Unfriendly Confines

Prefer to listen to this post?

You’re in a box. It’s dark. There’s only one thing to focus on. You really can’t make noise. Are you in a coffin or are you in a movie theater?

Greetings, travelers! And welcome to the first itinerary where we really don’t go anywhere. Or rather, the places we’ll visit just aren’t very spacious. It’ll be hard to move around much at all, so take a load off and try to relax as we explore a segment called Unfriendly Confines.

The earliest motion pictures were stage plays performed in front of a camera. How could it have been otherwise? The only directors around then were theatrically trained, so cameras were stationary like the fixed vantage of playhouse audiences. Actors were not yet accustomed to the nuance available when you didn’t have to shout your lines for the cheap seats to hear. The visual language of cinema was still in its infancy.

But we lost something once cinema figured out rapid cuts, unique angles, and sprawling panoramas. Single location films or ”bottle episodes” in TV, as they are respectively known, automatically heighten drama — or at least provide an opportunity for heightened drama — given their intimacy. It’s the same way you lean in to someone when you want to tell them something important … or give them a smooch. Tight quarters are always more dramatic, sometimes in a positive way and often in a very negative way. We of course will focus here on the negative. But before we get to that let’s also consider just the plain economics of single location filmmaking. It’s so much cheaper. Of course we love sprawling epics on the big screen, but a modestly successful film shot in one location — minus the expense of multiple sets, equipment transportation, location producers, etc — almost certainly means your film will make a lot of money.

Most single location movies are thrillers or horror. The reason should be obvious. With very little to look at or to propel the story other than the characters themselves the script (and dialogue) will necessarily be a deep dive into psychological states. Put another way, the space of a single location film is interior rather than exterior. And that can be very very scary, when done well. In the realm specifically of horror, single location films often devolves into claustrophobia. The space itself is a sort of character, providing motivation or challenge or frights simply by being so damn cramped.

Searching for historical beginnings in this micro-sub-genre is complicated by the limited spatial scope of all early silent films. Still The Cat and the Canary from 1927 is generally considered a starting point — and not just of tightly-constrained horror but of the entire “old dark house” setting that characterized so many Universal films through the 1950s. This film — originally a stage play, unsurprisingly — pulls a bunch of family members to a decrepit old house for the reading of a will which leaves all of the decedent’s estate to his most distant relative providing she can be proven sane after spending a night in the mansion. If not, there’s a second will to be opened denoting a different heir. Hijinks ensue (this is, in part, a comedy-horror) and an escaped asylum patient called “The Cat” enters the picture. It’s a fun watch, especially to see what later filmmakers built upon when mining for haunted house tropes and motifs. Note especially the hairy, long-nailed hand reaching through the wall at various points. The Cat and the Canary basically started the we’re-all-stuck-in-a-spooky-house-tonight theme and it’s still going. There’s a straight if dotted line from this film to 2019’s Ready or Not, also about a woman who must survive the night with family in a kooky mansion.

So let’s look at some confined space movies, going from roomiest to most cloying, like a slow-moving trash compactor.

Let’s start in a grocery store. And you know, it sure is foggy outside. That’s right, it’s The Mist from 2007, Frank Darabont’s re-telling of the classic Stephen King novella. Obviously a supermarket is not all that constrained as far as spaces go — and it is certainly well-provisioned. But the interplay of personality types surrounded by an unknown danger outside the all-glass facade of the building makes it seem a heck of a lot smaller. Interpersonal disagreements about what to do escalate quickly as evidence of the mortal peril the shoppers are in becomes unavoidable. So here’s my First Axiom of Single Location Horror: conflict shrinks space. No matter how roomy your confines, when things go south the drama ratchets up. Think about the last time you were on a subway, everyone minding their own business, and then someone does something causing upset (yelling, unwanted solicitation, vomit, whatever). Drama up, you shrink into yourself. The walls close in a bit.

We’ve left the grocery store, safely somehow, but we’re headed to our car, alone, in a parking garage. This movie is P2 also from 2007, a tale featuring only two people in the garage on Christmas Eve. Angela, just trying to go home for the holidays, and Thomas a security guard who also turns out to be a molesting, murderous psychopath. Some spaces — no matter how roomy — seem cloying. I’d put parking garages, especially at night, high on this list. They are never lit well enough, smell of gasoline, and there are no right angles along the x axis, which is disconcerting to the human brain. There’s a safe space, your car, but you have to find it and that in itself can be a source of anxiety. What makes this film work is how inhuman the space is. Parking garages are car storage; they are not for people. Just raw concrete and stains. So the Second Axiom of Single Location Horror: constraint isn’t only about square footage; it’s also a function of habitability.

Let’s go vertical a bit with Robert Eggers 2019 The Lighthouse. Like P2 this one features only two actual people. It’s a great example of psychological horror bleeding into mythological horror. Much has been noted about the standout performances of Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson in this tale of isolation and creeping lunacy. It’s a fantastic movie. You should watch it. You’ll get the sense of claustrophobia on this rock immediately. The point I want to make is that the job of a lighthouse is to demarcate space, but in an odd way. The light beacon is both saying “your boat shouldn’t be here or it’ll wreck” and “your boat is on the right path, good job, here’s your waypoint, keep going for safe harbor”. Put another way, it’s saying “get close, but not too close”. Uncomfortable quarters indeed.

Of note, Eggers shot this film in the unusual aspect ratio of 1.19:1, which is almost a square. Known as the Movietone ratio this was used mostly between 1926 and 1932 as silent films were transitioning to talkies. So in addition to reminding cinema nerds of this early phase of stage play films, or reminding today’s congenitally online hordes of Snapchat and Instagram videos, it’s an incredibly crammed visual space to work inside. Not unlike, say, a lighthouse. The film is also shot in black and white. There are nostalgic reasons for this, of course, but technically black and white film reduces the visual clutter, highlighting shape and pattern with the removal of color. It doesn’t make a space smaller, necessarily, but it makes what’s in the frame stand out with more contrast. Negative space is easier to highlight and bright light, overblown like a Fresnel lens swinging around in front of you, immediately consumes the whole space. All of which to deliver the Third Axiom of Single Location Horror: technical creativity in film can be just as useful in creating close quarters as the physical aspects of the set.

Sometimes the confined space is a literal stand-in for us, the viewers, sitting rapt in the theater. All iterations of voyeurism horror owe a debt to the great Rear Window from 1954 by Alfred Hitchcock. Rear Window is emblematic of and a possible decoder for Hitchcock’s obsession with single location (even single take) filmmaking — see Lifeboat, Rope, Dial M for Murder, and of course the shower scene from Psycho. More than anything Hitchcock here seemed interested in using confinement (literal in this case as James Stewart’s character is wheelchair-bound in his apartment for almost the entirety) to make a comment on the act of viewing and our desires as viewers. Those desires include morbid curiosity and male sexual fantasy. And that right there is a good description of the popularity of at least some genres of horror, like 80s slashers. It also is useful biographically when considering Hitchcock’s rampant misogyny. I love this movie for many reasons, but lately it seems even more relevant as hordes of would-be sleuths sit entranced by their computer or phone screens, Rear Window-like, attempting to solve mysteries of what they think is happening in the outside world. Looking at you, conspiracy theorists. But let’s return. The Fourth Axiom of Single Location Horror: often the constraint imposed by the space permits an extended view outward, revealing frights that would otherwise go unnoticed. Peeping Tom, One Hour Photo, and the somewhat recent The Voyeurs are good examples — though there are dozens of others.

Getting cabin fever yet? Climbing the walls? Maybe just seasonal affective disorder? Let’s quickly run through three very different films all of which showcase the diversity of confined spaces. Say what you will about M. Night Shyamalan, but his story for 2010’s Devil is 80 minutes of tight frights. Devil takes place almost entirely in a stuck elevator with five occupants aboard. One of them, it turns out, is Satan himself. Or herself. The lights continually flicker and usually there’s some new mayhem to deal with when the lights return. The five naturally start accusing one another. As ever with M. Night there’s a twist or at least an unforeseen reveal at the end. It certainly got me.

Then there’s Open Water from 2004 about two scuba divers in the tropics who surface to learn that their dive boat has left without them. That’s pretty much the movie: pure survival horror. The irony here is that the open sea could not be a less constrained space. You can go for miles in any direction (including down). Except of course you can’t because you have to eat, you’ll get cold, and you’ll eventually run out of energy. And oh and let’s not forget stinging jellyfish and hungry sharks. So you’re stranded by biological need rather than anything else. In some ways it’s worse than a broken elevator.

