From City work to city work

Pleased to announce that I have recently joined PositivEnergy Practice as its president. PEP, as it is known, is a small engineering firm in Chicago that does big things — as in really tall and very complicated things.

I’m leading a group of talented engineers who design (and re-design) buildings, districts and cities. PEP’s speciality is high-performance, clean tech engineering focused on new structures, retrofits, and urban ecologies of infrastructure. Much of our work is done for — or in partnership with — architecture firms.

Exciting times, these. The tools of data analytics (and the open data itself pouring out of many cities) make this an optimal moment to bring performance simulation to a new level. Likewise, as devices and sensors proliferate throughout our urban areas design and engineering firms — who already understand complex physical systems and the human needs of the spaces they engineer — are well-positioned to potentially remake the notion of “smart” cities and infrastructure.

Crain’s has a short piece on this today as does the PEP website.

Woo!

Speechifying

Lotta public speaking in the next few weeks. Most are local. If you’re interested in technology and urbanism come on out for a conversation.

University of Illinois Chicago College of Urban Planning Friday Forum

Friday, Feb. 24, 12p

“Data-Driven Chicago”

[detail]

University of Chicago Computation Institute Lecture

Monday, Feb. 27, 4:30p

“The City Is a Platform”

[detail]

City Club Public Policy Luncheon

Tuesday, March 6, 12p

[detail]

South by Southwest Interactive

Austin, TX

Monday, March 12, 12:30p

“The Future of Cities: Technology in Public Service”

[detail]

I’m particularly excited about that last one as I get to share a panel with Chris Vein, Nick Grossman, Abhi Nemani, Nigel Jacob, and Rachel Sterne. Perhaps the conversation will focus on just what the hell I am doing on the same stage as such accomplished folk. If you’ll be at SXSW, you should definitely drop by for this one.

On Leaving IBM

Today, May 12, is my last working day with IBM, my employer for the last 13 years. It’s tough to adequately express how many opportunities IBM has afforded me and how difficult it was to make the decision to depart.

What follows is my shot at the first. I’ll let you guess at the second. (Hint: If you’re looking for a juicy exposé or vindictive exit letter, this ain’t it.)

1998, Georgia Tech: I was finishing up a masters degree that didn’t exist three years prior. The tech bubble had not burst and everyone in the circles I moved in was decamping for the world of stock options, foosball tables, and the promise of becoming the next Netscape.

I had two offers on the table, one from a classic dotcom agency, and one fromIBM, a classic old person company. I struggled mightily with the decision and frankly I still don’t know exactly why I chose IBM. Might have been the I in the acronym — the suggestion of a career spent globetrotting and doing business in different cultures. But I do know that the other company ceased to exist only a few years later.

IBM then was a resurgent corporation back from the brink of death. Atlanta was the home to its Interactive Media organization, a kind of skunkworks dotcom agency — which I joined as a producer. (We had so few models internally for the web work we were doing that we borrowed titles from flim: producer, executive producer, even continuity director.) It was frenetic, design-oriented, and full of lots of people who very definitely were not old. (And neither was I. Dig the hair!)

I lucked into the part of Interactive Media that was building systems for live event coverage of the sports properties that IBM sponsored, primarily pro tennis, golf, and the Olympics. This was the world before cacheing and the cloud and so a certain amount of terror accompanied the task of running websites that could handle the load of sports fans worldwide checking scores covertly from work.

We were “webcasting,” crammed into windowless rooms or awful rented trailers, but let’s face it, I was onsite at Wimbledon, the US Open, and the Ryder Cup. And loving it. The stories and friendships from those days are some of the most cherished of my career. (Someday ask me about a sopping-wet Brooke Shields hiding out in our nerd bunker during a rain delay at Flushing Meadows.)

