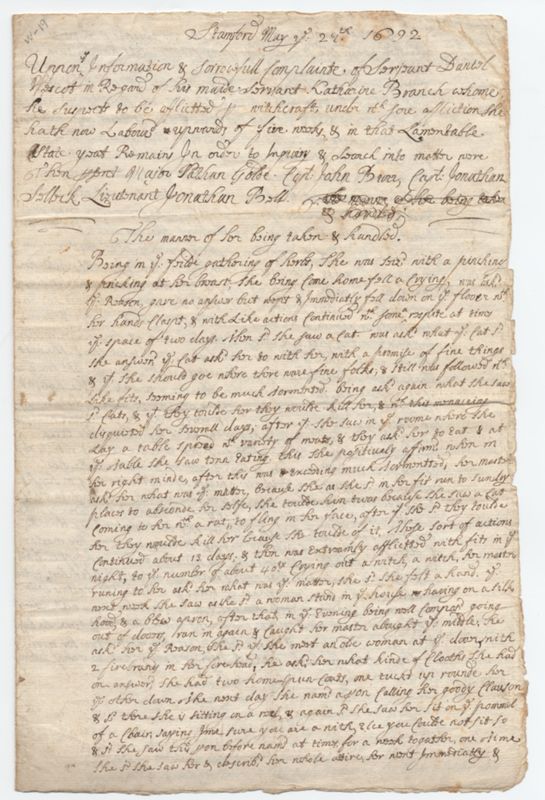

The first — “Said to be named for some women residents speaking a strange tongue” — seems plausible. The first witch execution in the colony of Connecticut was in 1647, kicking off a period of hysteria that lasted almost two decades. Norwalk — the larger city to which Rowayton belongs — was founded in 1651, right in the middle of this panic. Most people have of course heard of the Salem witch trials, whether from numerous TV shows and movies, the play The Crucible, or simply from the way it is seeped into everyday language with the term “witch hunt”. But Connecticut’s collective delusion much predates Salem’s and on a percentage basis of accused-to-executed was far deadlier. Accusations of witchcraft in Connecticut flared up continually culminating in the nearby Stamford witch trial in 1692, contemporaneous with the mayhem up in Danvers. Fair to say that a fear of sorcery — or at least fear of people acting oddly — was in the water here. It does not defy belief that people, especially women, speaking a strange tongue would be othered at best, thought to be witches at worst.

There’s a problem with this theory, though. The first settlers in this particular area, what would come to be known as Rowayton, are not known to have arrived until 1740, well after the witch craze had subsided. (The last witch execution here happened in 1697.) And this is where the second sentence possibly offers some insight: “A dozen French speaking Arcadians were billeted in Norwalk during the French and Indian War 1759. Some may have remained and thought to be witches.” Now, there are two possibly sloppy things about this statement. The first is that the author here is clearly referring to Acadians not Arcadians. And the second is the odd verb “billeted”. To explain this let’s take a fork in the road briefly for a quick refresher on colonial American history, my compatriots. The French and Indian War — a conflict between the empires of England and France waged worldwide as the Seven Years’ War — took place on our continent from 1754 to 1763. In so many ways it set the stage for the colonial revolutionary war and independence that followed, but that’s not a discussion for today.

