Walking the networks of Denver

Cross-posted at Medium.

Years ago, when I was just moving into the world of urban technology, I stumbled upon the urban “walkshop” format developed by Adam Greenfield and Nurri Kim (refined and expanded by Mayo Nissen). These walking tours were collaborative, lightly-structured investigations of surveillance and communications machinery sprinkled throughout various cities. Though these walkshops pre-dated what some now call the Internet of Things, there was plenty to look at, especially as cameras trained on the public way proliferated.

Sometime later I helped curate the City of Big Data exhibit at the Chicago Architecture Foundation. Being primarily a touring organization, CAF staged a few walking explorations of the collection, transport, and effects of data throughout the city. I was not involved in the development of this tour, though the idea of an “architecture” tour that took as its subject the hiding-in-plain sight constellation of objects, poles, wires, sensors, and cameras that shape a city’s daily life was never far from my mind.

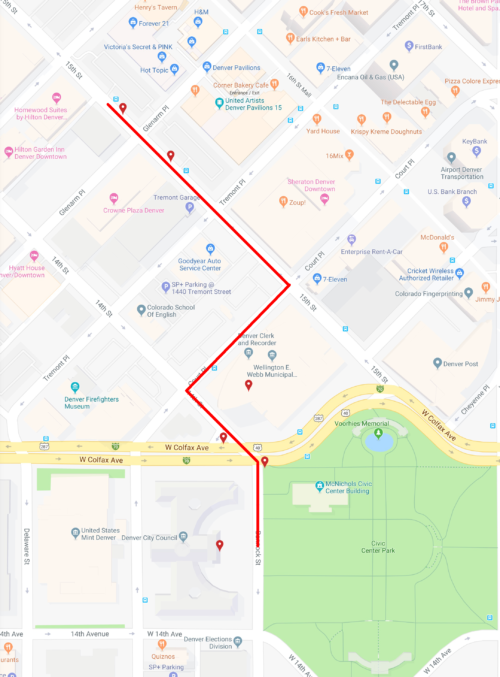

And so it was that yesterday I led a tour of about 20 people during the Denver Architecture Foundation’s Doors Open Denver, our city’s annual two-day invitation to explore architecture and spaces normally off-limits to the general public. Called Networks of Denver: Evolution of a Smart City, the tour was obviously an outgrowth of my work with CityFi. Less obvious – at least to the folks who took the tour, I hope – is that I still feel like a newcomer to Denver; my naïveté about how things work here still feels like license to be aggressively curious. So we set out for 75 minutes to find evidence of digital technology in our physical, urban surroundings.

Why do this? Who cares about unseen boxes and invisible wireless fields? The easy answer to the second question is: a surprising number of folks, with varied backgrounds, most of whom had participated in other, more traditional architecture tours during the weekend. (I suspect we could have filled another tour had I offered it twice.)

Back to the why: my sense is that as more and more urban technology crowds onto our streets it has become increasingly difficult to miss. A few years ago you might never have noticed distributed cellular antennas festooning decaying rooftop water tanks, but today the streetscape is cluttered with many more devices much closer to the sidewalk and roadway. Add to that an increasing awareness amongst the general public that technology is changing the way we use cities: red light cameras flash in our faces leaving us to wonder if we’re driving the car it caught; dockless scooters zip us around then lay in ugly piles on curbs; pay-by-cell options mean never having to run out to feed the meter.

This networked machinery shapes our urban lives. Like brick-and-mortar architecture, the shaping is subtle, often unrealized consciously. Maybe we were given more time to transit the crosswalk because an elderly man was slowly crossing opposite us and a pedestrian video analytics system gave him more time to make it. Maybe you don’t want to picnic in the park because you know the LTE connection there is spotty. Maybe an environmental sensor whose video array is pointed straight up at the sky has informed your hyperlocal weather app which advises you to jump on the bus rather than walk because it knows your few blocks are about to get a sunshower.

With the able assistance of Emily Silverman and Mike Finochio from the City and County of Denver, we were able to look at some things truly inaccessible to the public, including the inside of a traffic signal control cabinet and the city’s traffic management command center. The latter was especially interesting since it is the main terminus of the information being generated from many of the technologies we saw in the field. These included, but were not limited to:

- traffic signal phase and timing controllers

- signal malfunction monitoring units

- two different models of vehicle-to-infrastructure radios (DSRC)

- pan-tilt-zoom traffic cameras

- parking analytics cameras

- pedestrian video analytics cameras

- video and bluetooth-based queue sensors

- emergency vehicle pre-emption radios

- crosswalk analytics sensors

- LTE-enabled parking meters

- WiFi mesh public safety surveillance cameras (“HALO”)

- pavement boxes (electric + fiber)

- distributed antenna systems for cellular (LTE)

- ambient light sensors on street lights

- public electric, dockless scooters

- public docked and dockless bikes

- surveillance cameras on private property

Our discussion of the potential ways that augmented reality could affect the urban realm, for good and for ill, was greatly aided by a five-year-old art/information installation along 14th Street, one of the main corridors we explored. Called the 14th Street Overlay this project has installed antique-looking optical instruments and QR code-enabled placards along the street that attempt to superimpose historical images in situ. How will we behave on sidewalks when we can call up these images on our own devices registered and overlain seemlessly on the physical world? How will that change our sense of place?

We ended our tour looking at two newer and larger installations: a Verizon 5G pole and an information (er, “transit amenity”) kiosk. The thick, towering 5G pole and the number of them required by Verizon and their competitors to blanket the city have lately been a source of some public concern. There was much discussion about the city’s role in making sure such infrastructure blends in to the built environment, either by combining their radios into existing street furniture or requiring that multiple carriers share a common host.

The kiosk was a bit of a disappointment as it is clearly a giant piece of outdoor advertising first, “amenity” second. The public transit information offered is static (i.e., a schedule rather than real-time tracking) and non-interactive. And yet the unit takes up an enormous amount of space on the sidewalk. Apparently most of the inside of the monolith is empty. Most agreed this was a wasted opportunity to do something truly useful in our public way.

I consider the day a success, as I do the version of the tour I gave to my CU grad student class the evening before. Many of the topics that our exploration prompted were about issues of public versus private control and data (observability versus surveillance), how such instrumented intersections could lead to a real-time urban design, ethical concerns about what happens during the transition phase from unconnected to connected vehicles (“is it wrong to provide information to a subset of motorists?”), and how far the city should go to help the private sector test their wares.