The moment that established the trajectory that would basically define my career at IBM — diving way deep, obsessively even, into the subject matter surrounding my projects — arrived with the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. I had been tagged by colleagues as “the guy who likes books” given my undergraduate pursuits, so I suppose it is not surprising that I would be given the lead on a cultural project. It was a massive undertaking, digitizing thousands of works of art, presenting it on a still-nascent web, and working across cultural and linguistic differences. It was, in short, a template for much of the work to follow.

With one interlude. In 2000 I somehow finagled my way onto the cruise shipIBM had rented as living quarters for its guests to the Sydney Olympics. A pal and I provided tech support in the computer lab for IBM customers to check e-mail and download digital photos. (It was the era before ubiquitous laptops and connectivity, you see.) It was also, perhaps, the greatest gig of all time.

Over the course of the next many years I had the privilege of leading a number of increasingly complex projects in cultural heritage. Eternal Egyptapplied the concept of an online museum to an entire country, across multiple institutions, and nearly all historical eras. Add in mobile phone and PDAaccess (hey, it was 2003!) and a History Channel documentary and you had the making of something great.

Moving away from material culture and into the realm of society and history, I was honored to lead the team that built the website for the newest Smithsonian museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, something not set to open on the mall for several years. TheNMAAHC Memory Book was one of the first citizen-curated content projects for the Smithsonian and is a great foundation for the museum’s bottom-up presentation of the African-American experience.

More directly in the lineage of the Hermitage and Eternal Egypt, The Forbidden City: Beyond Space and Time took IBM’s cultural heritage work away from the web and into multi-user 3D space. Modeling the square kilometer of the Ming-Qing era complex was my first taste of city design and crafting spatial interactions, a foreshadowing of relatively great import.

Interspersed among the cultural work were a few important projects that were both responses to world events. The Katrina disaster mobilized a crack team in IBM to develop Jobs4Recovery, a site that aggregated and geo-located employment opportunity in the states hit by the hurricane. This was particularly meaningful to me as my wife’s family was directly, sadly affectedby the disaster and its aftermath.

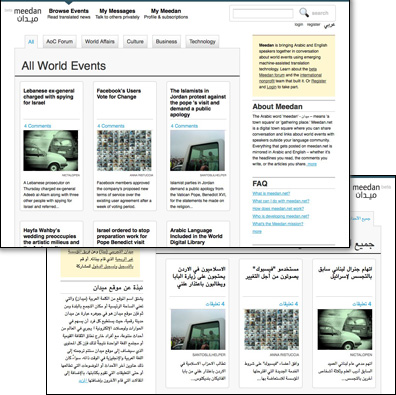

Working in Egypt before and after the 9/11 attacks gave me a perspective (and friendships) for which I am eternally grateful. So it was a real pleasure to work on Meedan, a news aggregrator/social network for current events in the Middle East and North Africa. Working with the non-profit of the same name, Meedan was built to use IBM machine translation and human volunteer editors and curators to provide English and Arabic translations of news stories and comments. I had worked much of my career presenting the treasures of the world’s material culture to broader audiences; Meedan was my opportunity to widen the definition of culture that we were hoping to bridge to others.

Perhaps the most transformative moment of my career came upon being accepted to the fledgling Corporate Service Corps, IBM’s internal “peace corps”, a hybrid leadership development and philanthropic program that sent small teams of IBM’ers to areas of the world that IBM does not currently do business. I joined the first team to West Africa and was thrilled to head to Kumasi, Ghana with nine other IBM’ers from around the world. We worked with small businesses to help them on all manner of problems. Being jolted out of a comfortable office setting to find common ground with colleagues from different lines of business and other countries was amazing enough, but I had the great fortune of our former nanny in Chicago, a native of Kumasi, returning to her family there and ensuring that I not only worked in Ghana but felt a part of the community there. It changed my life.

I got my first dose of what would become a full-on obsession in modeling complex systems for better decision-making when I inherited Rivers for Tomorrow from a retiring colleague. Rivers, a partnership with The Nature Conservancy, permits users to simulate different land use scenarios in river watersheds to see what the effects are downstream, so to speak, on water quality. It was a fun set of systems to model, but much hairier problems came shortly.