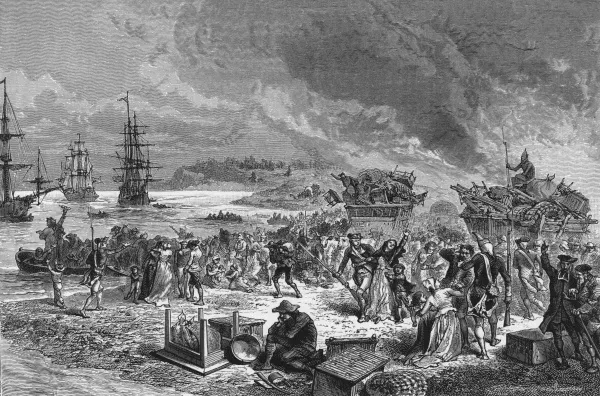

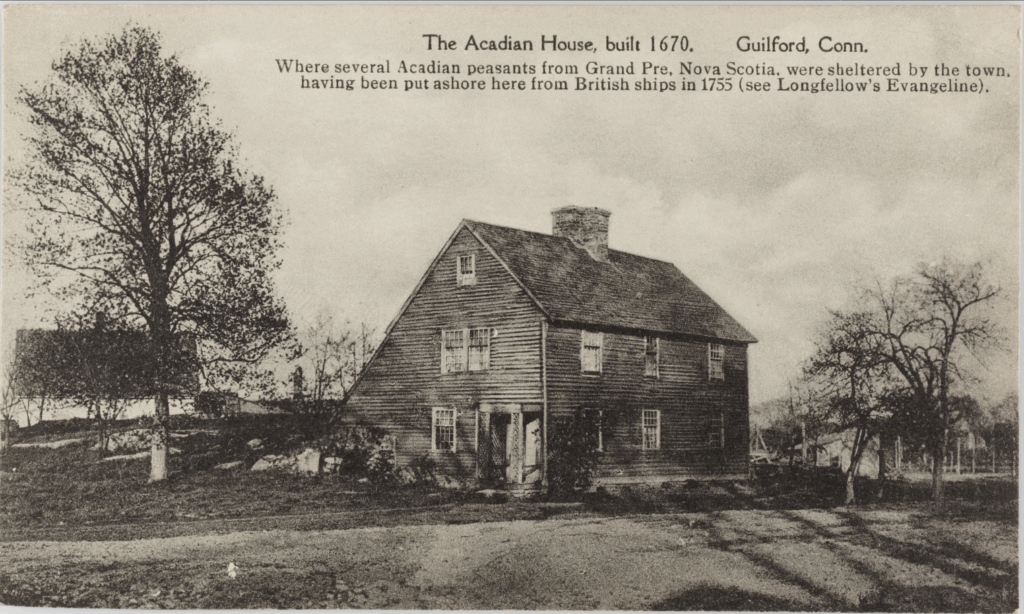

Of note here is something known as the Expulsion of the Acadians or, more eloquently in French, The Grand Dérangement. Starting in 1755 British troops in the Canadian maritime provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, etc) became worried about the Acadian peoples, ethnically French descendants of the earliest French families to inhabit North America. Acadians had a distinct culture, developed over the century prior via frequent intermarriage and cultural transference with the local Mi’kmaq indigenous peoples. But their language was French and, though officially neutral in the conflict between England and France, they were thought to be a threat and so were expelled en masse from their homeland by the British occupying forces. Early on in the expulsion most were sent to the American colonies. (Later, thousands also landed in the French-speaking region of Louisiana. The Acadiens became the cajuns.) So, yes, there were Acadian refugees scattered all throughout New England. They would have spoken French — indeed a variation on traditional French with distinct phonology, accents, and grammar. Even colonial Americans familiar with the French language would have considered this tongue strange. The dispersal of Acadians happened precisely during the founding of — and potential road-creation within — the new town of Rowayton, where Witch Lane now runs.

But that word, “billeted”. Typically this refers to soldiers commandeering a civilian house or building. History nerds will recall that the Third Amendment of the US Constitution disallows this explicitly, at least during “time of peace”. But the Constitution uses the more specific term “quartered”, not “billeted”. In either case why would French Acadians kicked out of their homes by the occupying British be considered soldiers at all? Surely they were not fighting for the French. Connecticut was not an active theater at all during the French and Indian War and even if it were everyone there was either British or a British-supporting American colonist. Hardly the place the enemy would “billet”. But there’s another possibility. Maybe they were actually turncoat soldiers who fought for the British and their new home. Yes they were forcibly removed from their land by the British, but maybe — being officially neutral in the first place — they just wanted to fight for their new home. There’s also the possibility that “billet” was just a poor choice of words and that these were mere refugees. Whatever their motivation or political allegiance (and especially as degenerate papists) these were Acadians … and they talked funny. And we all know what funny talk could lead to in god-fearing colonial New England: accusations of witchcraft!

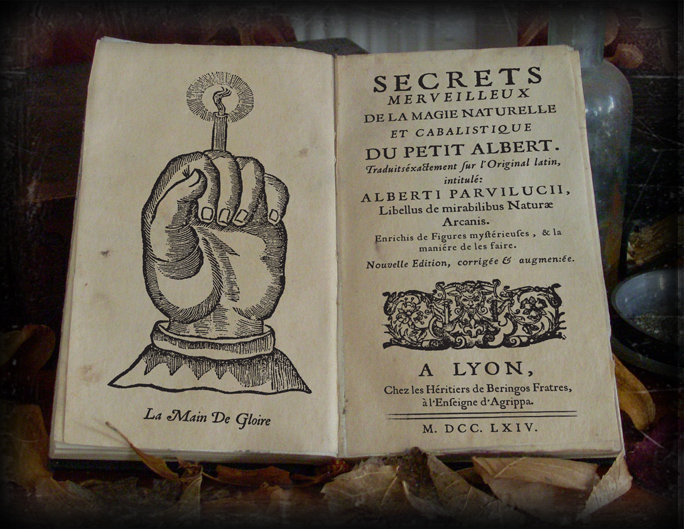

But there’s one last possibility here, as tantalizing as it is less likely. What if the early residents for whom Witch Lane is named were actually practicing witchcraft? What would that even look like? Like other continental forms of folk magic French witchcraft can be traced back through the Middle Ages. People thought to be witches — or who would very rarely self-identify as such — were often healers, cunning folk, midwives, or simply those practicing pre-Christian rituals inherited from their ancestors. French witchcraft is often associated with the grimoire, or book of spells, that witches were thought to carry. The books themselves were real enough, being the first widespread documentation of demonology. (Possibly most well-known is the Petit Albert, a collection of spells and curses for sexual desire, agricultural yield, cooking recipes, and other life hacks.) Often possession of a grimoire was all that was needed to convict someone of heresy and execute them as a witch. Acadians, being originally French, would have brought this European cultural history of witchcraft with them to the New World.