This was only the beginning of the conversation. It’s difficult to unsee all this machinery once you know where it is and what it does. I encourage you to go exploring in your city.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into the world of rarely-noticed technologies that shape our cities, I recommend exploring the work of

Ingrid Burrington, Dan Hill, and, Shannon Mattern (including of course Greenfield and Nissen, linked above).

Our state-spanning urban skyline is not made of steel and glass

Cross-posted at Medium.

CityFi partners John Tolva and Story Bellows frequently find themselves on the frontier of urban change. Their facilitation of major projects often convenes public-private stakeholders, utilizes new models of technology and innovation, and drives policy development, all with the goal of making our cities more livable, vibrant and economically competitive. Currently, this mission extends itself to the western frontier of Colorado. These days, the booming Denver-metropolitan region has largely kicked its historical image as that of a dusty cow town; in fact, two of CityFi’s major Colorado-based projects illustrate the innovative, multi-sector and often regional collaborative momentum this state has built toward creating sustainable, positive change for its diverse communities.

The history of CityFi coincides with the beginning of its relationship with the Denver South Economic Development Partnership (Denver South EDP); it was the project to develop a blueprint for turning the Denver South region — a conglomeration of several small cities driven by its economic hub in the Denver Technological Center — into a 21st Century Innovation District, which was the firm’s first. The Blueprint is a critical component to retrofitting this region — a major economic driver for the state, contributing nearly 20 percent of the state’s economic output — so as to keep pace with the urban changes that Denver is undergoing. Denver South is primarily centered around the major artery of Interstate 25, which runs north-south into the heart of downtown Denver. A new study recently projected that in the next ten years, 70,000 additional people would be coming to the region each day to work, highlighting the critical nature and urgency of determining how infrastructure, local culture and the built environment could be transformed to meet these needs in coming years.

As a result, “the blueprint reinvents the approach to making an effective and attractive suburban landscape by providing a guide for city officials and developers as to how to integrate new technology solutions, approaches to policy and governance, improved land use and cultural change,” Bellows said.

For Denver South EDP, this shift is important to maintaining business vitality in the area, as without addressing these barriers, the region risks losing business to other parts of the city, or even other states. The blueprint also leverages one of the most significant investments made in Denver South in recent decades, that of RTD’s transit infrastructure, including a light rail system, which stretches as far southeast as the City of Lone Tree. CityFi wants to better integrate this asset into the built environment to improve Denver South as a place that can accommodate increased people and their desire to live, work and play within proximity.

CityFi sees the challenge of Denver South as also its greatest opportunity. While Denver South may not have the caché or national intrigue of Denver’s downtown core, CityFi recognizes its fundamental importance as part of Denver’s economic engine, and believes formulating its successful future can inform the efforts of other cities also recognizing the benefit of retrofitting aspects of suburbia to accommodate population growth, mobility patterns and new models of the workplace. In short, CityFi sees opportunity to improve development, asset use, business decision-making and policy in Denver South to not only make the region sustainable, but also to improve the quality of life for those that live and/or work in the area. “Citizens everywhere — not just those in the densest, most active parts of a city — deserve the chance to feel truly invested in and love where they live,” Tolva said.

One of Colorado’s particular strengths, including within the Denver South region, is its propensity toward multi-sector and multi-jurisdictional collaboration. This unique asset is significant when considering the scope of retrofitting suburban regions for the future. Rather than decisions made in siloed vacuums, urban change leaders — from city officials and developers, to business leaders and citizens — can collectively work to shape the development of our cities. “Not only does this approach build capacity, it allows problems to be comprehensively addressed so that the resiliency to weather change is strengthened,” Bellows said. This collaborative approach will help to overcome Denver South’s challenges, including defying the misperception that growth and density leads to a lower quality of life for its citizens. Rather, CityFi seeks to reframe this by educating on how population growth and changes to the built environment will actually provide, not take away from, increased choice and connectivity. CityFi and Denver South EDP believe this will become evident as the blueprint is incorporated into future planning practices, and holds the potential to become a national model for how to approach suburban retrofit that accommodate the needs of both old and new residents and workforce.

CityFi’s other major project with Denver South EDP is the ongoing creation of the Colorado Smart Cities Alliance, which capitalizes on CityFi principles of using innovation and technology to solve the complex urban challenges our cities face. The Alliance — while still nimble and in its early stages — serves as an incubator for Smart City pilot projects, living civic labs, resource and best-practice sharing, and multi-sector and jurisdiction engagement around city challenges that cannot necessarily be addressed through traditional government or private sector avenues.

What is most unique about the Alliance, and what is also evident in the Denver South Blueprint, is the additional leverage that regional collaboration and problem-solving bring to the table. While the Alliance originally began under the auspice of Denver South EDP and the cities it represents, it was quickly realized that this effort would increase in value and return on investment for Colorado citizens if it became a statewide project in which all major cities were engaged. While Colorado cities vary greatly — from small mountain towns, to the Western Slope, to the major cities of the I-25 corridor along the Front Range — what is evident is that each of these cities are facing challenges while adapting to rapidly-changing environments, whether urban, rural or suburban.

As the Alliance unfolds, it will have two main roles: first, to solve city problems where solutions do not currently exist through traditional procurement channels; in essence, as Tolva says, “to loosen the innovation throttle inside of cities, and reduce the risk associated with implementing innovation in government structures.” The other main objective will be for cities to be able to capitalize on the economic development opportunities that arise from the resulting multi-city, cross-sector collaboration. As the Alliance incorporates private sector partners, there is a reciprocal return on investment in being able to test new technologies across a variety of city landscapes to understand the true costs and benefits of their application. CityFi’s role is critical in managing the balance between these public and private participants, while recognizing that both parties are necessary to shape the direction of Smart City solutions and provide a pathway for two-way learning.

As is core to its mission, CityFi advises widening the proverbial doors of the Alliance to involve these cities’ citizens in the process. “Too often in Smart City conversations, there are no citizens present. It’s on us to frame the discovery of city challenges in terms of those they affect — business owners, citizens and workforce. That is ultimately the defining philosophy of CityFi,” Tolva said. “Skepticism about Smart City initiatives arises because they are not centered around the citizen experience.”

