Hack the planet: Spore and Worldchanging

The two most powerful presentations I saw at South by Southwest concerned vastly different topics — gaming and environmentalism — but their essence was the same. How to engineer a planet?

The first was Will Wright’s mile-a-minute discussion of interactive narrative and demo of the upcoming Spore (update: video) .Then, later that day was Alex Steffen’s captivating Worldchanging exploration of living for a sustainable future (udpate: podcast).

Spore of course is really Wright’s “SimUniverse,” starting you off in the protoplasmic goop as a unicellular creature in search of not dying and concluding, if evolution is kind, with you at the helm of a stable, interstellar civilization. Spore is, in short, a massive modeling tool for the complex systems that make up a world. It looks like a hell of a lot of fun.

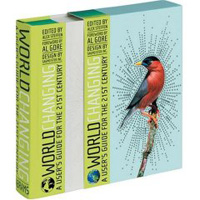

Steffen’s presentation was about modeling a future world too, though in this case it is the one we’re currently living on. Where An Inconvenient Truth highlighted the problem, Steffen’s site, book, and organization work to demonstrate solutions. He is a powerful speaker. The audience was as spellbound as it was during the Spore demo and probably for the same reason: waiting raptly to find out how this particular world was going to turn out.

Both the game and the strategy for a sustainable Earth have to do with little things that have big consequences. In Spore this might be giving your creature asymmetrical appendages, something which may serve you well when foraging in nooks and crannies but which might turn out to be a liability in hand-to-hand combat or when piloting a spaceship. In Worldchanging, it might be car-sharing, for people who share a vehicle tend to be more efficient drivers since they have to plan their excursions. Both talks were essentially about sliding the scale on civilization and seeing what happens, what Steven Johnson calls The Long Zoom. (His recent book, The Ghost Map, focuses on the interplay of scale between the cholera microorganism and the urban patterns of 19th century London.)

Wright calls interactive narrative of this sort “filling in possibility space”. There’s always structure and constraint, but an element of free will allows for gameplay. You might argue the same goes for environmentalism. Natural resources, physics, and the human imagination are our constraints. We must merely fill in the possibility space, change the narrative for a happier ending.

Wright says that “the process of playing the game is the process of making assets for the game.” You could say the same thing about SimCity too, of course, but you could also say that about life. If life is a game — and in non-trivial ways, it is: a set of goal-directed actions to maximize returns — then we’ve got a rather tidy analogy on our hands. You don’t live in a static world; you make the world as you live.

Consider these quotes:

“One must dematerialize the extraneous stuff that gets in the way of the experiences we want.”

“Compact living in well-designed cities dematerializes transportation and infrastructure allowing access by proximity.”

“Many things are only garbage when they are in the wrong place.”

All from Steffen, all about eco-friendly living. But they’re absolutely relevant to Spore. Which isn’t to say that Spore is an in-your-face green manifesto. It isn’t. You might create a perfectly sustainable planet with oceans of methane. But in doing so you’ve foreclosed many possibility spaces suitable to human beings. Fun in a game, not so fun for carbon-based lifeforms.

Some other bits I found interesting in the Worldchanging session:

Car-sharing is an old idea (it just sounds 1970’s) made useful only through recent mapping and GPS technologies. ZipCar and iGo are successful because technology has finally made it easy for people to find a car when they need one.

Steffen asked how many in the audience owned power drills. Most hands went up. (This was a geekfest after all.) He then told us that the average power drill gets used for six to twenty minutes in its entire life — an epitome of unsustainable waste. What we want is the hole not the drill.

Measuring things changes the way you use them. The example he gave came from the UK where a test group had their energy meters moved inside the house. This act by itself reduced power consumption. When you see the meter you think about the meter and when you think about it you turn the lights off.

Why can’t we separate practical objects from objects that mean something to us? Your childhood teddy bear means something to you emotionally, where your washing machine most likely doesn’t. What if most practical objects were leased rather than owned? The effect would be greener production. If a cell phone manufacturer had to take the phone back at the end of its useful life the company would be far more likely to make it easy to recycle. (Steffen called computers — which nearly everyone in the audience had on their lap — an “environmental nightmare” because of their unrecyclability.)