Changing climates we arrive at Frozen — no not that one — the one from 2010 that follows three snowboarding buddies who are stranded on a chairlift when the ski hill operators forget they’re there and shuts down for the weekend. This is also survival horror of course — where the threat is dehydration and freezing to death — but here there’s one, actually two, obvious ways out of the predicament: up to the transport cable or dooooooown to the snowy slopes below. Both are attempted; neither attempt goes well. Also there are wolves for some reason prowling the east coast The tension in all three of these films comes from the breakdown in personal relationships — five people, two people, or three people. Either trust falters, or individual self-preservation takes over, or latent horrible behavior emerges. This is the horror of movies where people are trapped in close quarters. It’s rarely about the threat posited in the trailer or promotional material. And so to our fifth and Final Axiom of Single Location Horror: Human foibles metastasize, usually catastrophically, in confinement.

But we’re not quite done. We have to get even more constrained, the ultimate and final constraint really. Buried from 2010 stars Ryan Reynolds in a coffin. For the whole movie. There are a few other actors, none shown except on a grainy cell phone screen and mostly providing only voice. This, my weary travelers, is the apotheosis of claustrophobia horror. There is not a single shot from outside the coffin. Indeed, there is not a single shot repeated in this film. I’d love to see how it was made, technically. Reynolds here plays an Iraq-based American civilian truck driver who is buried alive in a plot to extract a ransom from the American occupying forces. He is given a Zippo lighter and a Blackberry. We are Reynolds in this film, slowly suffocating both from the diminishing air and eventually from leaking sand. In fact, the sand sluicing into the coffin is almost a literal hour glass. You know time’s up when the coffin fills up. I think it works and perhaps is proof that good storytelling requires only … a good story. No elaborate sets, no hyper-realistic effects, no lore. And maybe that’s a bonus axiom which applies to all film: despite the affordances of modern cinema, ultimately to be successful a film must tell a good story. It’s just that sometimes you have to trap the story in a box in order to realize that.

What’s that? You’re itching to get out? A little stir crazy? May I recommend the following?

- 10 Cloverfield Lane in a doomsday bunker.

- Paranormal Activity in a small house.

- Bug in a motel room.

- 1408 in a hotel room.

- ATM in an enclosed ATM station.

- Panic Room in a home panic room.

- Pontypool in a DJ booth.

- Flightplan and Red Eye both on planes.

- Life on a space station.

- All the train-based horror we discussed on our last journey.

Well that’s it this week. For goodness sake, stretch your legs. Go take a long walk or something. Catch a baseball game. May your confines going forward be nothing but friendly.

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Unfriendly Confines”:

Hell On Wheels

Prefer to listen to this post?

This week our journey isn’t about where we’re going, my tireless travel companions, it’s how.

I’m a train nerd, not quite what is somewhat derisively called a “foamer” (that is, someone who foams at the mouth at the sight of unique rolling stock) more like a casual trainspotter. My grandfather was an engineer on the Burlington Northern railway which is partially how my line ended up in Chicago. Maybe it’s in my blood. And on the subject of blood and trains, this week we’re talking about rail-based horror in a segment called Hell On Wheels. [play train noise ↓]

There’s a pretty compelling argument that one of the first films ever shown to an audience was horror. Or, at least, horrifying. L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, a 50 second strip of gelatin emulsion and silver halide captured by the French Lumière brothers in 1896, shows a steam-belching passenger train pulling in to a station. That’s it, but oh the sensation it caused. New to almost everyone in the attendance, this moving image, this picture literally in motion of a giant train engine heading straight at the audience caused fear, panic, and fleeing to the rear of the room. It’s been called the founding myth of cinema. And it may be just that, a myth, in the sense that it may not strictly speaking have happened, but it’s also mythic in that it has become the primordial, uncontaminated, visceral audience reaction that every filmmaker — especially makers of horror — longs to achieve.

Trains were at the center of early innovation in spooky special effects. Just seven years after the Lumière boys’ train short an unknown filmmaker created its inverse, literally. The Ghost Train from 1903 shows a train coming around a curve and past a stationary camera, but the print is of the negative, a truly novel technique at the time. This spectral train is made even creepier by the insertion of a separate film of the sun and clouds, also in negative so looking like the moon, up in the corner. It’s a minute long, plotless like L’Arrivée, but it shows the beginnings of technical innovation in filmmaking for the express purpose of frightening viewers.

Even if we didn’t have these charming strips of turn-of-the-century transportation, it cannot be denied that filmmakers love trains. They add an aspect of dynamism, can travel through multiple settings in a short period of time, and offer a conveniently constrained storytelling and staging space for filmmakers to work with. More than one director has noted that trains are in fact metaphors for movies. In cinema, unlike literature, the viewer is not in control. The audience — at least in a theater — has to sit back and experience it until it reaches its destination. You may recall the opening moments of Lars Von Trier’s Europa where the visual similarity between the image of a train going over tracks (or overhead) and film running through a projector is made absolutely clear.

Trains were made for horror. Locomotives can be frightening simply because they are loud, powerful machines made of unforgiving metal — sometimes accompanied by fire, smoke, and sparks. Even better, there’s a whole type of train that only lives in dark, damp underground tunnels full of high voltage wires and rails and pizza-stealing rats. Trains often drag along all manner of characters readymade for horror films: drifters, bandits, late-night urban revelers, people brought together from very different walks of life. Even just the presence of trains can turn a place dark. The term “Hell On Wheels” was originally used to describe the shanty towns of sin that would pop up along the route of the workers as they laid the trans-continental railroad from Omaha to Sacramento. Violent, full of drunks and ne’er-do-wells, and temporary enough to be basically lawless these towns were ready-made to become ghost towns as soon as the rail line moved westward.

Travelers, it’s time to move into the main hall of the station, look towards the clacking of the departure flipboard, and review our options today. The rail yard is so full of train-based horror films we’re going to have to shunt most to sidings. Our departures here today will merely represent the breadth of destinations available in the sub-genre. All aboard! Let’s deadhead this itinerary.

Early experiments with film and trains notwithstanding, the genre mostly begins with Horror Express (1972). This is sci-fi horror with a similar premise to The Thing From Another World. An anthropologist brings the frozen body of an ancient human-like creature onto the Trans-Siberian Railway. Of course, it thaws and it’s … not pleased. Among those stalked aboard this express are Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, and Telly Savalas. Horror Express is a must-watch for your itinerary.

Also from 1972 and also starring Sir Christopher — with Donald Pleasance at the height of his career — is Death Line also known as Raw Meat. Turns out, a group of Victorian workers who built the London Underground subway were trapped by a cave-in in 1892 and their descendants still live down there by way of cannibalizing hapless commuters. The movie ends with the sound of the cannibals echoing through the tunnels “Mind the gap!” What’s not to love about that?

Maybe the most important stop on today’s journey is Terror Train (1980) featuring Jamie Lee Curtis in her post-Halloween scream queen bender. The premise is everything you’d want in an 80s slasher. A group of graduating college kids, all of whom participated in a prank-gone-horribly-wrong three years earlier, have a masquerade party on a train trip and are picked off one-by-one by a killer who changes into the costume of each of his latest victims. Look folks, this is the only film David Copperfield ever starred in not as himself. And he gets a sword through the head. Somehow this is pleasing. I have always loved the dynamic between the train staff (all adults) and the passengers (all college kids). Everything about this film works, especially its ending. If you liked Jamie Lee Curtis in a costume party on a train in Trading Places you’re gonna love this. Turns out, there is a sequel called Terror Train 2 made 42 years after the fact, which I have not seen. Travelers, should I get a ticket to ride?

Night Train to Terror (1985), which certainly sounds promising, is an anthology made from three unfinished films shot years earlier. The only thing that makes this a train film is that it is framed by a conversation between God and Satan discussing the fate of passengers on their way to Vegas. These My Dinner With Andre interstitials are accompanied by what can only be described as a pop music video happening on the train at the same time. It was 1985 after all and MTV reigned supreme. God and Satan chatting it up, sure. But everyone knows that passenger service to Vegas ended in 1971. C’mon, people. It is absolutely clear that the segments here were intended for longer run times. There are plot threads that go nowhere, leaving only gore and boobs. Which, maybe that’s your thing. I consider this movie pretty much a train wreck.

What if the movie Hostel but on a train? Well, that’s the premise of Train (2008), three years after Eli Roth’s film. Apparently this was originally intended to be a remake of Terror Train, but it became something utterly different — probably after it saw how much buzz torture porn was getting. The setup is a group of American high school wrestlers on their way to a match in Ukraine who board a train to Odessa. Little do they know that every other passenger on board is a patient awaiting an organ transplant of some kind and the tourists are being harvested for theirs. A jostling train may be fine for torture and dismemberment, but it probably is not great for transplant surgery which is why the third act takes place at the ruins of what looks like a medieval hospital along the route. This is a fun movie, utterly derivative, but suitably gory with a believable final girl played by Thora Birch.

The Midnight Meat Train (2009) is why you really don’t want to take the last train of the night on a line that doesn’t run 24 hours a day. Who knows where that thing ends up? This movie, based on a short story from Clive Barker, stars Bradley Cooper and Leslie Bibb. (Brooke Shields is also in it, for some reason.) Bradley is a photographer trying to solve the case of disappearances in the subway late at night. He eventually discovers that a butcher named Mahogany has been responsible for murdering passengers on the midnight train. And the fact that he is a butcher is important because it isn’t cannibal Victorians living down there, but something far more warped from the mind of Clive Barker. I won’t spoil the ending because I love this film and I hope you do too.

D-Railed (2018) contains so many of my favorite things in a horror movie. It’s set on Halloween. It takes place aboard a train, and it takes place underwater. Mr. Tour Guide, you must be thinking, that’s preposterous! Let me explain. The movie starts with a bunch of folks on one of those candlelight murder mystery outings aboard a train. Then it becomes a heist movie. Then the heist goes wrong and the train crashes into a river and is partially submerged. But see there’s a monster in the water, the bastard child of the Creature from the Black Lagoon and the Marvel symbiote Venom. The hapless passengers eventually make their way out of the sinking train car wherein the film becomes a cabin-in-the-woods slasher . And then in the last of too many acts to follow for an 80 minute movie it becomes a ghost story. However, the kills here are gory and 100% practical. Points for that. Points also for Lance Henriksen’s top-billing paycheck earned for about three minutes of screen time.

Let’s take a special spur line to talk for a moment about Asian train horror. It’s an exceptionally robust sub-sub-genre. My favorite zombie flick of all time has to be Train to Busan (2016) from South Korea. This is a great film, period; it just happens to talk place mostly on a train, in train stations, or in train tunnels. And, unlike many films discussed here, it uses the physical setting — rolling cars on tracks — as part of the plot, not just part of the setting. Like old time westerns where the roof of train cars allows cool chase and showdown vignettes, the actual train to Busan is used creatively and surprisingly. Train to Busan has spawned an animated prequel called Seoul Station, also excellent, and a standalone sequel called Peninsula which I have not seen. Junkrat Train (2021) from China is, well, about a train infested with rats. The more high-minded but no less fun Kisaragi Station (2022) from Japan takes an Internet meme about a fictional, supernatural train station and rolls with it.

When my family and I first moved to Denver we often heard a train whistle in the distance, especially late at night. But here’s the strange thing: there were no rail lines anywhere near where we lived in Denver. We searched for the source of this train whistle for months before eventually giving up and simply saying “well, there goes the ghost train again”. It became oddly comforting. If you like ghost trains too be similarly comforted in knowing that there are at least 19 films (most but not all of which are horror) with this name.

There are loads of horror films that use trains only partially and to great effect — let’s call this intermodal train horror. For example, the final scene of Drag Me to Hell (2009) shows the cursed protagonist, Christine, as she falls onto the tracks ahead of an oncoming train. We’re meant to think that death-by-smooshing is the calamity headed for her, until she realizes in that very moment that her efforts to avoid hell were thwarted — and it comes clawing. Rabid, An American Werewolf in London, Friday the 13th VIII (the one which has 20 minutes in Manhattan), and the original Creep all have great sequences aboard rolling stock.

As noted this review of train-based horror barely makes a dent in the subgenre. Others worth exploring if you have a one-track mind include Beyond The Door III, Snakes on a Train, End of the Line, The Tunnel (reviewed on this show last April), and Ghost Track.

In 2007 I rode a magnetic levitation train called the Transrapid, the world’s first production-grade maglev for transit. It runs from the Shanghai airport to the edge of the city and reaches a maximum speed of 268 MPH. This may be the most scared I have ever been on a train. For one, I was the only passenger in my car, possibly the only passenger on the train. For another, when I worked my way up to the cab at the front of the first car and peered in through the dark glass as we broke 250 MPH, I saw the sole engineer enthusiastically reading a comic book not ever looking at her controls or out the windshield. WTF. But mostly it was the knowledge that a derailment (if that’s the term for magnetic de-coupling) at this speed would never be survivable. Especially so since the entire route is elevated a few stories above grade. A crash of this train would essentially be that of a slow-moving, low-flying airplane. It’s all I could think about. I enjoyed it, I suppose, in the same way that a roller coaster is enjoyable. Might be thrilling, might kill you even without a maniacal killer aboard. Who knows? And maybe that’s why there are so many films in this niche genre: the very thing you’re traveling on is a potential threat.

OK, tourists, it’s the end of the line. Thank you for joining me on our search for the dark at the end of the tunnel. May your movie viewing always find you on the wrong side of the tracks.

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Hell On Wheels”:

Garden of Forking Paths

Prefer to listen to this post?

My traveling compatriots, I know it has been a wearying year of sites and topics, but we can’t let up now. We’re gonna get super lost today. Maps won’t work. Itineraries will be an illogical mess. Today we’re gonna talk about non-linear horror in a segment called The Garden of Forking Paths.

The shortest path is a straight line, right? Probably, if we forget about bizarre quantum behavior and wormholes, but sometimes a line that isn’t straight at all can make for an interesting story. It’s true that the constraints of film — which are produced by someone (or group of someones) controlling the progression of a story which has a discrete beginning and end — make non-linearity difficult and sometimes confusing. Moreover the format of film basically disallows choice or meaningful interactivity from the viewer. But this difficulty, this resistance in the materials so to say, can deliver compelling and often unsettling films. Non-linear storytelling is most common in thrillers and to some extent drama, but it’s the very way that going against convention destabilizes the viewer that makes it perfect for horror, when done well.

The title of our journey today, Garden of Forking Paths, refers to a 1941 short story by Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges (full text here) in which he describes a writer who has created an infinite text which forks off a new story from every single event in his novel. While we don’t have that (in any form of fiction) the internet has, in a way, given us a garden of forking stories, however amateur, in the terabytes of fan-fiction that are spun up extending beloved or cult novels and films. This doesn’t happen as much in horror as in other genres, though it certainly does happen — even sometimes convincing studios to make actual films based on fan concoctions and hoped-for franchise crossovers. Or sometimes fans just take it upon themselves, copyright be damned, to make films out of stories they dream up. For example, the surprisingly good Never Hike Alone, is one of 19 fan-made films listed for Friday the 13th on IMDB. (I struggle and fail not to mention the largely fan-driven Amityville universe, which at the time of this recording, consists of 56 films. This may be the closest we’ll ever get to Borges’ garden, sadly.) The horror-adjacent genre of true crime also spins out dozens of potential storylines by virtue of the fact that these shows often do not have an ending, some of which like Unsolved Mysteries come right out and tell the viewer so. Everyone watching these shows has a theory and amateur sleuths set off on sometimes ludicrous attempts to provide their own narrative conclusion.

But these are all exceptions to traditional filmmaking and you could argue are examples of derivation rather than non-linearity. So what about actual non-linear horror films? OK, travelers, fine, let’s get back on the path — but I told you I’d lose you. The irony is that most films are not shot in a chronological sequence that conforms to time as depicted in the movie. This of course is for logistical, often economic reasons. But my guess is that some directors — in shooting out-of-sequence — are presented with new artistic possibilities of contrast, juxtaposition, or information disclosure that weren’t in the script to begin with. This is just a personal theory. Any listeners out there who direct films, please tell me how wrong I am.

The simplest kind of non-linearity are flashbacks and rewinds. Many horror films contain at least a bit of storytelling purely for backstory purposes. When this is done anywhere but the beginning of the film that’s a flashback. There are too many examples of this to list, but some films use flashback in novel ways. The original Cloverfield, a kind of modern-day Godzilla flick, is presented as the continuous footage from a camcorder the night of the film’s mayhem. The expository flashbacks occur in sequence, though, as they are snippets of home movies previously recorded on the tape that is being recorded over imperfectly the night of the events of the film. It’s quite clever. Many of the Saw franchise, certainly the first, only make sense once the chronological events of the film are decoded via an elaborate narrated flashback at the end of the film. This flashback is a kind of storytelling in reverse, an actual rewind re-interpreting the events you just witnessed through a different frame. The 2002 French film Irréversible by Gaspar Noé presents an entire film in reverse, which of course inverts the audience’s normal sense-making task and expectations. The film follows two men attempting to avenge the rape and beating of the woman they love. It is also one of the most graphically brutal films I’ve ever seen. Two versions of this film exist. The original at 97 minutes and the “straight cut” told in forward chronology at 86 minutes. Having not seen the straight cut I don’t know which 11 minutes were cut out, but it does make me wonder if they contain plot points that are only necessary to avoid complete confusion in the original, reversed telling.

Moving into more complex non-linearity are time travel and time loop-based horror films. Listeners need only loop back one episode in their podcast queue to last week’s Heavy Leather Horror Show for a good example of a horror time loop (played out literally as spatial recursion) in the film Drive Back. Time loops work especially well in comedy and horror, related genres in so many ways, because they give the audience the opportunity to wonder how the next iteration will deviate from the previous. This is a setup for a laugh (in the case of comedy) or a surprise (in the case of horror). Time loopy horror, though, benefits from the very claustrophobia of the conceit. Being trapped in time is no less scary than being trapped in a space. Scarier, in some ways, because at least characters can die trapped in a space; often in time loop tales they can’t even perish, trapped forever in a looping hell of the same events over and over. Another good example in this sub-genre is the film Every Time I Die, “the story of a man, who after being murdered, finds his consciousness transferred to the bodies of his friends and tries to warn and protect them from the killer who previously murdered him at a remote lake.”

This week I watched Triangle a 2009 British piece of non-linear horror that really leans into the intrinsic terror of being caught in a loop which becomes a downward spiral as the realization of helplessness sets in. A single mom named Jess, played by Melissa George, with a fraught relationship with her young autistic son decides reluctantly to go on a sailboat excursion with friends. The boat is capsized by a freak storm and they all cling to its hull until an ocean liner with a single figure on its deck comes by. They board it and things start getting weird. For one, it’s empty except for a hooded figure trying to kill them all with a shotgun. Clocks are not in synch. Everything seems strangely from the 1920s. Eventually Jess figures out it is herself — or a version of herself — with the hood and shotgun and that she’s in a horrible loop. She does eventually escape the boat-based loop only to find that she is in another, more terrifying one. This isn’t a scary movie or a gory movie, but it is psychologically harrowing, especially at the end. Or rather, especially when the movie stops.

The majority of non-linear horror is more difficult to classify. There’s no accepted term for the kind of psychological horror whose narrative logic seems pulled straight from dreams. Let’s call these dreamtime films. Psychedelic, nested, or often completely illogical, these films are more about how they make viewers feel rather than providing a coherent narrative. This is non-linearity not as a storytelling device but as a mood-setting technique. What impressionism is to realism in painting. And it works so well in horror. Just the break with convention can be upsetting to a viewer, forget about jump-scares or blood (though they contain those too, of course). Examples of dream-like non-linearity include: Climax (an even more fucked-up film by Gaspar Noé), In The Mouth of Madness, Jacob’s Ladder, Annihilation, Possession, and Videodrome.

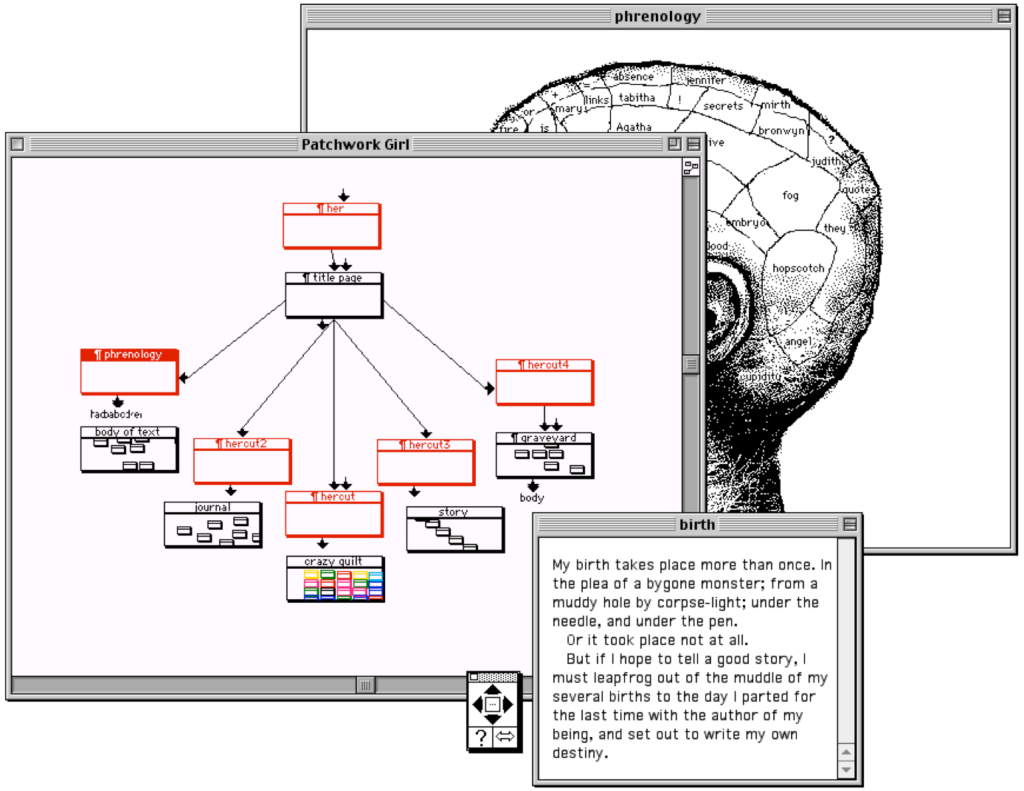

Travelers, let’s stay with horror but step just off the path of film for a moment to talk about true non-linearity, which is to say, interactive storytelling. If you are of a certain age you surely remember the book series from the 80s called Choose Your Own Adventure. These books were presented as literal forking paths where readers would decide what the protagonist should do at various decision points. They were fun, though of course they were finite — an example of what literary theorists call interactive multi-cursal (that is, many paths) storytelling. The reader’s agency was limited of course: go to this page or that page based on a fairly binary choice (i.e., “pick up the hammer” or “pick up the milk carton”). Some of the stories in the original Choose Your Own Adventure were horror tales (like “House of Danger”, “Vampire Express”, and “Ghost Hunter”) and there was even a 90s knockoff called Choose Your Own Nightmare. The niche electronic literature genre known as hypertext has few classics but one of them has to be Shelley Jackson’s 1995 Patchwork Girl, a re-telling of the Frankenstein tale. It’s so much more than that though: what seems like disarticulated scraps of text eventually comes alive, stitched together like the original monster. Being computer-based, Patchwork Girl has sophisticated mechanisms in place for allowing you to continue reading along paths only if certain passages have already been read (or not read). I highly recommend seeking this out. It’s on the platform called Storyspace.

But really interactive horror that would actually frighten someone (and which gave more than yes/no decision-making opportunities) had to wait until video games in the early 2000s. Classic survival horror like Resident Evil pioneered the genre, which would reach its full maturity in titles/franchises such as Silent Hill, House of Ashes, Until Dawn and my personal favorite Dead Space. Indeed many video games today use the same techniques as film — real-world sets containing actors in motion capture suits for instance. And the graphical capabilities of today’s machines make verisimilitude the norm but of course never a constraint.

The question often asked is: can you be truly scared when you’re in control of what happens? My answer is absolutely yes, indeed I am sometimes more frightened playing a horror game than when watching a film. Being disemboweled as a consequence of your own actions is a lot worse, for me, than simply watching someone on the screen dump their guts on the floor. I would even say that I have seen horror gaming as a gateway experience for people who would otherwise never watch a horror movie. The sense of control was enough to get them to play a game but then, having enjoyed it, they sought out horror films.

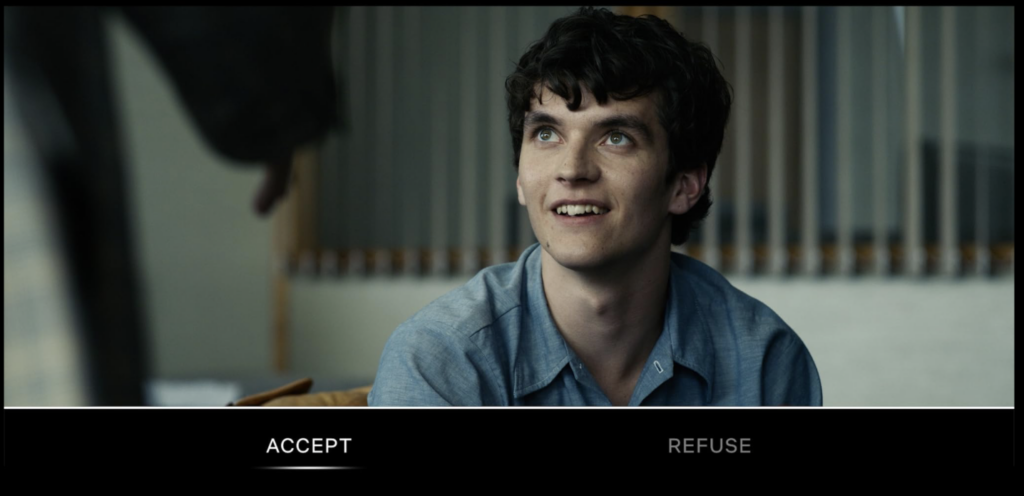

The viewer-in-control aspect of video gaming has even wandered back into film. The 2018 Black Mirror episode called Bandersnatch required new functionality to be built for the Netflix player. The story follows — or at least begins with — a software developer trying to get a game published. You, as viewer, determine the choices he makes. It’s just the right balance of sit-back enjoyment and lean-forward engagement for my taste. The runtime says it is 90 minutes long which may be what happens if you make no choices at all (after 10 seconds the story continues along some default path), but to view everything would take 312 minutes. The shortest possible path to a point called an end is 40 minutes. It’s all live action and, being Black Mirror, quite dark. I do not think Netflix has done anything further with this functionality, but I wish they would.

Previously on this show I have plugged a phone app called Guide Along. It’s meant to tell you about things you are seeing on road trips, often but not always through national parks or exceptionally scenic drives. The key to this app is that the story segments are entirely GPS-based. Wherever you are it tailors the content, even reminding you to drive the speed limit lest you trigger a new story too soon. This is non-linear storytelling too, of course, where it isn’t the viewer’s decisions so much as their literal location that determines the sequence. I don’t think there’s an application for this in horror filmmaking, though there could be in haunted house attractions. If you are an investor and this idea appeals to you please call our hotline at (724) 246-4669.

Well that’s it, travelers. Hope you weren’t too flummoxed by today’s journey. Actually If you’re not confused I did this wrong and I recommend you watch any of the films mentioned here. Until next time, whichever timeline that is!

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Garden of Forking Paths”:

Pied-à-Terror

Prefer to listen to this post?

There is no more important location in horror fiction than the house. The geometry of surfaces that creates an inside where only outside once was, subject to the decay of time like a human body, able to be loved, often to be feared: the haunted house. Tourists, as I speak to you now from a home emptied of the people I love and denuded of the artifacts which made it a place of life, I plot today’s itinerary inside an actual haunted house, haunting at least to me, if not by ghosts, then by memory — which may, frankly, be the same thing. Today we explore the horror of the built environment in a segment I call Pied-à-Terror.

Let’s ask a fundamental question as we begin our journey. Why is so much horror fiction set in houses or other built places of living?

Houses are made for people to live in (as opposed to barns for animals or sheds for storage). There’s a sense that when homes aren’t occupied by people they are at best cold and empty, at worst somehow desirous for other things to move in. We have an urge for homes to be populated, usually by people, and if not then reminders or ghosts of people. They are vessels for living and we want to fill them with something. This is why it is demonstrably more difficult to sell a house that has no signs of life at all (no furniture, etc) than one that is.

Historically, most people have died in their own homes, at least since there has been the concept of a home, and usually they’ve passed away inside bedrooms. Even today some terminally ill people choose hospice inside their homes specifically so that life can end there rather than in a hospital. People who have died — by choice or not — in a home are of course the source of the innumerable ghost tales associated with haunted buildings. We anchor people to location probably more intensely than any other correlative other than smell. (You simply can’t beat smell. Thanks, lizard brain!)

Scientists call this the “sensed-presence effect”, the feeling that there is another person present when there is not. This is explained as a result of monotony, darkness, cold, hunger, fatigue, fear, and/or sleep deprivation. All things that happen to people, especially when alone in a house. Other explanations proffered include hypnagogic hallucinations, restless leg syndrome, and of course very often outright hoaxes. Sometimes it’s the actual decay of a building that is to blame. Carbon monoxide, pesticide, and formaldehyde can lead to hallucinations and have at least on a few occasions been documented as the source of perceived hauntings. Clear up the monoxide leak, no more ghosts.

A poll from almost 20 years ago noted that 37% of Americans, 28% of Canadians, and 40% of Britons believed in haunted houses. I bet the numbers are higher now. But haunted houses are one of the oldest beliefs around. Pliny the Younger, the author from first century Athens, wrote what we think is the first tale of a haunted house, in this case a Greek villa bedeviled by a scraggly, bearded man in chains who really just wanted his bones properly interred.

Haunted houses more recently are, of course, everywhere. They are an entertainment industry totally separate from books and movies, especially around Halloween. And their popularity seems to be increasing: I’ve noticed many temporary haunt attractions just staying up and re-theming as Christmas-inspired haunted spaces. Soon it will never not be haunted house season.

Haunted architecture in horror movies specifically fall into a few categories. Let’s walk through this neighborhood together, tourists. Hold hands if necessary.

Our first stop you’ve visited dozens if not hundreds of times before. It is the traditional haunted house (and its inbred cousin the cabin-in-the-woods). If there is a single icon of horror cinema, it is this — the ornate Gothic or Victorian mansion, usually up on a hill, often in a state of disrepair. The formula varies, but, like obscenity, you know it when you see it: Norman Bates’ house in Psycho, the neoclassical mansion from both Phantasm and Burnt Offerings, the haunted house on a hill in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, New England’s iconic The House by the Cemetery (1981), even the Art Deco castle of the pre-Code blockbuster The Black Cat (1934) — the list is effectively endless. All manner of bad things happen in these houses which are really just dressing on a corpse.

Tourists, let’s take a quick peek down this side street before we get to the next stop. Often what I have called traditional haunted houses are simply creepy locations for the purpose of mood-setting; the threat is something inside (like ghosts) or outside (like home invaders). But sometimes it is the building itself that is the malevolence. Think of the house at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, NY (not to mention that its facade actually looks like a menacing face) or The Overlook Hotel in Kubrick’s take on The Shining, or the outpost dormitory of Robert Eggers’ 2019 The Lighthouse. All of these structures are the antagonists, even while they possess or animate otherwise good people to do very bad things. Put another way, the houses are the source of the misbehavior rather than just the setting for it. This was the twist in Insidious (2010): where all the signs pointed to the home being evil we’re told quite explicitly “It’s not the house that’s haunted”.

One last excursion in this neighborhood if you will: we’re entering the cul-de-sac of suburban horror. The houses in these locales are not exactly terrifying, but their location — in seemingly cozy, safe subdivisions — and their very un-exceptionalism make the horrors they contain that much more disquieting. You probably don’t live in a decrepit castle, but you have at least been in a residential neighborhood. The message in these movies is that the crazy person with the machete will get you either way. Sometimes the very sameness of the homes of suburbia is the scare. Take Vivarium (2019) about a couple who cannot escape — as in, literally cannot find their way out of — the monotony of identical townhouses that make up their community. Poltergeist (1982) was one of the first movies to foreground suburbia as, if not the villain exactly, at least the problem. Developers intent on turning rural land into a planned community place a new home directly above a cemetery, moving only the headstones. It’s a deliberate commentary on suburbia as Steven, the Dad played by Craig T. Nelson, is a real estate agent. Even the original Halloween (1978), set in the fictional community of Haddonfield, places the killer on leafy sidewalks of what would otherwise be the most non-threatening of neighborhoods. In a nod to tradition (maybe), Carpenter used a folk version of a Victorian house for the Strode residence. Suburban homes became such a trend for a while (A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Gate, and countless others) that the first full-throated meta-horror, Scream (1996), was set precisely there.

Our next neighborhood, my tourists, is known for its surreal architecture. Sometimes these Escher-esque places are inhabited by ghosts or monsters, but in all these stories the frightening core — and often the thing that kills — is their spatial disorientation. I have personal experience in this regard. The first office building I worked in, called Wildwood Plaza in Atlanta, was designed by renowned architect I.M. Pei and opened just two years after his pyramid entrance to The Louvre debuted. Like any young idiot new to office culture I could not find my way around, but I later learned this was by design. Pei loved messing with right angles, which is to say, not having them. The halls, ceilings, and many rooms of Wildwood Plaza lacked traditional 90° joints between planes. It was wildly, though not always consciously, confounding. As right angles do not exist in nature, except accidentally, humans have come to rely on them to create orderly, understandable, legible spaces. And when that convenience is missing, we get confused or feel trapped. Which is why illogical or impossible spaces are so prevalent in horror. When characters are disoriented, so are we the viewers.

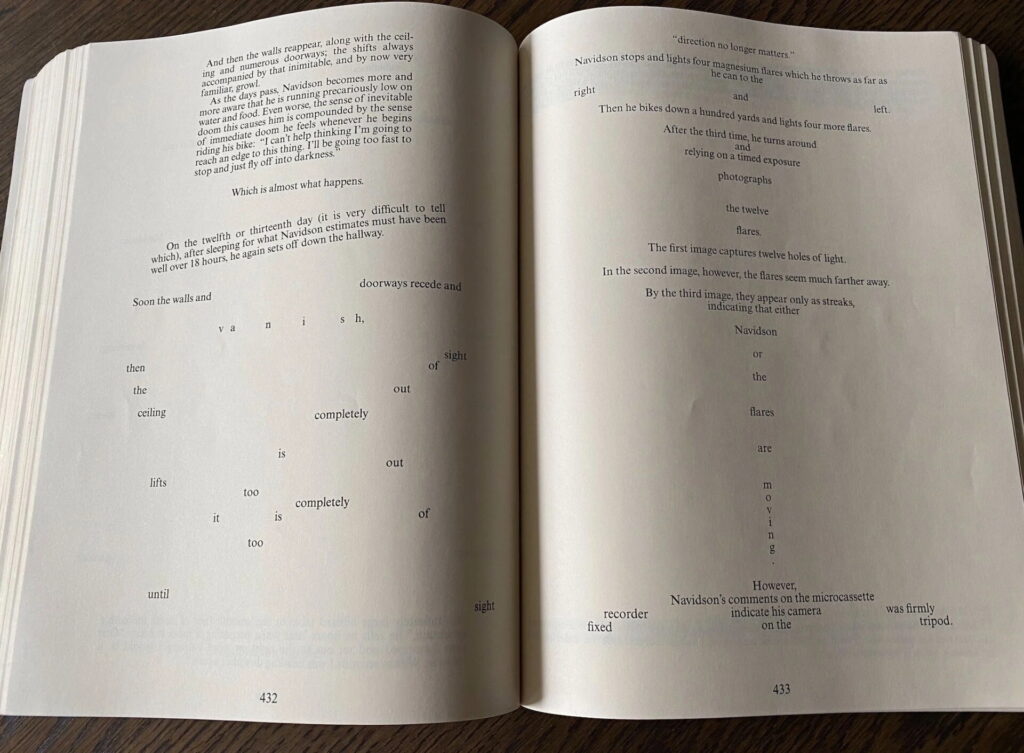

The touchstone of this genre has got to be the book House of Leaves (2000) by Mark Z. Danielewski. To say that House of Leaves is a story-within-a-story is to leave out at least a half-dozen nested stories. But, at root, is a documentary film purporting to show the lives of a family as captured by their in-home camera system. Their house begins to change in very non-Euclidean ways — doors appear were once only walls stood, corridors extend impossibly beyond the house’s exterior envelope, a gigantic seemingly endlessly-descending spiral staircase appears inside a maze at the end of a hallway. The thing about this book, though, is that the writing style and format are simultaneously metafictional, with multiple narrators at cross-purposes, dozens of different typefaces and colors in use, and even pages that require physically rotating the book or reading it reflected in a mirror — all of this is the house-as-maze-like book or maze-like house-as-book. They are both haunted.

Danielewski’s novel has never been made into a film. I’m not sure it could be. But hoo boy would I watch it if it were. (Sidenote for game nerds: there is a Doom mod called MyHouse which was purported to have been created from a simple house map that the creator’s friend, recently deceased, left on a floppy drive. It is very much not that as the house shifts its shape and orientations, just like House of Leaves.)

Cube (1997) is a perfect example of, if not strictly-impossible, then highly improbable architectural horror. It follows five people who find themselves in perfectly square rooms that containing numbered hatches on the floor, the ceiling, and every wall which lead to exactly similar rooms, though each has been separately set with deadly traps. By way of prime number mathematics and, helpfully, learning that one of their cohort was hired to design the outermost shell of the maze, the group devises a plan of escape only to learn that, in fact, the structure is more of a Rubik’s Cube than a static one. The rooms can reconfigure and attach to different rooms. Like the rooms themselves, the movie Cube has led to three other near-duplicates of itself Cube 2: Hypercube, Cube Zero, and a Japanese remake.

Other good examples in this sub-genre include The Platform from 2019 about a vertical prison whose inhabitants are fed by a giant dumbwaiter that drops daily from the topmost floor through 333 levels, leaving the lowermost with nothing but crumbs and gristle, Relic, an Australian film from 2020, where the house of an elderly widow comes to mimic her own dementia, and even to some degree the haunted hotel room film from the Stephen King short story 1408.

Tourists, let’s end our walking tour at some places that deserve special attention. Here are two films that stand out precisely because they are about architecture per se.

The Night House (2020) begins with Beth whose husband, an architect who designed and built the house she lives in, has just committed suicide. One of her friends consoles her saying “You spend so much time with in the same space with someone it’s gonna feel like they are there even when they are not.” If you’re looking for the TL;DR version of this essay on haunted houses, that quote is it. As Beth attempts to deal with her grief she suffers from what seem like hallucinations until she stumbles upon a set of floorpans for a reversed version of her house. Eventually deep in the woods she finds an actual reversed copy of her house filled with ghostly women who look similar to but not exactly like herself.

This film makes great use of literal architecture as the source of fright. There’s a scene where Beth notices that the shadows cast by the moulding atop a basement pillar look unsettlingly like a human silhouette. It’s so clever and well-executed that I missed it, until the shadow moves and I jumped out of my seat. Without spoiling the movie I will say that Owen’s construction of a house-in-reverse is an attempt to fool dark forces out to get Beth who seems to have thwarted their plan for her years ago. The crazy house is actually the solution to the haunting rather than the haunting itself. A very novel take on the trope indeed.

Written and directed by Lars Von Trier and starring Matt Dillon, The House That Jack Built (2018) is a story that hangs off the scaffolding of the structure of Dante’s Inferno. It’s told through a series of flashbacks to the murders of Jack, a wannabe architect and very definite serial killer. The movie contains a narrated dialogue between Jack and Verge (obviously Virgil from Dante) as he descends through his crimes and the nine levels of hell. At one point Jack says “The old cathedrals often have sublime artworks hidden away in the darkest corners for only God to see or whatever. One feels like calling [him] the great architect behind it all. The same goes for murder.”

Throughout the film we’re shown Jack attempting to build his own house from scratch, becoming dissatisfied with his progress, bulldozing it, and starting anew. Meanwhile he’s still killing, often disgustingly so. The movie’s climax takes place in the freezer where he keeps all the corpses of his victims. Verge appears, no longer just an overdubbed narrator, and reminds Jack that he’s never been able to complete his house between all the murders. So, improvising, he arranges all the dead bodies into the shape of a house. It’s a very disturbing image. Jack and Verge enter the house and drop down through a hole in the floor just as police are cutting their way into the freezer. I won’t spoil the epilogue, but if you know Dante you know how this ends. Ironically it is the failure of architecture — in this case a collapsed bridge across the River Styx — that plays a fateful role for Jack.

Of note, this is very long for a horror movie. Over 2.5 hours. Probably could have used a heavy-handed editor and would have been a fine flick without the Inferno metatext and frequent digressions into William Blake, Albert Speer, and others, but I don’t fault its ambition and it does not bore. Of note, there’s brief but very hard-to-watch animal cruelty in one flashback. (It’s CGI, but still.)

A poll from a few years ago found that 64% of people surveyed prefer to watch horror at home rather than in a theater. For movies of all genres the percentage of people who prefer to watch at home drops to 55%. Of course the theater is a different experience entirely (immersive visuals, superior sound, communal experience), but maybe the 9% point difference is meaningful. Maybe there’s something about being scared in the comfort and safety of your house which adds to the allure of horror movies. Is it possible that for that 90 minutes we enjoy living in our very own haunted house?

OK tourists, I hope you enjoyed our excursion today. Time to go home. May I suggest putting on a scary movie?

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Pied-à-Terror”:

Undead Mockingbird

Prefer to listen to this post?

“It’s a sin to kill a mockingbird,” we’re told by Atticus Finch, in the novel title-dropped in that line. Now, think back to your 8th grade self and try to remember why it’s a sin in his opinion. It isn’t because it’s a pretty bird; Atticus says flatly “Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit ʼem”. Anyone remember? It’s because, as Atticus says, they “don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy”. They are, in other words, innocent. And the potential execution of an innocent person is what the book and movie are all about. The story is also about rape, racism, rabid animals, murder, an attack after a Halloween pageant, and a creepy recluse in a house named Boo. Despite this, no one would argue that To Kill a Mockingbird is horror story. But it is a prime example of Southern Gothic, a sub-genre that is full of the grotesque, macabre, and often supernatural and which, as we will explore on our journey today, easily slides into full-blown horror.

Welcome to this week’s itinerary, travelers, called Undead Mockingbird. Grab a sweet ice tea with lemon to go because we’re headed south of the Mason-Dixon line to a land where I went to school, twice, on purpose. And it changed me forever.

Before we arrive at the destination that is Southern Gothic Horror we should probably hit a few waypoints for the terms that comprise it. Let’s start with “gothic”, since, as terror tourists, you’ve likely encountered movies that are utterly suffused with gothic ambiance and tropes. Now, unless we’re talking about the extinct Germanic language of the 5th century Goth peoples or trying to describe why you borrowed your sister’s eyeliner to go to the Siouxsie and the Banshees show — neither of which we are talking about — then we’re talking about a style of architecture.

Gothic building design was a European architecture of the 12th to 16th centuries. You’ve seen it: pointed arches instead of curved domes, flying buttresses that meant walls could for the first time do things — like hold stained glass — instead of solely making sure the roof didn’t fall in, and elaborate ornamental stonework of all kinds including, yes, gargoyles. If you can picture Notre Dame in Paris or the Duomo in Milan then you know exactly what Gothic architecture is. Importantly the term “gothic” was originally applied to this form of architecture as an insult. Artists centuries later considered these buildings to be barbarous, monstrous even, precisely because they were so different from the classical curves of the ancient Greeks and Romans that the Renaissance so eagerly sought to revive.

So, the term “gothic” was originally used with contempt. But it was also applied to very old structures, many in states of decay and ruination by the time of the Renaissance. These buildings — many of which were churches — were equal parts beautiful and rotting, isolated and grandiose, and were the primary inspiration for the gothic fiction of the 18th and 19th centuries. Many of these stories, the first of which is The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole from 1764, take place in gloomy landscapes and/or outright haunted manors. And the people in these places, well, they tend towards the end of the emotional spectrum where rage, lust, madness, and terror dwell. Think of the tales of Edgar Allen Poe, Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley, Charlotte Brontë, and Oscar Wilde.

Gothic fiction was the beginning of the horror genre as we know it. The aesthetic of mystery, of decay, of the past forcing its way into the present (sometimes supernaturally) so defined what in the West would visually be considered scary that most of the costumes you see today at Halloween are just riffs on old gothic motifs. OK so just glancing back at our map: gothic architecture, specifically the buildings of that style in a state of decay, inspired gothic fiction which itself eventually morphed into the larger category of horror fiction.

So how does Southern Gothic, a distinctly American art form, come from what was primarily a European genre? Where the rotting hulks of churches inspired the gothic authors of Europe, the dilapidation of once-majestic plantation houses in the post-Civil War South became a focal point for authors in America seeking to explore themes of a flawed society trying to rebuild itself. These flaws, often personified by grotesque or mysterious figures (like Boo Radley from To Kill A Mockingbird), usually involve racism, violence, and religious extremism — even hoodoo and voodoo.

The characters in Southern Gothic fiction are often physically or psychologically twisted – shut-ins, freaks, back-woods types and those unable to move forward in tight-knit communities, sometimes too tight. These characters, caricatures really, are usually colored — and color is key in this genre — by the dark events of the past, the violent history of race relations, the resentment of Civil War defeat, the Great Depression and, more recently, the devastation of Hurricane Katrina.

Whether overt or as subtext the point of a Southern Gothic story is to reckon with — if not fully rewrite — the myth that the pre-Civil War south was an idyllic, harmonious, and happy time and place. It is, like gothic literature, an attempt to deal with a society in ruin. Authors who wrote in this style at least some of the time include William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty and more recently Anne Rice and (one of my favorite authors) Donna Tartt.

Tourists, you may see where we’re headed. It is not such a leap from the dark themes of these Southern novelists to straight-up horror: mansions rotting into swamps, snake-handling preachers, and unreconstructed beliefs in the supernatural. Southern Gothic often becomes Southern Gothic horror and nowhere is this more true than at the movies.

Before we talk about films, though, a quick note on genre slippage. Categories are always tricky; what’s the real difference between a dark thriller and a horror movie with a gore score of zero, for example? But in the case of the category of Southern Gothic we’re actually taking about a geographical place, specifically the states of the former Confederacy. There are many films which you might otherwise call Southern Gothic except for their setting in the American Midwest or amongst the hillbillies of Appalachia. And many of these films are wonderful — see especially The Night of the Hunter from 1955 about a serial killer posing as a preacher in West Virginia or the 2017 film 1922 based on the Stephen King novella about murder and guilt on a Nebraska farm. But for now let’s constrain our travels to the South and a few standout films.

Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte is a 1964 creep-out starring Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland as middle-aged cousins in Louisiana attempting to keep the local authorities from demolishing a home in the path of a new interstate. That’d make for a pretty good straight drama, except that Bette is also the primary suspect in the decades-old unsolved murder of her former lover whose decapitated head comes back for a visit. Of note, this film is 133 minutes long and very slow by contemporary pacing standards, but it is a great example of the subgenre.

The masterful director Lucio Fulci wasn’t afraid of trying anything and his film The Beyond from 1981 is his take on Southern Gothic. Filmed on location in and around New Orleans, The Beyond is about a woman, Liza, who inherits and attempts to rehabilitate a crumbling old hotel — which happens to be sitting atop one of the seven gates of hell! This is an exceptional film, part of the Fulci’s Gates of Hell trilogy, one of the UK’s “video nasties”, and did not see an uncut release in the US until 1998. You need to see this film not only because of its contribution to our subject today but because the ending is bleak as all hell — er, as all beyond.

Angel Heart from 1987 is a noir-ish detective tale with a satantic twist. This film partakes of lots of Southern Gothic tropes aesthetically, but does include one we haven’t mentioned yet, the half-crazed war veteran. In this case it’s not a Civil War veteran but an injured WWII solider who’s gone missing. A man named Louis Cyphre, played by De Niro, hires a private investigator named Harry Angel, played by Mickey Rourke, to find the veteran who owes him a debt. It’s a fallen angel tale set amidst the dark, oppressively humid decadence of New Orleans.

And if Big Easy decadence is your thing then you’re likely a fan of the novels of Anne Rice about the vampire Lestat. Interview with the Vampire from 1994 is the big budget film version of the novel of the same name, featuring Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt, Antonio Banderas and a young Kirsten Dunst. Much of the film takes place in antebellum Louisiana with all its Caribbean disease, rotten swamps, wrought iron balconies, and candle-lit passages. It’s ultimately a tale of child murder — or at least, taking the human life from a child — and the grief surrounding this act. But it’s also a very modern take on the visual trappings of southern-inflected horror. I suggest reading the books and skipping the movie, but hey you do you.

If you want the Cliffs Notes version of Southern Gothic have a watch of The Skeleton Key featuring Kate Hudson and John Hurt from 2005. This film contains every possible Southern Gothic trope (or cliche, if you’re feeling critical): a plantation house in the middle of a rural parish in Louisiana, the twisted legacy of a slave lynching, hoodoo rituals, and all the atmosphere of a once-majestic society now covered in a layer of dust. It’s not a perfect film, but it may be the most exemplary of our genre exploration.

Is there such a thing as a Southern Gothic slasher? Indeed there is, my touring pals. It’s called Hatchet from 2006 and features the undead, deformed Victor Crowley who slops through swamps in search of his next victims. In this case it’s a group of tourists (just like us!) stranded in the countryside on a ghost tour out of New Orleans. Hatchet is paint-by-numbers horror — you know exactly what you’re going to get and pretty much exactly where its going, but at the time I enjoyed the fresh setting and I found it fun to see how southern motifs were woven into the scaffolding pulled mostly from 1980s campground horror. There are several more Crowley films after this one, if this is your jam.

A House on the Bayou from 2021, reviewed on this pod previously, is an unexpected entry in the genre, focusing primarily on familial tension over an affair but set in a decaying mansion in the swampy countryside. The family here are outsiders, definitely not southerners, who basically represent us, the viewers, thrust into a world out of time, complete with creepy fellows named Grandpappy who represent the old order, the way things used to be but which definitely shouldn’t be. Great performances and an excellent twist!

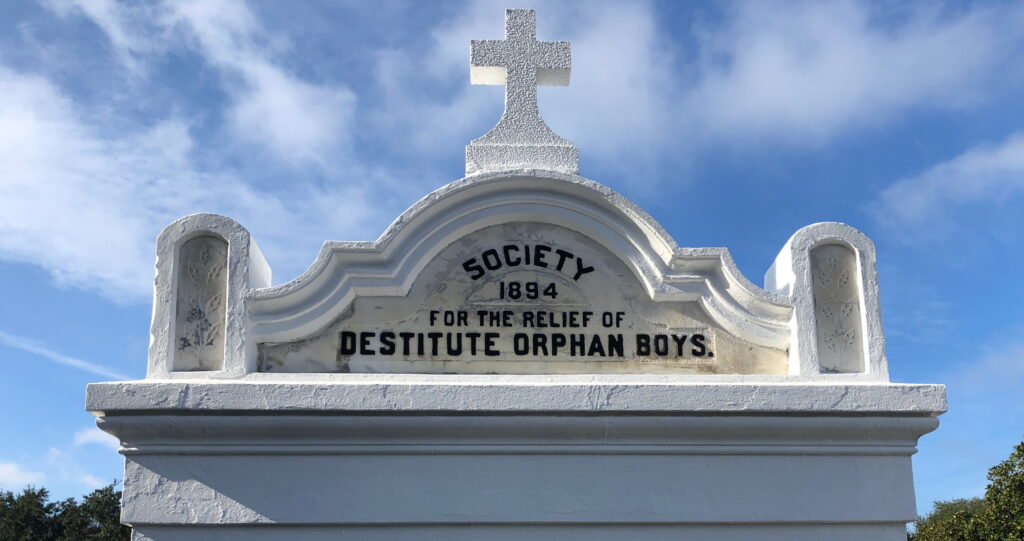

Now, you may have noticed something about all these films. I chose them almost randomly — a few I had seen previously, a few I had wanted to see — as exemplars of Southern Gothic horror. But every single one of them is set in Louisiana, often New Orleans. This isn’t coincidence. Louisiana is ground zero for the genre, possibly because it has the most visible legacy of majesty-in-ruin, colliding cultures of decadence and religiosity, diverse peoples mixing uneasily (black and white, high society and low, European and Afro-Caribbean colonizers and immigrants), all stewing in an oppressive climate of bugs, alligators, and slithering creatures.