CityFi’s excitement around its work with the Alliance is palatable; Bellows and Tolva both acknowledge that while many cities have attempted to pull off a similar structure alone, the Alliance is a national trailblazer in terms of conducting these efforts on a regional or state level. In that spirit, Tolva said, “we are less interested in the jurisdictional boundaries than we are in the experience of these places.”

CityFi’s presence in Colorado continues to grow, and is currently working with Denver Mobility Choice, the City of Aspen, and Panasonic on new urban change projects. The Colorado-based CityFi team has also doubled in the past month with the hiring of a new associate. Look for more updates about CityFi’s Colorado projects in upcoming months.

CityFi

Much as I have enjoyed being a gentleman-of-leisure pack mule, fourth-rate interior decorator, and horrible default parent during the move to Denver, it is time to let you know what I’m up to.

I’ve co-founded a company with some of my favorite former colleagues. It’s called CityFi. If you’ve followed me here over the years you won’t be surprised to learn that we’re in the business of helping towns, cities, and metro regions become better places to live and work — whether that’s working for municipalities, urban design firms, architects, real estate developers, or the myriad of companies today whose products or services stand to improve urban life.

Full post over at Medium, but here’s the announcement part:

The CityFi team is a network of professionals who have implemented policies and projects at senior levels in government, foundations, and the private sector. Our team members have proven records of success delivering sustainable, significant change in the way cities work and the way people experience and participate in their communities.

We foster true partnerships that create value for people, for the environment, and for the economy.

We work with innovative global and local companies to deliver top-flight services that enhance the civic experience without imperiling the public good.

At its core, CityFi believes that great cities come not from monolithic projects but rather emerge from carefully-designed underlying conditions — street grids, equitable housing policies, business-friendly regulation — so that beneficial complexity can grow. This is how our most resilient, productive cities have grown for a very long time. We’d like to keep that growth going.

For more information on CityFi and what we do, visit our website and our Twitter feed.

This is an exciting time to be working at the intersection of technology, policy, and urban design. We’re (thankfully) past the techno-utopianist hype of the first wave of “smart cities”. Turns out the world hasn’t stopped urbanizing since then. Lots to do and couldn’t be more ready to get to doing it.

Shaping the tools

Pretty honored to be recognized by Newcity as one of Chicago’s “Design 50”. It’s quite a list to be on.

Photo by Joe Mazza

Here’s the accompanying write-up:

Some designers on this list design furniture, some the buildings the furniture goes inside of, and still others the blocks and developments we put those buildings in. John Tolva goes one better with his latest endeavor, designing the algorithms and systems behind the tools of urban planning. The one-time “data czar” for the City of Chicago has moved on to the private sector where he has been applying his data wizardry and impressive computer science chops in the development of urban planning and visualization technology. As Marshall McLuhan said, “We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.” John Tolva is the man shaping the tools.

Here’s the full list.

I made the list in 2014 too and it contained one of the most unintentionally doleful photos I think anyone has ever taken of me. Glad the photo from this year (above) is the other end of the emotional spectrum.

Thanks, Newcity!

What we talk about when we talk about smart cities

About a century separates the two Scientific American covers above. We’ve been talking about “smart” cities for a long time.

Maybe not in so many words, but the idea of designing a city to optimize it, to make it more efficient, to make its uses more intelligent far pre-dates digital technology. Sometimes the term is at the forefront of urban rhetoric and marketing — during election cycles or after natural disasters, for instance, or when new industry entrants smell a market opportunity.

And sometimes the idea recedes a bit. Recently we’ve seen outright hostility to “smart cities”.

But no matter when we’re talking about smart cities we often do so in terms of particular systems or projects. This city is smart because of its low-carbon transit network. This city is smart because of its waste-to-energy plant. This city is smart because of its predictive policing. And on and on. Or, as above, we can put together top ten lists of projects that will make your city smart. Projects that are so tied to specific new technologies they will either fail or be obsolesced by the volatility of technological change.

A more useful way to talk about smart cities might be to ask questions of a different type. What approach do they take? What is their philosophy of smartness? Who does it benefit in the long run? Below I describe some of these philosophies with design case studies. Though many of these examples are rooted historically, they are not necessarily linear in time — they overlap, circle back, and pop up dressed differently.

The clockwork city is the conception of metropolitan operations most familiar to people. It is an Enlightenment view of the city as a literal machine. One that can be measured, whose gears can be oiled, whose job it is to produce efficiency. It is an engineer’s view of what makes a city work. The city as sum of its infrastructure and services.

One way to understand the clockwork way of thinking is to use the example of public buses. A clockwork view poses the matter of buses as an exercise in operational performance: How can we manage our buses more efficiently? This of course has led to innovations such as timetables. It is an infrastructure-focused view that prioritizes the operator’s needs — essentially asking, in this example, how can we know when buses are supposed to be at a given stop?

There’s nothing wrong with this operational approach, of course, and indeed it has dominated city management for a very long time. What’s useful is to note how this view is the singular focus of most modern “smart city” campaigns, especially with regards to how enterprise technology firms view the challenges in front of a city. Wanting to know where your buses should be is the seed that grows into citywide command centers powered by top-down, command-and-control technologies (such as the one pictured above in Rio). It has been called Dashboard Governance.

There have been many attempts at this kind of smart city. Most are developments from scratch or adjacent districts of established towns. Because ecological sustainability is in theory a more easily quantifiable axis of a city than, say, homelessness or income equality, energy is usually the centerpiece of these types of smart cities. Most have not lived up to their marketing.

There’s a different philosophy of the smart city and it has been driven by the move in recent years to open up city data to the public. Initially undertaken as a political corrective to decades of opaque systems and hard-to-FOIA documents, the open data movement in cities has grown beyond transparency to cities that use it to enforce accountability in its workforce, to analyze patterns and trends for policy interventions, and even as a starting point for companies to add valuable services upon. Open data as economic development.

Using the bus analogy again, instead of the city telling commuters when a bus should be where, an open city approach to design let’s people ask: How can I know where and when a bus will be available? It may seem a subtle distinction, but the difference is enormous. The open city puts the user of the system — in this case the city-dweller — at the center. Decision-making control, if not operational control, of the system moves from inside government to outside.