It was interesting to me that some of the technologies found in the third world are the greenest: evaporative refrigeration, fog-catchers, rainwater recyclers, wired infrastructure leapfrogging.

The final bit of advice was to “green your geek.” Don’t stay up at night worrying about paper versus plastic. Rather focus on whatever you are really into (i.e., “your geek”) and try to change just that. Simple, potentially powerful.

In the end these two sessions about Spore and Worldchanging kinda merged in my head. To create a sustainable world you have to imagine what you want, then build it. Spore gives us a simulator; Worldchanging gives us an imperative.

Reminds me of the History Channel City of the Future design challenge. Much more on this soon!

As a sidenote, it’s been remarked that the panel-heavy structure of South by Southwest doesn’t allow for sustained exploration of an idea. I’m still a fan of the conversational tone of the panels, but in looking back on the week that was I admit that the three most powerful sessions I attended had a single speaker.

City of the Future

Urban Labs’ “Growing Water” design for a future Chicago wins The History Channel’s City of the Future design challenge. It is a really smart concept.

Let me summarize:

- Start with the turn-of-last-century “Emerald Necklace” of parks and boulevards meant to create a green orbital around the city. (It sorta works and makes a great bike route.) Use this as a lush anchor for what’s to come.

- Return to a respect for the subcontintental divide that splits water flowing to the Mississippi from water flowing to Lake Michigan (the solution to this Ascent Stage quiz of yore) and the fact that the Chicago River now disregards this natural phenom based on human engineering. (Or does it?)

- Repurpose the current labyrinth of water and sewage tunnels to house the much-desired expansion of the L. (Urban Labs meet Craig Berman, discuss.)

Yes, IBM, was a sponsor of this competition. Alas, I had no part in the judging.

Ore consequences

My parents recently built a second home in Galena, IL. Galena is in the far northwest corner of the state, nestled between Iowa and Wisconsin. It was a major river town in the 19th century, home to Ulysses Grant and a slew of other Union generals. But the river silted up, Chicago grew up, and Galena slumbered away. Now it is basically a quaint time capsule catering to Chicago weekend escapees, the kitschy knick-knack obsessed, and Civil War buffs.

Galena is the word for lead sulfide, veins of which criss-cross the area. As luck would have it, my parents’ land has an abandoned lead mine on it. This isn’t suburbia; the lots have (fantastically) reverted to native Illinois prairie. But it was once farmland and apparently the owners way back found a small lode and went for it. The builders of my parents’ home wanted to fill the mine entrance in with excavated soil and landscape it. My father, to his infinite credit, said screw that I want a lead mine on my property. And this brings us to today when I had to enter and see what there was to see.

I’ll preface this by saying that my adventure was not formally approved by the family. My boys of course were right there with me but mama’s look of disapproval, had it been cast groundward, could have dug its own mine.

I struggle to list a hazard that this mine doesn’t contain so in the interest of having something to blog about I’ll here detail those that it does. The mine is completely structurally unsound, having been abandoned more than a century ago. The whole reason for digging it in the first place is because it contains lead, the very substance that causes parents to obsess about our kids eating paint. It is wildly overgrown and so home to all manner of critters, vermin, and poison flora. There are tons of snakes in these parts and my dad mentioned that he saw something “dog-sized” leaving the shaft yesterday morning. Hmmm, lovely.

So I went in. The kids, standing at the rim of the depression that led to the shaft, were nearly apoplectic with excitement. And while we’re using apoplexy as a metaphor I’ll mention that it also described my wife at this moment, but for very different reasons.

The shaft entrance had long ago been filled in. Metal containers of all varieties, a tire, and barbed wire clogged the hole. I struggled to loose them but the entrance was a garbage pit. Every time I unearthed a rusty shard I expected some venomous slitherer to inform me of its displeasure. A wooden beam — really a crudely shaped log — lay uphill from me in the overgrowth and seemed to mark the entrance to the shaft. My father, lost to me but for yelling, agreed that the best plan was to wait for fall when the foliage died off and then resume digging. Actually he wants to rent a ground radar to see what we’re up against. He thinks he’s identified a second entrance (exit?) nearby.

In the end this is just good fun. How many kids grow up with an abandoned lead mine as a playlot? Too few, I say.