The project that I end on, whose roots I trace to the Forbidden City project, isCity Forward. I consider it a kind of simulator of cities using data in the same way that the Virtual Forbidden City was one in 3D graphics. You can read all about the project — heaven knows I have talked about it enough here and elsewhere, but the key thing is the world of urbanism that it opened to me. City Forward set me on a path to relationships with people making real change in cities around the world and showed me the promise of technology embedded in the everyday lives of city-dwellers. It is, in a word, the springboard that has launched me into my new role.

I realize that’s a pretty me-focused list of experiences and I will admit that this blog post is as much a personal retrospective as anything else. But I think it does a good job of making it clear how important IBM has been to my professional development, personal growth, and intellectual satisfaction. I could not have asked for a more fulfilling past 13 years and I leave with nothing but respect and thanks for what the company has done for my family and me.

And yet the list above glaringly lacks the most important thing that I am leaving. My colleagues in IBM have, to the person, been the most meaningful aspect of my career. To list everyone who made me a smarter person, a better colleague, a more understanding manager, a more collaborative partner, or better world citizen would take several blog posts, but suffice to say that I met some of my very best friends, a few mentors, and even a few professional idols in my time with IBM. My gratitude for my colleagues at IBM exceeds my capacity to express. Thank you.

So what now? I am off to the role of Chief Technology Officer for the City of Chicago under our new mayor, Rahm Emanuel. That’s a post for another time, but it’s fair to say now that it was an offer I could not pass up. I have been preaching smarter cities for a very long time; to let an opportunity go by to take real action in the city I love most would have filled me with regret. It is time to put my money where my mouth is.

IBM turns 100 years old this summer — a fairly amazing accomplishment for any company, let alone an IT company. I’m proud of what IBM has achieved, but even more proud of the people who have done the work. I’ll leave you with this extraordinary video, the best portrait of the people of IBM that I know. And the very essence of what I will miss most.

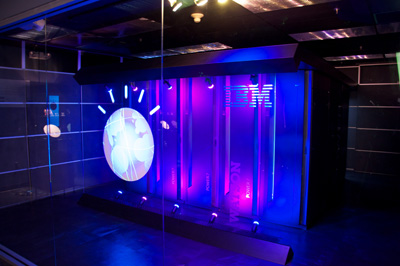

What it’s like to match wits with a supercomputer

I spent most of the May 1997 rematch between chess world champion Garry Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer sitting in a grad school classroom. I think it was Intro to Human-Computer Interaction, ironically enough. The professor projected a clunky Java-powered chess board “webcast” (the term was new, as was the web) so we could follow the match. The pace of chess being deliberative and glacial, it really wasn’t a distraction. Not to mention that, at the time, I didn’t know how to play chess. But I do remember people caring deeply about the outcome. I went to work for IBM the following year.

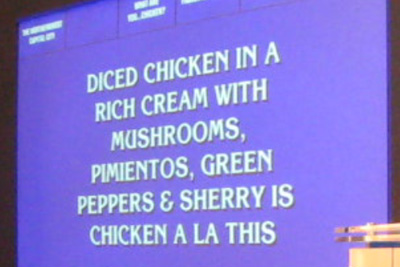

Deep Blue’s descendant, if not in code or microchips then in the style of its coming-out party, is Watson, a massively parallel assemblage of Power 7 processors and natural language-parsing algorithms. Watson, if you’re not a geek or a game show enthusiast, was the computer that played Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter on Jeopardy Feb. 14-16 of this year. Watson won.

Wednesday of last week I got a chance to play Watson on the Jeopardy set built at our research facility for the show. I did not win.

But I did hold the lead for a time and, in fact, I beat Watson during an unrecorded practice round. Honest!

Jeffrey Plaut of Global Strategy and I were the two human competitors selected to go up against Watson in a demonstration match. We did so at the culmination of a few hours of discussion with leaders from the humanitarian sector on how to expand Watson’s repertoire to put it to work in areas that matter. (More on that in a bit.)

IBM built a complete Jeopardy set for the actual televised match. Sony has lots of experience with this, as Jeopardy often goes on the road. But it’s clearly a hack: TV made the set look a lot bigger that it really is and the show’s producers had to jump through hoops to provide dressing room space and keep the contestants segregated from interacting with IBM’ers (to avoid claims of collusion, I suppose). Ken Jennings has some typically humorous insight on this.

Trebek was long gone, so we had the project manager for Watson host the session I competed in. He’s actually very good, as Watson went through a year of training with past winners and stand-in hosts. I was to play one round of Jeopardy. The rules were the same as the real game and Watson was at full computing capacity, with two exceptions. We were told that we could ring in and then appeal to the audience for help and, most importantly, Watson’s ring-in time was slowed down by a quarter second. The first I took as an insult — if I was going to compete against a computer I was going to do it myself — the second was a blessing.

Standing at the podium is certainly nerve-wracking. There’s a small screen and light pen for scrawling your name and then the buzzer. I stood in Jennings’ spot and it was striking to see how worn the paint was on the buzzer. From sweat? Who knows, but that thing looked like it had been squeezed to death. Contestants can see the clue board and the host, of course, but there’s also a blue bar of light underneath the clues which is triggered manually by a producer once the host finishes reading the last syllable of the clue. This is the most important moment, as ringing in before the blue bar appears locks you out temporarily. Watson had to wait a quarter second at this point and I am convinced it is the only reason we humans were able to get an answer in edgewise.

In a way, this moment is as much human-versus-human as anything. You’re trying to predict exactly when the producer will trigger the go light. Factor in some electrical delay for the plunger and it can be a real crapshoot. This is why past champions perfect their buzzer technique and ring in no matter what. They just assume they will know the answer and be able to retrieve it in the three seconds they are given.

I got a bit of a roll in the category called “Saints Be Praised”. My Catholic upbringing, study in Rome, and fascination with weird forms of martyrhood finally paid dividends. (I also learned after the match that my human competitor was Jewish and largely clueless about the category.) The video above shows me answering a question correctly — something that seems to have shocked my colleagues and the audience. (And I would have disgraced every facet of personal heritage had I messed up a question about an Italian Catholic from Chicago.)

This clue was more interesting as Watson and I both got it wrong. The category was “What are you … chicken?” about chicken-based foods. Maybe my brain was still in Italian mode as I incorrectly responded “Marsala”, but Watson’s answer — “What is sauce?” — was way wrong, categorically so. This is insightful. For one, the answer, “What is Chicken A La King,” if Watson had come across it at all, was likely confusing since “king” can have so many other contexts in natural language. But Watson was confident enough to ring in anyway and its answer was basically a description of what makes Chicken A La King different from regular chicken. Note that the word “sauce” does not exist in the clue. Watson was finishing the sentence.

What’s most important and too-infrequently mentioned is that Watson is not connected to the Internet. And even if it were, because of the puns, word play, and often contorted syntax of Jeopardy clues, Google wouldn’t be very useful anyway. Try searching on the clue above and you’ll get one hit — and that only because we were apparently playing a category that had already been played and logged online by Jeopardy fans. The actual match questions during the Jennings-Rutter match were brand new. The Internet is no lifeline for questions posed in natural language.

At one point I had less than zero (I blew a Daily Double) while Jeff got on a roll asking the audience for help. And the audience was nearly always right. Call it human parallel processing. But if I was going to go down in flames to a computer I was damn sure not going to lose to another bag of carbon and water. I did squeak out a victory with a small “v” — and Watson was even gracious about it.

Thinking back it is interesting to note that nearly all my correct answers were from things I had learned through experience, not book-ingested facts. I would not have known the components of Chicken Tetrazini did I not love to eat it. I would probably not know Mother Cabrini if I didn’t take the L past the Cabrini-Green housing project every day on the way to work. This is the biggest difference between human intelligence and Watson, it seems to me. Watson does learn and make connections between concepts — and this is clearly what makes it so unique — but it does not learn in an embodied way. That is, it does not experience anything. It has no capacity for a fact to be strongly imprinted on it because of physical sensation, or habit, or happenstance — all major factors in human act of learning.

In Watson’s most-discussed screw-up on the actual show, where it answered “Toronto” when given two clues about Chicago’s airports, there’s IBM’s very valid explanation (weak category indicator, cities in the US called Toronto, difficult phrasing), but it was also noted that Watson has never been stuck at O’Hare, as virtually every air traveler has. (The UK-born author of this piece has actually be stranded for so long that he wandered around the airport and learned that it was named for the WWII aviator Butch O’Hare.) Which isn’t to say that a computer could never achieve embodied knowledge, but that’s not where we are now.

But all of it was just icing on the cake. The audience was not there to see me make a fool of myself (though perhaps a few co-workers were). We were there to discuss the practical, socially-relevant applications of Watson’s natural-language processing in fields directly benefiting humanity.

Healthcare is a primary focus. It isn’t a huge leap to see a patient’s own description of what ails him or her as the (vague, weakly-indicating) clue in Jeopardy. Run the matching algorithm against the huge corpus of medical literature and you have a diagnostic aid. This is especially useful in that Watson could provide the physician its confidence level and the logical chain of “evidence” that it used to arrive at the possible diagnoses. Work to create a “Doctor” Watson is well underway.

As interesting to my colleagues and I are applications of Watson to social services, education, and city management. Imagine setting Watson to work on the huge database of past 311 service call requests. We could potentially move beyond interesting visualizations and correlations to more efficient ways to deploy resources. This isn’t about replacing call centers but about enabling them to view 311 requests — a kind of massive, hyperlocal index of what a city cares about — as an interconnected system of causes and effects. And that’s merely the application most interesting to me. There are dozens of areas to apply Watson, immediately.

The cover story of The Atlantic this month, Mind vs. Machine, is all about humanity’s half-century attempt to create a computer that would pass the Turing Test — which would, in other words, be able to pass itself off as a human, convincingly. (We’re not there yet, though we’ve come tantalizingly close.) Watson does not pass the Turing test, for all sorts of reasons, but the truth is that what we’ve learned from it — what I learned personally in a single round of Jeopardy — is that the closer we get to creating human-like intelligence in a machine, the more finely-nuanced our understanding of our own cognitive faculties becomes. The last mile to true AI will be the most difficult, primarily because we’re simultaneously trying to crack a technical problem and figure out what, in the end, makes human intelligence human.

Welcome to City Forward

“I felt the physical city to be a perfect equation for a great abstraction.”

Homage to Victory Boogie Woogie #1, Leon Smith

It’s hard not to see the reasoning behind that quote from the Mondrian-acolyte painter Leon Polk Smith when you learn that he grew up amidst the gridded fields of Oklahoma before moving to New York City.

But it’s instructive in another way. The physical city certainly is the expression of abstract things. The desires of its inhabitants, the collective aesthetic of cultures, the movement of goods, the education, safety, and utilities that strengthen or weaken it.

What’s been missing is a good way to describe that equation. And that’s why I’m pleased to have been a part of the development of City Forward. This site is a first step in aggregating, visualizing, and socializing the abstract vital signs of cities worldwide to permit a better understanding of the world we live in. It’s rich with functionality — honed over many months with amazing feedback from our beta community — to provide a single place to work with the data our cities are opening up.

We’re not alone in this endeavor and we hope to play a critical role in the ecosystem of applications that are making public data more useful, insightful, and actionable.

City Forward has a lot to offer. I encourage you to learn more about what it can do (perhaps watch the video) and to create your own explorations of the data within. Help us find the equations so we can describe a better future for our metropolitan regions.

My 15th minute

Photo by Josh Nard

So. Remember when I went to Africa last year? Life-changing, job-changing, everything-changing. Yes, well, the program I was a part of — called the IBM Corporate Service Corps — recently was profiled by Fortune Magazine in their issue on the best companies for leaders. The CSC is both a leadership development program and a way to assist small businesses in “pre-emerging” markets. And Fortune loves IBM for that (and other things).

The other news — which took me quite by surprise — is that my experience is actually the opening lede to the story (which in print is on the cover). Wow.

Have a read: How to build great leaders, Fortune Magazine, Nov. 20, 2009.

Meedan

So there’s this project I’ve been working on for years which I’ve been (mostly) mum about.

No more. Now’s the time for talking — across borders, between languages, outside of our disconnected ecosystems of news-gathering.

Welcome to Meedan.

Meedan is a space for conversation and networking — the word ‘meedan’ (ميدان) means ‘town square’ or ‘gathering place’ in Arabic — where everything posted is mirrored between English and Arabic using a mix of human and machine translation.

The project is based on the simple (even self-evident) premise: it’s easy to distrust and misconstrue someone you can’t have a one-on-one conversation with. While the web is a place of massive social interaction, this interaction is almost universally bounded within language groups — a startling barrier to true understanding.

Meedan focuses on reducing this barrier by enabling English and Arabic speakers to

- share news and opinion from the English-language and Arabic-language web

- join cross-language conversations about technology, arts, business and politics

- widen their social network with people who speak a different language and who partake of very different cultures

- write, vet and edit translations in collaboration with users around the world

The project is led by the Meedan organization, a non-profit in San Francisco, with technical development and translation technologies from IBM. Here’s a video introducing Meedan.

So, how does it work?

Comments are instantly translated into Arabic or English using IBM’s machine translation. But because machine translation is not perfect (especially with a language as complex as Arabic) community translators are allowed to edit the translation.

This ability to improve the translations works like editing a Wikipedia article and, in my opinion, is the really novel use of social media on Meedan. (The plan is to allow translations to be rated such that, over time, the best translators emerge as part of a social network of trusted bilingual users.) As a final step, professional translators vet the community-submitted edits. Here’s a video demonstrating comment translation.

These hybrid machine-human translations are then fed back into the system which learns from the ever-growing, vetted corpus. The more people talk, the smarter the machine translation becomes.

Can the system be gamed? Sure. Will there still be misunderstanding, enmity, and deliberate mischievousness? Likely. You can’t change human nature. What Meedan does is provide tools for mitigating the less salutary effects of long-distance, networked conversation between peoples of different cultures.

That’s the hope, anyway. Meedan is in an open (though relatively quiet) beta phase right now. Come on in.

Update: You can get updates via Meedan on Twitter or at their blog.

Everything I need to know about people management I learned from M

A while back I was editing my annual business goals, the benchmark against which I am evaluated at the end of the year. Coincidentally my wife and I and some friends were also watching the latest Bond flick, Quantum of Solace.

Turns out there is a ton of great management advice sprinkled in between the car chases, gun fights, and general tuxedo-style bad-assery. Nearly all of these are said by Judi Dench’s icy Q M*.

How to tell someone that they may be laid off

“I need to know that I can trust you.”

How to give someone the appearance of a last chance even though in your mind you’ve already laid them off

“I need to know you’re on the team. I need to know you value your career.”

How to answer a phone with confidence

“What is it?”

How to delegate

When asked for something have an assistant say on your behalf “Not in the mood.”

How to motivate

“Impress me.”

How to deal with competitors

Ask “Is he one of ours?” If he is not, say “Then he shouldn’t be looking at me.”

How to compliment a colleague

“There is something horribly efficient about you.”

How to deal with government “regulation”

“I don’t give a shit about the CIA.”

How to deal with an over-eager assistant

“[I need] nothing, go away.”

How to end a conversation

Calmly interject “Quiet,” then walk away.

* Update: Wasn’t minding my P’s and Q’s and got M’s code name wrong in the original of this post. Sorry, Bond nerds!

Supercharged culture-geeking

This past Monday, IBM and the Office of Digital Humanities of the NEH convened a bunch of smart folks to talk about what humanities scholars would do with access to a supercomputer, real or distributed. I had been looking forward to this discussion for months, if not years in the abstract. It was a wonderful convergence of two of my life interests.

We had a broad representation of disciplines — a librarian, a historian, a few English profs, an Afro-American studies professor, some freakishly accomplished computer scientists, and a bunch of “general unclassifiable” folks who perfectly straddle the worlds of technology and culture.

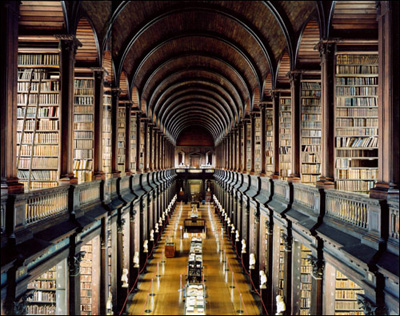

The Library of Trinity College, Dublin

The grid has about a million devices on it and packs some serious processing power, but to date the only projects that have run on it have been in the life sciences. We were trying to think beyond that yesterday.

My job was to pose some questions to help form problems — mostly because, outside the sciences, researchers just don’t think in terms of issues that need high performance computing. But that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. It’s funny how our tools limit how we even conceptualize problems.

On the other hand you might argue that this is a hammer in search of a nail. OK, fine. But have you seen this hammer?

Here’s some of what I asked:

- Are there long-standing problems or disputes in the humanities that are unresolved because of an inability to adequately analyze (rather than interpret)?

- Where are the massive data sets in the humanities? Are they digital?

- Can we think of arts and culture more broadly than typical: across millennia, language, or discipline?

- Is large-scale simulation valuable to humanistic disciplines?

- What are some disciplinary intersections that have not been explored for lack of suitable starting points of commonality?

- Where is pattern-discovery most valuable?

- How do we formulate large problems with non-textual media?

I also offered some pie-in-the-sky ideas to jumpstart discussion, all completely personal fantasy projects. What if we …

- Perform an analysis of the entire English literary canon looking for rivers of influence and pools of plagiarism. (Literary forensics on steroids.)

- Map global linguistic “mutation” and migration to our knowledge of genetic variation and dispersal. (That’s right, get all language geek on the Genographic project!)

- Analyze all French paintings ever made for commonalities of approach, color, subject, object sizes.

- Map all the paintings in a given collection (or country) to their real world inspirations (Giverny, etc.) and provided ways to slice that up over time.

- Analyze imagery from of satellite photos of the jungles of southeast Asia to try to discover ancient structures covered by overgrowth.

- Determine the exact order of Plato’s dialogues by analyzing all the translations and “originals” for patterns of language use.

(Due credit for the last four of these go to Don Turnbull, a moonlighting humanist and fully-accredited nerd.)

Discussion swirled around but landed on two major topics both having to do with the relative unavailability of ready-to-process data in the humanities (compared to that in the sciences). Some noted that their own data sets were, at maximum, a few dozen gigabytes. Not exactly something you need a supercomputer for. The question I posed — where is the data? — was always in service of another goal, doing something with it.

But we soon realized that we were getting ahead of ourselves. Perhaps the very problem that massive processing power could solve was getting the data into a usable form in the first place.

The Great Library of the Jedi, Coruscant

At present it seems to me — I don’t speak for IBM here — that the biggest single problem we can solve with the grid in the humanities isn’t discipline-specific (yet), but is in taking digital-but-unstructured data and making it useful. OCR is one way, musical notation recognition and semantic tagging of visual art are others — basically any form of un-described data that can be given structure through analysis is promising. If the scope were large enough this would be a stunning contribution to scholars and ultimately to humanitiy.

The possibilities make me giddy. Supercomputer-grade OCR married to 400,000 volunteer humans (the owners/users of the million devices hooked to the grid) who might be enjoined to correct OCR errors, reCAPTCHA-style. Wetware meets hardware, falls in love, discuses poetry.

The other topic generating much discussion was grid-as-a-service. That is, using the grid not for a single project but for a bunch of smaller, humanities-related projects, divorcing the code that runs a project from the content that a scholar could load into it. You’d still need some sort of vetting process for the data that got loaded onto people’s machines, but individual scholars would not have to worry about whether their project was supercomputer-caliber or what program they would need to run. In a word, a service.

Who knows if either of these will happen. It’s time now to noodle on things. As always, if you have ideas for how you might use a humanitarian grid to solve a problem in arts or culture, drop a line. We’re open to anything at this point.

A few months ago Wired proclaimed The End of Theory, basically noting that more and more science is not being done in the classical hypothesize-model-test mode. This they claim is because we now have access to such large data sets and such powerful tools for recognizing patterns that there’s no need to form models beforehand.

This has not happened in arts and culture (and you can argue that Wired overstated the magnitude of the shift even in the sciences). But I have to believe that access to high performance computing will change the way insight is derived in the study of the humanities.

Slave to the cliché

Recently I’ve had occasion to reflect on the awful state of presentations. You see them all the time — in meetings, at conferences, shunted around via e-mail — and they sap the soul.

There are many aspects of crappy presentations, but I’ll focus here on only one.

From Wikipedia:

“Shave and a Haircut” featured in many early cartoons, played on things varying from car horns to window shutters banging in the wind. Decades later, the couplet became a plot device in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, the idea being that Toons cannot resist obeying cartoon conventions. Judge Doom uses this to lure Roger Rabbit out of hiding at the Terminal Bar by circling the room and tapping out the five beats on the walls.

Here’s the scene from the film:

In film there’s a term called “mickey mousing” which refers mostly derogatorily to the underscoring technique of using music to exactly ape what’s seen on screen. Early cinema used it all the time, as the medium was new and unexplored. Examples include playing a sea shanty when a ship floats into view or mimicking the slicing of Janet Leigh in the shower in Psycho.

As with any technique used smartly it had its place, but mickey mousing quickly devolved into caricature as a stock device in cartoons (hence the name). Music in cartoons, usually orchestral, almost always reinforces in the most literal way the action on screen. Which is fine, because cartoons are meant to be laughed at.

But most presentations are not meant to be laughed at — at least not all the way through — and this is a problem. The idea behind mickey mousing pervades most presentations. That is, presenters often attempt to reinforce what is being conveyed in one medium (usually bland bulleted text) with another (usually hideous clip art of illustration).

This is almost always a bad idea. And the reasons are many.

First, it distracts from the real message. Presentations should be about the presenter, not about what’s on screen. If there is an image on screen it should complement, even slightly modify what the speaker is saying, not mindlessly illustrate what the bullets say. (Which goes the same for the bullets too: if what you’re saying is on the screen why even present at all?)

Second, mickey mousing in presentations demeans the intelligence of your audience. Do you really need to put a clip art image of an airplane next to your point about airborne supply chain routes? Does this make your point more compelling? Might it not say something more about the point itself? Or your confidence in the point? Or maybe just your confidence as a presenter? Most audiences, if not snoozing, are smart enough to ask these questions themselves.

And sometimes bad graphics have much direr consequences.

There are plenty of resources out there to help you make a better presentation. If you want an example of an extraordinary interplay between what’s being said and what’s being shown, have a look at Dick Hardt’s Identity 2.0 talk from OSCON 2005.

My colleague Ian Smith has put together a great overview of strategies for making yours more persuasive and entertaining. Highly recommended.

Maybe the simplest piece of advice is to ask yourself, is my presentation a deliverable or a performance? That is, is it meant to be read, studied, and digested (a solitary activity) or is it meant to sketch broad themes to many people and connect the authority of the presenter with the validity of the material?

These two things — a document and a presentation — should almost never be the same thing. They can cover the same material, but throwing a presentation made for reading up on the screen is like projecting the score of a symphony in the orchestra hall in lieu of music.