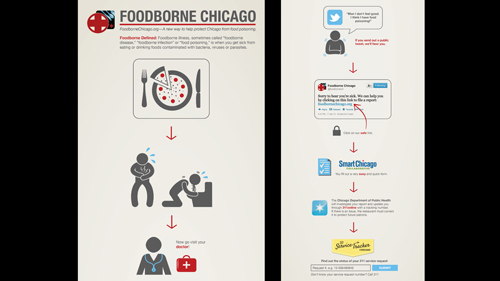

Examples of open city design from the civic tech movement are plentiful. Above, Foodborne Chicago uses public tweets (generated by people totally unconnected to the public health department) to determine whether an instance of food poisoning has occurred.

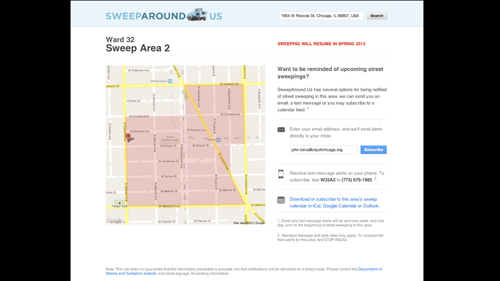

SweepAround.us takes somewhat inscrutable public data about when ticketing will be enforced for street cleaning and proactively alerts residents when they need to move their vehicles.

The open philosophy of the smart city above all focuses on making the city more legible; it isn’t necessarily about citizen-government interaction but about allowing those who live in cities to situate themselves at the center of systems — making sense from the vantage of their personal needs and uses.

The newest perspective is what might be called the emergent city. In this framework initiatives are aimed at changing the underlying conditions that lead to a system’s functions, rather than the system itself. It takes the constituent pieces of the urban experience (whether run by the municipality or not) and joins them loosely through technology to generate different outcomes.

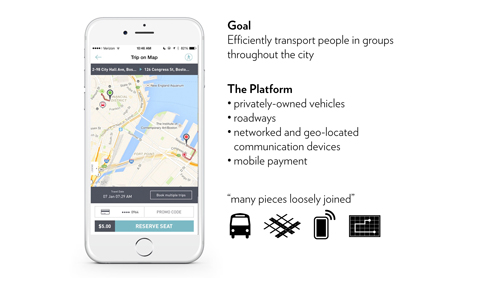

The bus example is again useful. An emergent approach, one that we might also call city-as-platform, asks not when or where a bus is, but rather “What if any vehicle could be a bus?” Typically cities address outcomes, in this case moving people around, but emergent city design seeks to change the initial parameters of a system and let complexity grow from that.

If the goal is to efficiently transport people in groups throughout the city, a centralized bus service is one way to do it. But thinking of mobility as a platform, we can also tally the constituent parts — here, privately-owned vehicles, roadways, networked personal devices, and mobile payment — and ask how they might be made to generate the same outcome as public buses. The example of the Boston company Bridj above is one effort at accomplishing this.

This isn’t about privatizing services so much as it is rethinking a city’s assets — public and private — when overlaid with network technologies. It’s the “sharing economy” with a civic bent: what happens when urbanism focuses on recombinant uses of space and infrastructure. A technologist might call it experimentation-as-a-service.

Projects such as Hello Lamp Post out of Bristol, England have this philosophy in mind as it uses street furniture to prompt local, place-based storytelling. The addition of network technologies to traditional aspects of the cityscape is what allows for the emergence of new uses of the city, new behaviors for its dwellers.

While IT companies push for Internet-aware devices (the “Internet of Things”) largely in the pursuit of operational (clockwork) efficiency, the networked city also offers the possibility of new bottom-up solutions. The Array of Things is a non-governmental project aimed at providing hyperlocal environmental data to whomever wants to use it. (One envisioned use case is to provide information about ice patches that have formed on sidewalks block-by-block.) In both examples, what’s different is that traditionally monolithic infrastructure is atomized and offered up for reuse. Hello Lamp Post and the Array of Things are not solutions to city challenges per se. They change the initial conditions of a system, allowing complexity and the creativity of the urban populace to make something from them.

It’s tempting to think of these three frameworks as evolutionary, one building upon the other. But they are not. There are aspects of all three consistently rubbing up against one another in most cities today. And it is difficult to categorically say that one view is better than another, for that distinction requires acknowledging who the approach benefits. Being smart about smart cities requires asking ourselves who is defining what smart is and who might be sidelined by that definition.

The natural proprietors of the street

A while back Iker Gil of Mas Context asked to interview me for an issue of his magazine focused on the topic of surveillance. The angle was to present data, especially urban data, through the lens of “tracing, archiving, control, camouflage, deletion and monitoring”. The topic was very relevant, given what we know about the NSA and PRISM, but something about the issue’s sole focus on deliberate subterfuge and power imbalance rubbed me the wrong way. I noted to Iker:

“[S]urveillance” is a word fraught with bias towards the act of looking, covertly. What’s going on is much more than that: sensing of all the vital signs of the environment, not just looking at people or their data. That may be what you intend, but it is a partial and distorted picture of the value of instrumented cities. It does not imply any of the benefits of bus trackers, or dynamic tolling, or bridge traction coefficients for warming or any of the other myriad ways the Internet of Things makes our lives better.

Iker was interested in speaking with me based on my advocacy of — and work towards — platforms of public data collection and sharing. I agreed to be part of the issue mostly because I wanted to make the case that there’s nothing inherently nefarious about city data. There’s a line between observation and surveillance — and it needs to be well-limned. Sensible, adaptable urbanism is based on thoughtful observation. Mas Context chose to go with surveillance, which is useful: knowing what’s on the other side of the line is important in being able to draw it accurately.

The full piece is available here.

Cities teem with data because they teem with people using the city. Records of its use — from historical real estate deeds to real-time pedestrian-counting — is data collection. Naturally, news organizations, community groups, activists, and municipal governments have been collecting it for a very long time.

But that’s not the important point. What matters is how it is collected and shared. Collective observation is achieved — and surveillance defused — when the following goals are achieved:

- individual privacy is protected

- the act of data collection is fully transparent

- all collected data is made available openly, free of charge, and in formats that are useful

Drop the ball on any one of these and you have what can rightly be called surveillance. Nail all three and you get what Jane Jacobs called “eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street.”

It’s that second clause — who the eyes belong to — that’s the critical difference. Being looked at (and perhaps not even knowing it) versus doing the looking yourself.

Healthy neighborhoods are those that feel observed (and hence engaged) by its residents. Safe roads are those where everyone — motorists, cyclists, and pedestrians — is equally vigilant. Smart cities are those where people are in the know, period. This can come from a mix of their own observation, a diligent local press (and blogging) corps, and, yes, data that is published about their world collected with notification, openly, and with utmost respect for privacy.

Healthy urban experience depends on eyes upon the street. Let’s make sure those eyes are ours.

“Your moon is on fire”: design and city-making in Helsinki

A few weeks ago I had the pleasure of visiting Helsinki, Finland as a guest of Pluto Finland and Forum Virium. It was a trip long in the making, as I had been extended an invitation by the mayor of Helsinki, Jussi Pajunen, almost two years previously in my role at the City of Chicago. I knew something good was afoot there, so it was time to figure out just what exactly.

Purely by coincidence I was in DC the days before departure and received a tour of Finland’s incredible embassy there. This is not your normal Embassy Row structure. Cantilevered over Rock Creek Park, the building is airy and expansive, feeling almost as much a part of the forest it backs up to as a portal to it. In fact, the grid of the floor plate is “extended” into the trees by way of light-topped poles that repeat the spatial divisions of the interior. It’s a natural-architectural harmony that, one would guess, also underpins the Finnish government’s successful attempt to build the first LEED-certified embassy in the US. Nature as design inspiration and constraint — a theme I’d see repeated many times over the next week.

My exact point of departure was Dulles Airport, the masterful sloping tug-o-war-of-a-building designed by Finnish architect-hero Eero Saarinen. It’s gorgeous and evocative of flight — or at least ascent. Like his arch in St. Louis, which I frequented during my time in graduate school there, the design is a simple curve set against the sky. At Dulles the slope takes humans from ground to the clouds; in St. Louis the Gateway Arch plants the dreams of westward expansion back on earth.

(I thought also of a third curve, not sloping up or down but across: the facade of Saarinen’s IBM building in Yorktown Heights, NY, where I spent much of my early career. The Yorktown building’s architectural conceit is not about bringing people to or from the sky but into contact with one another: no office has an exterior window; the only way to get anywhere or any sunlight is to engage with the hallway formed by the long, gently curving facade.)

All of this an unexpected prologue to the trip. Finnish design escorting me out the door.

Helsinki was named the World Design Capital in 2012. There are many reasons for this honor that have nothing to do with the built environment, but the city itself feels well-crafted, smoothed-out, intentional. New on the scene as a European capital, relatively speaking, Helsinki is a modern city that bears the imprint of what we’d only later call urban planning. That there are very few iconic elements in its cityscape — an Eiffel Tower, a Ponte Vecchio, a Big Ben — focuses attention on the entirety of the place as a designed object.

But there’s also an urgent pragmatism at work. Dan Hill, in his fantastic essay “Designing Finnishness“, describes it as such:

Necessity does not breed frippery, skittishness or carelessness. It breeds purpose, momentum, independence and a belief in technical strength—the art of know-how, nous, savoir-faire.

Necessity, this particular mother of invention, is the challenge of living in such a harsh winter climate, with a gargantuan landmass, minuscule population, and traditionally bellicose neighbors. To survive any of these means being smart and deliberate about how things work. At the urban scale this is about the beauty of efficiency.

Helsinki panorama from Hotel Torni (by Tor Lillqvist)

Helsinki was recently recognized as one of six exemplar “smart cities” in an EU Europe 2020 report which defines a smart city as “a city seeking to address public issues via ICT-based solutions on the basis of a multi-stakeholder, municipally based partnership.” If this is the litmus test for smart by European standards I saw plenty of examples of why Helsinki qualifies.

The municipal government — which provides nearly all public services short of police and military — has moved far beyond the policies and portals of open data of its Western European counterparts. Nearly everyone I talked to, including deputy mayors Hannu Penttilä and Pekka Sauri and the mayor himself, was keen to show me the applications that have been built upon the Open Ahjo API for accessing materials related to the deliberation of procedures and laws. Put another way, Helsinki has an open API for the process of democracy rather than simply a portal for the results of it. This is a huge deal: debate transcripts, legislative emendations, recorded minutes — all synchronized and designed for ease-of-access and cross-reference. It’s a real-time wiki for how city government is making decisions. This is what open data in the US needs to aspire to.

How’d they get to this point of extreme transparency? I have no definitive answer, but it doesn’t hurt that Estonia and its capital Tallinn right across the Gulf of Finland is a champion of digital government. While there’s a history of affinity and commerce between these two cities, you get a whiff of competitiveness when Finns note that for Estonia, who long suffered the very opposite of open government under Soviet occupation, “it is easy when you start from nothing”.

Data, not just transcribed conversation, is the bedrock of a city that seeks to be a platform for innovation outside of government. And Helsinki leads in that arena as well. They actually have a department called Urban Facts, which would be funny if it weren’t so good at what it does. More important — certainly more worthy of emulation — is the Helsinki Region Infoshare portal. All cities exist as part of metropolitan regions; data does not stop at jurisdictional borders. While the Infoshare does not normalize data across cities, it does make it easily accessible — a first step to the real win of data standards between cities.

The key in the EU definition of smart city, above, is “multi-stakeholder”. The first wave of smart city rhetoric focused on government and infrastructure, almost as closed systems, enterprise and top-down. But what’s clear to nearly everyone actually involved in technology for cities is that it’s actually innovation outside (sometimes just on the periphery) of government that effects the real change. But that swirling mass of talent and activism outside government often needs a center of gravity. In Chicago that’s the Smart Chicago Collaborative; in Helsinki it is Forum Virium, specifically their Smart City project area.

Forum Virium serves an important role of organizing the various communities involved in digital city-making. Led by the polymath dynamo Jarmo Eskelinen, Forum Virium is part matchmaker, part grant-seeker, part center of knowledge for all things smart city.

One project of real note under Forum Virium’s purview is the Kalasatama smart district project. One of several brownfield waterfront in-fill projects in Helsinki (heavy shipping has mostly moved to other areas in the region), Kalasatama is the testing ground for new technologies in the urban fabric. Unlike first wave smart cities like Masdar and Songdo, however, this district is right in the middle of Helsinki. The project, called Fiksu Kalasatama, aims to improve energy consumption, transportation and social services through integrated systems and ease-of-access and, while, it is early in the planning phase, it is clear that the goal is to serve as a pilot for scaling into Helsinki proper.