Specifically Acadian witchcraft is not well-studied, but what we do know is that it evolved into a hybrid of European spell-casting traditions and indigenous Mi’kmaq sorcery. The Mi’kmaq, obviously not Christian, revered their shamans for their ability to control the natural world. And the Acadians, being just as prejudicial as other Europeans, would surely have believed these strange-talking others to be capable of witchcraft. Eventually the two traditions merged into a distinctly Acadian set of folk magic beliefs. Is it possible practitioners of Acadian folk magic landed in coastal Connecticut and had a road named after them? Certainly. Is it more likely named for people thought to be evil when in fact they were simply different? Probably.

More importantly, have I, your tour guide and narrator, unwittingly stumbled into a multi-part television series where I am the hapless outsider soon to be sacrificed by the town elders? Will my house be burnt down for my insolence? Or will I instead be welcomed into the local coven of historians? Only time will tell.

There are of course scads of movies about witches set in New England. It’s a cherished American art form. Harder to find are specifically French witch movies (I recommend The Witch from 1906 and Hood Witch from 2023), even fewer Canadian witch movies (I recommend Pyewacket from 2017 and The Curse of Audrey Earnshaw from 2020), and precisely zero Acadian witch movies. (Though there is a children’s novel called The Witch of Acadia. I have not yet read it.) There are a few cajun sorcery movie — I recommend Eve’s Bayou from 1997 — though the degree to which these reflect Acadian beliefs unmixed with voodoo is difficult to disentangle.

But let me at least offer a personal selection of some of my favorite specifically New England-based witch movies, in no particular order:

The City of the Dead (aka Horror Hotel, 1960) — Because Christopher Lee was more versatile than simply starring in vampire movies. Clearly a Salem allegory this one is set in a fictional Massachusetts town in 1692 where a witch named Elizabeth Selwyn is burned at the stake. (Sidenote: no person accused of witchcraft in the United States was ever burnt at the stake. They were all hanged. Witch-burning was an exclusively European thing, and mostly in the medieval period.) Cut to present day and a curious history student takes the advice of her professor (played by Lee) and heads to The Raven’s Inn to learn more about the legends of witchcraft. Guess who’s not really dead? And guess whose side the professor is on. You should watch this movie and you should love it.

Lords of Salem (2012) — Some call this Rob Zombie’s best. I disagree, but it is a good film despite Sheri Moon Zombie being in it. Set in present day Salem, Massachusetts Heidi is a radio DJ who receives a wooden box containing an album by a band called The Lords. She eventually plays it and causes all the women in Salem to enter a trance. This music, you see, was written in the 17th century to control womenfolk. As they say, if it’s nice play it twice.

The VVitch (2015) — Robert Eggers, Anya Taylor-Joy, and Ralph Ineson at their finest. The depressingly hardscrabble rural life depicted in this film influenced my conception of what it must have been like for the early settlers in Rowayton. When the natural world is fully antagonistic it’s easy to understand why the supernatural, for good or for evil, becomes believable. Damn ye, Black Phillip.

The Autopsy of Jane Doe (2016) — One of my favorites, set in the present day, this is the tale of a father-son team of forensic pathologists who must figure out what’s going on with the incorrupt corpse of a 17th century witch. Great use of confined space, a haunted radio, little bells on cadaver toes, and an acting performance that should have won awards from Olwen Kelly who does nothing but lay on the autopsy slab and sheet off spine-chilling vibes.

Mass Hysteria (2019) — Of course there’s a horror comedy based on modern day Salem witch trial cosplay. Is that any more ridiculous than accepting “spectral evidence” — just made-up tales of ghosts — as legally-admissible evidence in the original witch trials? No and it is a lot funnier. This is a short film which overcomes its low budget. Absolutely worth it for the New England witch film completist.

Hellbender (2021) — Technically this is set in upstate New York. (You may argue about whether that is New England elsewhere.) This, though, may be the Adams Family’s best work. It’s certainly their most self-contained in that it was the foursome’s family quarantine project during Covid. Obviously a tale of witchcraft, but more than that it’s about overprotective parenting and why sometimes teenage rebellion has dark consequences.

Well that about does it on our trip down Witch Lane. Obviously witchery is a deep vein to mine, so perhaps we will return to it on a different itinerary. Or maybe this is the last from The Terror Tourist, as the next time this segment comes around I will be a resident of said Witch Lane. And who knows what that will bring? Until then or until never again, I remain, you faithful tour guide.

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “A Trip Down Witch Lane”: