In which I offer a series of exciting thoughts on punctuation in the 21st century

Just finished a delightful little book on punctuation. No, really I did. The central theme of the book — hey, you should care about punctuation because, if you don’t, what you mean to say can run off the rails — is made through a variety of humorous reflections on individual punctuation marks. (The author, Lynne Truss, would have a real problem with my use of the dashes above, for instance. And probably my love affair with the parenthesis for that matter.)

The final chapter deals with the effects of computer-mediated communication and the Internet on punctuation usage. As you’d guess, she’s not impressed.

Anyone interested in punctuation has a dual reason to feel aggrieved about smileys, because not only are they a paltry substitute for expressing oneself properly; they are also designed by people who evidently thought the punctuation marks on the standard keyboard cried out for an ornamental function. What’s this dot-on-top-of-a-dot thing for? What earthly good is it? Well, if you look at it sideways, it could be a pair of eyes.

Clearly the emoticon is less like punctuation and more a crude surrogate for emotive language. But I think there is one aspect of computer-based writing that does deserve consideration as a new kind of punctuation: the hyperlink. By those who love the link it is usually treated as a technical feature or a design aspect. To those decrying the end of the book (and thus the end of critical thinking and thus the end of civilization) it is seen as a roadblock to sustained argument and reason. But people get too hung up on the fact that the link leads somewhere. In fact, the hyperlink really does act like punctuation, regardless of where the link takes you.

Consider how many links you encounter in prose that you do not click. Hundreds if not thousands daily. Clearly they change the structure of the sentence, whether you click on them or not. So what is the effect, from a punctuation perspective, of the unclicked link? Well, it isn’t a pause or a full stop so that means it isn’t like a comma, semi-colon, or period. (Stay with me people, this is interesting.) Assuming it is visually different from normal text, the unclicked link is more akin to a colon whose job it is to introduce some thought clearly related to what precedes it. Truss describes it so:

… [the colon] rather theatrically announcnes what is to come. Like a well-trained magician’s assistant, it pauses slightly to give you time to get a bit worried, and then efficiently whisks away the cloth and reveals the trick complete.

The link is a multi-dimensional colon. Oh, it announces what’s to come alright, but what’s to come doesn’t exist on the same plane as what you were just reading.

The link also performs a role similar to parentheses, brackets, em-dashes, and even quotation marks. The unclicked link, in short, suggests structured meaning in prose without actually conveying an idea the way words do — which of course is exactly what punctuation does. You might say, well the link is just a fancy kind of footnote. But that too focuses too much on the function of the footnote after you’ve followed it where it leads and not on how it operates semantically in the context of the sentence. The footnote superscript is punctuative (whoa, Googlewhack candidate alert) in that it says “hey, this is important enough to require commentary.” Even if you don’t travel down the page or to the endnotes this extra bit of meaning has been conveyed by the superscript. Same with the link. It is a call-out, evidence however slight that there’s elaboration, example, or extra material nearby.

In his book Interface Culture, Steven Johnson noted the unique use of links by the now-defunct Suck site. I’d argue that the best linking on the web today has mostly caught up with the style pioneered by Suck.

The rest of the Web saw hypertext as an electrified table of contents, or a supply of steroid-addled footnotes. The Sucksters saw it as a way of phrasing a thought. They stitched links into the fabric of their sentence, like an adjective vamping up a noun, or a parenthetical clause that conveys a sense of unease with the main premise of the sentence. They didn’t bother with the usual conventions of “further reading”; they weren’t linking to the interactive discussions among their readers; and they certainly weren’t building hypertext “environments”. … Instead, they used links like modifiers, like punctuation – something hardwired into the sentence itself.

What it comes down to is only this: I am getting to the point where I don’t trust online writing that does not contain links. Just like you’re wary of the grocer who sells “apple’s” or the the writer whose sentences run on for miles without a period, I’m increasingly uncomfortable with writing that’s link-free. I may never click the links I encounter, but their presence indicates a structuring of thought that subtly affects how I approach what I am reading. Just like punctuation.

Vanity googling

One of my resolutions in January was to find my roommate from study abroad in Rome in 1993. I listed his name hoping that it’d get indexed and that at some time in the future he’d Google himself and find that I was looking for him. This is exactly what happened. Some people feel self-conscious about Googling themselves, which is crazy. It is the one sure bet you can make: people will Google their own names (and download naughty things, I suppose). This behavior is so natural that if you have your name on a page with another’s name you can be fairly certain the other will see it at some point in the future. Sort of like posting a note for a person to find out in the wilderness. But found it will be, eventually.

Can you tell what photos of a fan-powered Santa, a stumped computer-user, a truckload of anchovies, and middle-aged Swedes dancing the night away have in common?

They are all returned as image results when Googling my last name. Now, I’ve known for a while that my last name is Icelandic for ‘computer,’ but a majority of the images are of construction equipment or bizarre machinery. The Santa hoverpack? No idea.

Think of it as visual tagging or reverse-steganography. Instead of embedding a secret word in images, you deduce the word from the images themselves. What would be great is a Google image upload feature (akin to typing a keyword) that matched submissions against the database and provided you with shared keyword terms.

Flickr has a tag game sorta like this.

Engineer

Got a Christmas card from some colleagues in Egypt on my return to the office today. It was addressed to Eng. John Tolva. Eng. for Engineer, an honorific I’ve never seen in the West but which is always given in Egypt to (I think) graduates of science-related or engineering-related programs. I like this. It seems more logical to award prefixes based on the type of degree than the level attained, doesn’t it? Imagine a world where everyone was addressed by the job or role they performed.

“Bricklayer Jones, so nice to see you today!”

“You as well, Seamstress Diaz! Say, here comes Ambulance Chaser Franklin.”

There’s a certain LEGOland quality to the division of labor and labelling, but I think I could like it.

To create an aquifer

My father wants to add a word to the Oxford English Dictionary. Now, I love my parents very much so I mean no disrespect when I say that language is not their strong suit. They’ve been making up words for as long as I’ve known them — but they don’t know they are making up words. For example, my mom calls me an “aggravant” which is like an irritant who aggravates. Great word, but not in the dictionary of course.

Only recently has my dad gotten the bee in his bonnet to actually get one of his neologisms into the OED. Poor guy. He doesn’t realize you can’t just write the editor a letter to petition for inclusion. Here’s an excerpt of his submission:

The word is “acquifier”. It means “the process of acquifying”. It is used in governmental and scientific writings to refer to the material comprising the “acquifer” and / or performing “the process of acquifying”. Unfortunately, it is believed by some that the only acceptable word is “acquifer”. But, “acquifer” refers to a specific area or place (frequently a proper noun) rather than the afore stated material and / or process.

Essentially what he is asking for is a word for the process of the creation of an aquifer. The problem is that “aquifier” implies that there is a process called aquifying and it suggests that there is an agent of this aquifying (the “aquifier”). I am not sure this is the case. What is the agent? Water itself? But the real problem is that, unlike the word police French, American lexicographers don’t just add words. New additions have to be proven to be in common usage.

So let me take a moment to state officially that Ascent Stage does not use nor does it support the usage by others of the word “aquifier.”

Spam of the day

“Smith & Wesson: The original point and click interface.”

Made me laugh. If only computers were as easy as guns, you know? You can pry my computer from my cold dead hand.

Lingualism

Real time translation in a conference setting always amazes me. The translators in their claustrophobic boxes have to keep up with nervous, mumbly presenters whose language is often specialized or vague. I try to make it a point to thank whoever has the misfortune of translating me. But it is such a great service. Sometimes I think about how life-changing it would be to have this device all the time. I have, in fact, walked out of a conference hall with the headset on and momentarily forgotten that it is not a Universal Translator that will work anywhere. Darn.

The movie The Red Violin is the first I have seen that moves smoothly and rapidly between many different languages, five in this case. Just when you’ve disabled the subtitles in an English section you’re thrown back into German or Chinese and you have to turn them on again. Thankfully toggling DVD subtitling, especially on a laptop, is painless. (Though it would be nice to be able to say “if any language other than X is being spoken I need subtitles.”)

Which brings me to website design. Multilingual sites — which should be every site but for obvious practical reasons cannot be — must work just as the translator headset or as DVD subtitles work. There should be complete symmetry in all languages and minimal design variation so that a lateral flitting from one to the other is seamless in every regard, except that the language changes — just like switching channels or subtitles. Wikipedia famously achieves this. Eternal Egypt is based on this premise too. In effect what you create this way is a single site with multiple languages, rather than multiple language sites for the same content.

One big ass text file

Recently I successfully migrated most of my personal information apps (calendar, mail, addresses) to a new system. The only thing the new setup lacked was a way to keep track of the hundreds of scraps of information (password, registration codes, etc.) that I had previously kept in Outlook’s cumbersome Notes. Like the other aspects of my personal info I wanted local access with complete online redundancy. Nothing seemed to fit the bill. Then I came across this post at 43 Folders describing über-geeks who actually put all their information into a single, gigantic text file. I laughed at this as completely impractical and moved on.

But I kept thinking about it, specifically about the actual difference between hundreds of tiny files and one huge file. In both cases search is the only practical way to find anything. But a single file reduces redundancy to the act of merely uploading the file ocassionally. And ASCII is the ultimate cross-platform, app-neutral, read-anywhere format. As long as you have a good text editor, you’ll be fine. But even if you don’t you can always at least open the file and roam around. Call it the toilet paper roll method of info management.

Mark thinks Tinderbox is a better solution. I’ll give that a spin when the Windows version is released. But, for now, my life happens inside a single unnavigable-except-for-search text file. Restaurant notes, aborted blog posts, credit card info, SMTP server information from seven years ago, words I like, a Blackjack cheat sheet, domains I’d like to own one day, hundreds of pairs of login info, and on and on. It is stranegly comforting to know that it is all in there, including stuff I will never see again because I don’t know the keywords for it. But it is there.

Sweet language

I met Rabbi Marvin Hier, founder of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, last week. He was describing the new Museum of Tolerance to be built in Jerusalem. It is, in part, a learning center and so in describing the philosophy behind the center’s outreach he used an analogy from a tradition in teaching the Hebrew alphabet. When first encountering the alphabet Jewish children have a drop of honey placed on their tongue as they pronounce the first letter, the aleph. This is meant to equate learning — perhaps language too — with sweetness.

Honey on the Aleph. This I like a lot.

Colorful language

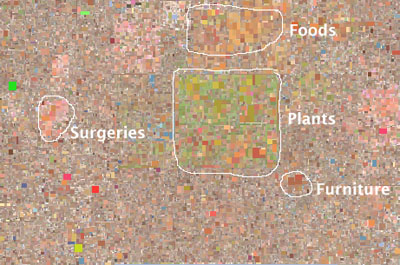

Data visualization master and Most Admired Colleague Martin Wattenberg has created a new info map. Color Code takes English nouns and represents them using the color average of corresponding images of that noun found on the web via Yahoo. Interesting how earth-toned nouns are, but then I suppose much of what we name is human or organic. Yes, all your favorite sexual nouns are included. Yes they are fleshy.

A great extension of this would be to infer colors for verbs based on the images of nouns that the verbs most often operate on. For example, the verb “to fly” might be bluish because of its association with the sky and because the machines that do fly are often colored similarly.

Decompile

Sentence diagramming. Man, did I love sentence diagramming. I can almost hear Sister Bernadette, my obese, structuralist 7th grade teacher, coming up with ever-obscurer sentences to slice-and-dice. It is so out of vogue to teach sentence diagramming now. I’m not even sure they teach the parts of speech anymore. This is a shame. Diagramming was like a game, a kind of puzzle where you were forcing organic, fungible elements of language into a Cartesian, controllable structure. Diagramming a sentence was like decompiling a program, with similar messiness. There are tools now, but nothing beats the one-on-one encounter with a hellishly convoluted syntax:

All this … the reader must enter into before he can comprehend the unimaginable horror which these dreams of oriental imagery and mythological tortures impressed upon me.

Never heard of sentence diagramming? I know some people similarly handicapped. Read up at Wikipedia.