Creative Finnish city-making sometimes has no digital component at all. Would you believe Helsinki is the epicenter of wooden skyscraper design? That’s right, wooden. And tall. The huge swath of forests north of Helsinki created a world-leading paper and pulp industry for decades in Finland, but the rise of online communication is forcing major timber companies to rethink the end-uses of their product. The paper company Stora Enso is currently developing Wood City, an entire district in the city built of timber.

Chicago, you may know, has something of a history with crappy, flammable wooden structures — so the idea of Wood City at first gave me pause. But I was impressed by the engineering and science behind the plans for construction. Wood of course burns, but, as was demonstrated, when subjected to flame cross-laminated timber essentially chars a protective cocoon around the structure-bearing beam at the core.

There are many appealing architectural and sensory (olfactory!) implications of very large wooden structures, but perhaps the most important is that wooden structures are far more malleable over time than steel and brick. Stewart Brand’s notion of a building’s “shearing layers” — its site, structure, skin, and services — that all evolve at different rates has long been fundamental to smartly-designed buildings. There’s something very code-like and mutable about a building as open to modification as those Stora Enso is constructing. (It’s no wonder shearing layers has been adopted as a concept in software too.) Nature here not so much as design constraint as advantage.

In Espoo, a large suburb of Helsinki best known as the home of Nokia, I had a chance to visit the UrbanMill (speaking of shearing and timber, ahem). UrbanMill is an incubator for startups focusing on civic innovation. It’s a sign of some maturity in the Finnish startup ecosystem that something as specialized as a city-focused startup space even exists. There are very few in the US, but the opportunity space is huge.

What’s exciting about UrbanMill is less its projects, which are excellent, but that the startup energy in Helsinki is off the charts, evident most proximately by its next-door neighbor Startup Sauna. Rovio’s Angry Birds and Supercell’s Clash of Clans are two of the most successful examples, but tech-savvy entrepreneurs are pouring out of Helsinki’s universities and into other application areas as well. If even a fraction of these folks choose to tackle the problems inherent in cities — mobility, social justice, public safety, the list is endless — Helsinki will have a leg up.

The Microsoft acquisition of Nokia was finalized while I was in Helsinki. Time will tell how this merger turns out, but history suggests it won’t be easy for the Nokia brand to thrive under Microsoft’s stewardship. And this, ultimately, is a good thing. The effect of Nokia on Helsinki is tangible — I’ve never, for instance, seen so many people using Windows Phones — but it has also been an enormous magnet for technical talent in the region. That magnetism is weakening which means more opportunities for engineers and computer developers to join smaller firms or start their own. It’s time for new centers of gravity to form in Helsinki’s industrial galaxy. This can only be good.

Helsinki was a lot of fun too. I happened to be there the week of one of Finland’s biggest public holidays. Called Vappu, May Day elsewhere, it corresponds to the graduation of thousands of Finnish high school students. On the eve of Vappu the central plaza of Helsinki fills to capacity to watch the tradition of “crowning” the statue called Havis Amanda with a university cap (looking somewhat like a sailor’s hat). At that point everyone else is obliged to put their university caps on (including people who graduated decades ago) then basically spend the next 36 hours drinking, picnicking and making merry.

I was also honored to be invited to DJ “Chicago Night” at a local bar on Vappu eve eve. Coming the week after Frankie Knuckles died, you can imagine the playlist.

I cannot not comment on the beauty of the Finnish institution of saunas. The basement of the embassy in DC is a vast, gorgeous sauna (the only Finnish word in English parlance), where the ambassador holds official meetings. At the Kotiharjun sauna in Helsinki I had the privilege of meeting with the incredible Open Knowledge Finland group. Casual, public meeting places like this are, alas, on the decline in Finland, primarily because new residential development almost always allows for in-unit or shared-unit saunas. This is a shame as the sauna as a social institution is an incredible social equalizer. Everyone is the same when they are sweating, hardly breathing, and nude. A lesson for city-makers, indeed.

My visit to Finland came a few weeks after a similar trip to Italy. The contrast could not have been more stark. Fiery, mobilized, sometimes angry Italian civic innovators railed against a common cause — usually the government itself. I didn’t see that in Helsinki. Government seems to be running just fine. The leaders get open data and government and seem to fairly finely tuned into the urbanist needs of the city itself. And so I was left wondering: isn’t part of the appeal of a city the resistance in the material, a little bit of grit in the gears? Real creativity is born of friction — psychological, sociological, political. Beyond surviving the climate what is the passion that stirs Finns to design what they do?

I do not have an answer to this. I was there less than a week. But I would love insight. I do know that the primacy of design in urban matters as a counterbalance to tech-heavy “smart city” rhetoric is welcome. We won’t get to truly smart cities with engineering and computer science alone. It takes “the art of know-how, nous, savoir-faire” as Dan Hill put it, something designers excel at. Finland can be the vanguard of the second wave of smart cities.

A note on the title of this post. The week after I was in Helsinki this tweet came through, which pretty aptly summarizes the inscrutability of the Finnish language. I can fake my way through most of the Romance languages. But Finnish, forget it.

Crash course into Finnish language via @Me_Pia1 #Finland #Finnishlanguage #visitfinland pic.twitter.com/BeIoN7oFdB

— Visit Finland (@OurFinland) May 13, 2014

Helsinki’s moon, Nokia, is on fire. But the city’s skill at design, experience in open city government, and activated civic actors outside of city government form a bright sun. One hopes that the almost-perpetual summer sun in Helsinki is a metaphor for things to come.

City of Big Data

Newcity has published an edited transcript of a conversation I had with writer Phil Barash about design, data, and urban systems. It’s a lotta words, but does, in a way, capture more fully my thinking on data-informed urban design than anything that’s previously been published. So I’m glad for that.

Here’s the full piece: Bright Lights, Big Data: How the Hog Butcher became the Data Cruncher.

The story is timed to coincide with the opening of the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s City of Big Data exhibit. If you live in Chicago — or are visiting (the CAF architecture river cruise is the most popular thing to do in the city) — you really should check it out. Answer questions such as: What does information architecture have to do with the built environment? How did the fire of 1871 kick off Chicago’s obsession with urban data? And, just what in the hell does Carl Sandburg have to do with big data?

Bonus: it features a 3D-printed monochrome cityscape used as a “canvas” on which data visualization is projected. Spectacular, immediate, and physical.