I haven’t done an exhaustive census, but my guess is that more than half of what you’d consider quintessential Southern Gothic Horror takes place in Louisiana. Yes there are films which do not — of special note is Cape Fear, both the 1962 and 1991 versions, set on the outer banks of North Carolina. But the center of gravity for the genre seems always to be the Deep South. The entire third season of American Horror Story, called Coven, is set amongst the witches of New Orleans, for instance. Of note, my wife is from New Orleans. Is she a southern goth witch? This is an exploration for a possible future installment of The Terror Tourist.

Until then, my compatriots, sorry for the humidity. And the mosquitos. But hey, we enjoyed some lovely sweet ice tea, no? See you on our next journey!

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Undead Mockingbird”:

End Quote

Prefer to listen to this post?

The End. Fin. Game Over.

We begin our journey today, tourists, at the very end. Cliche be damned: it isn’t the journey; it isn’t the people you meet along the way; it’s the destination. And that destination almost always is death. In the horror genre this is obvious — character deaths are usually dramatic fulcrums, sometimes moments of novelty, and often outright astonishing.

But the end in film is so much more powerful than death. We watch movies in part because they end. We know the story is finite and must draw to some conclusion and that conclusion is usually hinted at before we even start. There’s a satisfaction in that, a satisfaction that often eludes us in the real world. Usually we don’t have answers to: How will we end? How will the world end? Are we humans a 90 minute hangout film or a multi-part saga? Do we come back for a sequel?

Welcome to today’s Terror Tourist itinerary called “End Quote”.

Human death is as varied as human life, of course, and is the subject of the vast majority of films across all genres — whether explicit (as in horror) or as a unstated complement or antagonist to the will to live and love (as in romantic comedies). So, yeah, human mortality is the engine of all fiction. But all the different ways people die is an journey too lengthy for us today, travelers.

Instead, let’s consider the end of everything. Apocalypse. Ragnarök. Doomsday. How humans behave in the face of worldwide annihilation is often as dramatically interesting as how they face their own ends. Which is why the theme of apocalypse is everywhere in films — from horror to thrillers to superhero movies to comedy.

When we talk about the apocalypse we usually mean the end of life, specifically. There have been five near-total apocalypses in the history of planet earth. (We discussed the most recent of these — the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs — on our Terrible Lizards journey.) Almost all of these near-extinctions were caused by some kind of naturally-induced warming or deoxygenation of the planet. And this is why many scientists believe we are in a sixth extinction event, the only one caused specifically by humans as we have moved carbon safely stored in the ground and have thrown it into the atmosphere, trapping heat and warming our rock beyond the parameters in which life thrives. Fiction, especially in the last decade, has often made the existential threat of climate change its main or at least secondary theme.

But climate change isn’t the only way it all ends. There’s asteroid impact. We know that happens. In 2016 NASA established the Planetary Defense Coordination Office to track potential impact hazards. There are gamma ray bursts coming from far away in the galaxy. This radiation which comes from violently-exploding stars called supernovae would strip away our ozone layer, which I suppose brings us straight back to climate change. Without the sunscreen of ozone life just burns up. Speaking of the sun, that ball of plasma could be our end too — if we make it long enough. As our sun ages and dies it will swell in size and intensity, swallowing Mercury and Venus, irradiating and heating Earth well beyond what life can tolerate. (It may even swallow us whole too before petering out. Impossible to know, but again we’d be long gone before that happened.)

Film sometimes deals with these kinds of natural disaster earthly ends, but more often than not the subject is human-centric apocalypse — most recently viral pandemics. Indeed one way to categorize the history of horror cinema is to look at what threat currently dominates the public imagination. Alien invasion, robots run amok, beasts mutated from atomic radiation, zombies, werewolves, and vampires (which as often as not are stand-ins for some other fear or threat), nuclear annihilation, artificial intelligence that comes to oppose biological intelligence. (We’re about to get a lot of those.)

But what about everything everything. As in the universe itself. Well, compatriots, this is where it gets really weird and little bit scary. There’s a branch of physics that deals with the ultimate fate of the universe. It’s quite a vibrant and not at all morose field of inquiry.

Basically there are four possibilities for how it all ends:

The Big Freeze (also known as Heat Death) is the one that has the most support amongst physicists. We’re coming up on about a century since ol’ Edwin Hubble calculated a cosmological constant which tells us how fast the universe is expanding from the cataclysm that started it all, the Big Bang. And it definitely, provably is expanding (in fact, it’s accelerating which is so bizarre we had to make up an undetected force — dark energy — even to explain it). Everything in the universe seems to be expanding away from everything else as if it all — planets, galaxies, you, me, your cat, that hot dog over there — were all on the surface of a balloon that was expanding. So why is this called the Big Freeze? Well eventually everything will be so far apart that gravitational attraction will no longer bring matter into contact with other matter, so there will be no reactions that give rise to stars. And without stars, well, you get a heat death. The opposite of the Big Bang is indeed a whimper. Dark, cold, and nothing. Everybody dies.

The Big Crunch is the opposite. The idea here is that, yes, everything is expanding, but eventually gravity will win and halt the outward movement. In fact, eventually everything will pull back in closer and closer until it all smooshes down into a dimensionless singularity. Everybody dies.

The Big Bounce is just an endlessly repeating cycle of Big Freezes and Big Crunches, based on the assumption that a dimensionless singularity of all the matter in the universe would then explode (Big Bang-style). This seems to run afoul of quantum mechanics, but the truth is we really have no idea what happened at the very moment of the Big Bang. Everybody dies. Maybe life comes back. But everybody dies again if they do.

Now here’s the scary one: The Big Rip. I mentioned that the universe’s expansion is accelerating and that we don’t really know why. But we do know that the acceleration is constant, which we should be glad for because that constant is just fast enough to expand but not fast enough to destroy local structures like galaxies or stars or us humans. But … technically there’s no reason that the acceleration must stay constant. If it increases (because, for instance, dark matter and dark energy are weirder than we even think) it could be curtains for everything down to individual atoms. The distance between particles themselves would become infinite in a finite amount of time. Riiiiiiiiiiip. The ultimate explosion. Everybody dies.

Apocalypse has been a subject of film since the very beginning. We are lucky to have a restored copy of the Danish film Verdens Undergang (literally “The End of the World”) from 1916. While this is science fiction rather than what we would come to call horror, it definitely points the way. Natural disaster, panic, and general mayhem ensue after a comet passes Earth. And the audience was ready for this having just witnessed Halley’s Comet in 1910 and being in the middle of a world war and global influenza pandemic. Horror movies as a mirror of a society’s fears, even way back at the dawn of movies.

Since then the end of the world has diversified.

You’ve got religious, specifically Christian usually Catholic, apocalypse in films like Legion from 2010, starring Paul Bettany as the Archangel Michael. God has had it up to here with humans and so he sends hordes of angels , including the archangel Michael, to eradicate the human race. Michael goes against God’s willing and finds a pregnant woman in a diner whose child will be the savior of mankind. War ensues. The Archangel Gabriel comes down to battle. I liked this film, especially as it begins with Michael cutting his own wings off to blend in with humans.

Then there’s worldwide apocalypse from the undead. Obviously there are hundreds if not thousands of zombie films but only a minority focus on the zombie infestation as a worldwide phenomenon. I mean, it ain’t an apocalypse if it’s just a few shamblers in your local cemetery. George Romero ultimately produced a series of six films starting with Night of the Living Dead that does slowly show the evolution of a global zombie outbreak. This all concludes in the book The Living Dead completed and published posthumously by Romero’s estate that does a wonderful job of carrying the zombie apocalypse to its logical conclusion (spoiler: all flesh, even undead flesh, rots away to nothing). Other good examples of zombies through a global lens are World War Z from 2013 and the 28 Days Later franchise begun in 2002. (28 Years Later is slated for release next year.)

There’s no lack of pandemic virus movies that wipe out humanity, especially these days. We discussed the movie Black Death on our last Terror Tourist jaunt, but there’s also the under-loved Carriers from 2009 starring Chris Pine early in his career. The pathogen in this film is literally called “The World Ender Virus”. No one seems to be sheltering at home — it’s all a bit of a survivalist wasteland — and really no one wears masks. There’s a serum, but apparently it doesn’t work. Maybe this is where Covid would have ended up if the mortality rate was significantly higher.