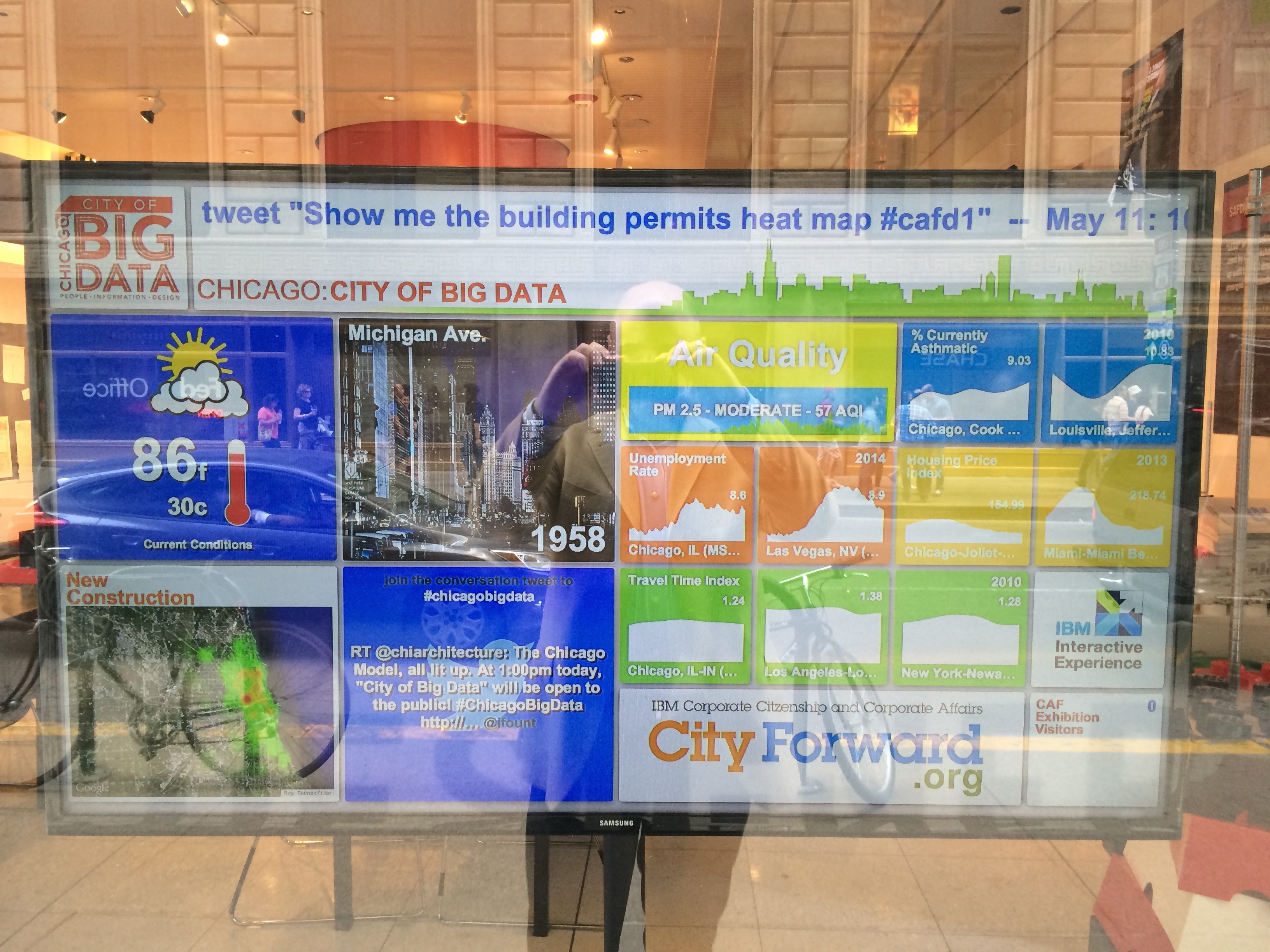

The exhibit also features a custom dashboard of city vital signs, developed by my old IBM City Forward team. Two special panels face Michigan and Jackson for data-flâneurs and other passersby.

Optional caption of above photo: self-portrait with all professional pursuits to date, 2014.

Notes on a “smart” tour of Italy

I’m recently back from a short tour of Italian cities — Milan, Turin, Rome and Florence — where I met with entrepreneurs, company leaders, academics, and government officials on the topic of “smart cities”.

The term “smart city” has received some cogent criticism of late. (See Greenfield and Townsend.) It’s a marketing buzzword that’s become a policymaker catchphrase and, at least in the United States, is met with whatever just precedes skepticism. But elsewhere in the world, the phrase seems earlier in the hype curve. The overwhelming sense I got in Italy is that “smart city” means everything — or possibly nothing — and is code for “what does technology mean for making our cities better?”

The simplest way I heard that question put was by an editor of La Stampa newspaper who noted that when the iPhone came out no one knew what “smartphone” meant. But now, as he said, everyone understands the difference between a feature phone and a smartphone. The implication was: when will we all have a common understanding of the “smart city”? Many city leaders wonder the same thing. I recently had a minister of a country ask me what software needed installing “to get a smart city”. /facepalm

Before attempting an answer at that let’s situate back in Italy. Italian cities are relative latecomers to the the open data/smart city/networked urbanism world. While European cities like Copenhagen, London and Barcelona race ahead it seems that Italian cities are only just embracing the concept. Many reasons were offered to rationalize this while I was there.

The first impediment, an entrenched bureaucracy with zero motivation to change the status quo, was the most common complaint, though I often thought of my own city — and its legacy of machine politics — as one example where the chief executive, in this case our mayor, confronted that bureaucracy head-on and was able to relatively painlessly make open government and nimble IT standard operating procedure within city government.

Leadership, especially at the municipal level where the reality of life is at its most immediate and the buck cannot be passed to a “lower” level of government, is absolutely critical. I saw this in a few cases in Italy. Mayor Piero Fassino of Turin seems to get it. Turin, like Chicago, was a town made prosperous through much of the 20th century by manufacturing. With its reliance on the automotive industry and the pressures of globalization Turin struggles, like Detroit, with market diversification and the cultural warping brought about by the primacy of the automobile.

But Turin seems to have turned it around. Downtown is as lovely as the pedestrian-friendly city centers of other Italian cities, finally, and their industrial base has turned their manufacturing excellence into an asset for branching into other fields beyond automotive. (In fact, the governor of Michigan was in Turin when I was there to figure out just how they’ve pulled it off.) Like Mayor Emanuel in Chicago, Mayor Fassino is a strong, nationally-known political leader who served in the central government for many years. His ties to the Italian parliament but singular focus on Turin has given rise to the most comprehensive smart city plan in Italy.

So, yes, leadership is key. But this is not a particularly useful insight. The question is: why are Italian leaders averse to embracing technology in the way that their other European peers do? What I heard, obliquely, is that the system is set up such that leaders endeavor to please their party rather than the civic populace. But how does this not characterize most political systems, the US very much not excepted?

The difference, I think, is a lack of critical pressure from outside of government. While I met with many civic innovators, activists and hackers, the groups seemed fragmentary — or, rather, without a real center of gravity. That center elsewhere in the West is almost always a fecund resource for building things, a ready supply of raw material — and it is almost always open, machine-readable, frequently-updated data about how cities are being used. The open data movement is nascent in Italy and this too is something that can really only be changed through political will and policy change. It’s the catalyst, the platform, for any smart city.

I also got an earful about the twin red herrings of open government: “What about privacy?” and “Won’t giving people data about the city create too much expectation for more?” These are both commonplace reactions and litmus tests for the fear attendant in political cultures who believe that information is the government’s to control, rather than the people’s to own. It is, after all, city-dwellers using the city that generates — and pays for — the data.

Privacy, obviously, is paramount — moreso in a world after Edward Snowden and revelations about the NSA. But Italy seems to have a handle on this, at least legislatively. One example: It’s been a few years since I was last in the country and I was struck by the amount of signage very forthrightly delineating areas of video surveillance. It’s actually somewhat gaudy, but all the signage suggests a culture at least activated about the implication of technology on privacy. If government can be proactive about alerting people to surveillance surely they can be thorough about protecting privacy in open data releases, the vast majority of which contains no personally identifying information whatsoever.

Challenges aside, Italy actually has much going for it. Culturally there’s a strong foundation for smart urbanism.

Italy basically invented urban planning, the architecture-like approach to city-scale layout that is at least nominally at the heart of urban planning today. Pienza, perched hill-top in Tuscany, is credited as the birthplace of Renaissance Urbanism and even today evokes a kind of civic intelligence that should be instructive as we move into overlaying networks on public space. There’s no reason Italy shouldn’t feel more than normally motivated to claim first place in smart urban design through technology.

Even when not centrally planned, the very age and unplannedness of Italy’s city centers lays out a path for smart urbanism. Narrow, labyrinthine streets may confound mapmakers, but they are the very essence of complete streets — a concept Italy has embraced since before it was a transportation engineer’s meme. Cities in Italian cores are open in a way that the “smart city” idea of openness ought to emulate. Americans may hate them, but the ZTL (Zona a Traffico Limitato) is a model for how municipal governments should treat the entire public way: access for everyone, including its non-physical vital signs like data.

Italy understands the power of design, period. And has built a global brand on it. Fashion is what’s most known, but let’s not forget the Renaissance and automobiles and the overall savoir faire of Italians in general. There’s no more ripe space to apply this distinct global advantage than in the service of Italian cities.

Italians love mobility. They may not have been the first in Europe with high-speed rail (though the Frecciarossa is pretty great), but who can deny that the culture of scooters and mobile phones — the latter of which was far more ubiquitous far earlier than any country I’ve ever known — doesn’t point to a citizenry ready for decentralized, data-informed urban life?

Italy perfected the city-state after Greek models and, as of the first of this year, the country is moving towards governance models that recognize the power of metropolitan regions at scale. The Città metropolitana changes to the Italian constitution amalgamate regional governance into 10 (possibly 14) conurbations. This bodes well for smart cities, since such are built on standards and interoperability between all players.

Opportunities are plentiful for smart cities specific to Italy:

- Transparency in a political culture tainted by high turnover and data opacity.

- Technology-enabled navigation where streets are a complex warren of restrictions and barely-Euclidean geometry. GPS just doesn’t cut it.

- Italian is one of the less-spoken European languages and yet their economy is fueled by visitors. This is opportunity for technology.

- As with most countries, energy independence has equal geo-politically importance with environmental stewardship. Italy’s historical manufacturing and engineering legacy can be retooled to capitalize on this new reality.

When I worked for the City of Chicago we never used the phrase “smart city”. As an abstract concept, it just wasn’t part of our day-to-day work. For one, cities can do smart things wholly apart from technology. “Open government,” “civic innovation,” even “networked urbanism” were what we called what we did, when we called it anything at all.

I was pressed in Italy to define “smart city” and the answer is that cities have always been smart. They are one of humanity’s greatest inventions. Italy especially has good examples of well-wrought, thoughtful urban experiences.

But the actual term of course has a valence today apart from this. Smart cities build upon the density, diversity, and proximity that characterize all great cities through sophisticated mechanisms of listening to their own vital signs. “Smart” here is self-awareness — whether through advanced, open sensors, policies of open data, or systems for citizen engagement. Feedback loops, abetted by technology, at hyperlocal resolution and close to real-time are the agents of diagnosis and change for the smart city.

Italy can make the leap — and in fact can capitalize on what has made it a center of urban innovation historically: design skill, organic urbanism, hyper-mobililty, and metro regional governance. “Smart” or not, it’s time to upgrade that urban feature phone.

From City work to city work

Pleased to announce that I have recently joined PositivEnergy Practice as its president. PEP, as it is known, is a small engineering firm in Chicago that does big things — as in really tall and very complicated things.

I’m leading a group of talented engineers who design (and re-design) buildings, districts and cities. PEP’s speciality is high-performance, clean tech engineering focused on new structures, retrofits, and urban ecologies of infrastructure. Much of our work is done for — or in partnership with — architecture firms.

Exciting times, these. The tools of data analytics (and the open data itself pouring out of many cities) make this an optimal moment to bring performance simulation to a new level. Likewise, as devices and sensors proliferate throughout our urban areas design and engineering firms — who already understand complex physical systems and the human needs of the spaces they engineer — are well-positioned to potentially remake the notion of “smart” cities and infrastructure.

Crain’s has a short piece on this today as does the PEP website.

Woo!