Wood

Part one of the Ghanaian Handicraft series.

Wood-carving is one of the oldest craft traditions in Ghana. Wooden sculpture is produced throughout the country and has a high export value. Two weeks ago we visited the village of Ahwiaa to observe and talk to artisans trained in the traditional discipline.

Wood is delivered to them from the forests hewn roughly into the intended shape of the end product. From there small outdoor workshops of carvers set about shaping the objects into final form. The workshops are a welter of flying wood chips, sweat, and clanking. Masters silently instruct their apprentices.

It all seems so random and haphazard, but obviously these gentlemen know what they are doing. And they are all gentlemen. Female woodworking is taboo mostly because of the posture assumed by artisans: the wood chunk is held between the legs and shaped there. Ghanaians disapprove of tools being used in the vicinity of female genitals.

The artisans are preternaturally fit. They look carved from solid material too. The main implement is a metal gouge placed carefully on the wood and then struck by a mallet. The carvers wear two pairs of pants over one another for protection. The outer pants are ripped and frayed from numerous skewed strikes.

We visited the main woodworking area in Ghana, an area of the Ashanti region near Kumasi. Traditionally the king of the Ashanti (called the Asantahene, currently Otumfuo Nana Osei Tutu II) is the custodian of all arts in the region because of the historic relationship between craftsmanship and the royal house. What this means today is that he serves a quasi-governmental position of promotion and support for the arts, including being the nominal patron of our organization Aid to Artisans.

Aid to Artisans does more than just serve as a middleman for the producers. They hold courses on reforestation and forest management for their producers and recently purchased a small section of woodland as a kind of nursery/laboratory for the study of sustainability techniques.

And yet, it seems to be a losing battle. Every day I’ve seen huge trucks hauling massive felled trees. In fact they aren’t really trucks, just two sets of wheels lashed to the mammoth trunks. Even in Kakum, which is protected by law, there is logging taking place. One wonders how much longer this art form can survive without importing lumber.

More wood-carving video here.

Social bookmarking in Africa

Geeks in the West are infatuated with social media. And for good reason, sharing makes good, selfish sense. It allows processing the infoglut through the filter of people you know and trust. And yet, as in so many things that computers make easy, social sharing of data requires nothing more than a communication medium and a community.

Two weeks ago we visited Mfensi, a village outside of Kumasi graced with a clay-banked river. It is, thus, a pottery-making center. I’ll post about the fascinating process from river-bottom to pottery in a bit, but for now have a look at this. It isn’t graffiti, but rather the village phone book.

The mobile phone is king in Africa, of course, but there are no add-on services as in the West. No voicemail, no server-side contact list. You can call and text and that’s about it. So why not have a community address book? Scrawl it on the wall. No downtime — and if you need context you just ask someone. Simple and wonderfully efficient.

What I’m doing in Africa

I think some of you are wondering what I’m doing here in Africa besides site-seeing and longing for faster connectivity. It’s an odd thing, for sure.

There’s only one flight from the US to Accra, Ghana and I was on it. Looking around the cabin you see mostly Ghanaians and the white people you just wonder about. At the risk of grossly generalizing, I’d say business class is full of well-heeled business people and perhaps aid workers with enough frequent flyer miles to qualify. It’s a distinction I’ve been pondering since I arrived. Which am I?

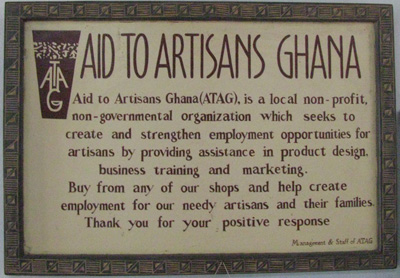

The IBM Corporate Service Corps, of which I am a part, is a bit of both. Our goals are equal measures corporate social responsibility for a global enterprise and advance market research in a promising country. There are 10 of us here — and teams elsewhere around the world — who are helping small businesses pro bono both because it is the right thing to do and because it provides us with knowledge about how best IBM could become part of the marketplace here.

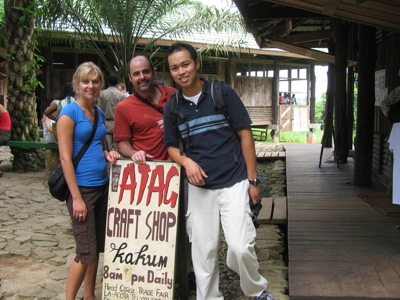

Each team has multiple projects. Mine is with a group called Aid to Artisans, the primary NGO tasked with promoting, educating, and marketing traditional Ghanaian handicraft locally and worldwide.

Here are our specific objectives.

- Assist ATAG to construct an interactive website to serve as an informational tool, showcasing the activities and operations of the organization to the outside world. The site should help the organisation to create more avenues for market development through e-commerce and to enable ATAG to communicate and link-up with members of its affiliate association (ACNAG) in a more free and convenient manner.

- Conduct a supply chain analysis serving to bridge the gap between the concept stage of product development to the production stage through to the end user of the product in question. The analysis will include sourcing raw materials, designing, prototyping, production of products to packaging, warehousing, exporting and retailing through to the consumer.

- Capture the relationship between the processes and document them, if possible, audio-visually.

It’s a strange middle ground we occupy. Not exactly business, not exactly aid. (Indeed, some NGO folks we’ve met expressed outright skepticism at our mission here. While, back home, most businesspeople take a while to understand why we’d ever go to Ghana.)

My sub-team colleagues are the talented Julie Lockwood and Charlie Ung.

When we’re not traveling to meet the producers in the villages or the exporters at the coast we work at the Aid to Artisans field office in Kumasi. It’s a great space at the Cultural Center. Can’t beat the ambient music.

In the queue is a series of posts on each of the different types of artisans we’ve visited. That’s the good stuff. Soon.

The integral trees

I’ve heard Ghana called “Africa for Beginners” mainly because it is relatively stable, economically promising, and English-speaking. Yet it is also not the Africa of Western, romantic stereotype. There’s no Heart of Darkness-esque jungle, no Lion King savanna. Ghana once was mostly rainforest, but logging and farmland creation mostly denuded the landscape in the last century.

Still there are patches, now protected. One of the best is Kakum National Park, just outside of Cape Coast a few dozen clicks from the beach. We visited Kakum on Saturday. It was breathtaking. Sublime in the true sense of the word: beautiful and terrifying.

Apart from the wildlife — which includes such rarities as pygmy forest elephants (I had no idea such a thing existed) and a crazy diversity of birds — the park’s main attraction is an elevated rope bridge walkway right through the tree canopy. It’s an amazing thing. You set out on it just a few meters above the ground and are several hundred feet above the forest floor before you realize you can’t turn back.

It’s all rope and wood plank and with the exception of the rusting steel wire brings immediately to mind the scene from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom where our hero hacks the bridge in two.

There are seven bridges in all, stretching more than 1000 feet between gigantic trees on which small viewing/rest platforms have been constructed.

It was all built in 1995 by shooting rope via crossbow from tree to tree, then scaling the monsters old school, ground-up style and rigging the rest. You don’t question the engineering as much as the 13 years of maintenance. Things deteriorate quickly in a rainforest. Also, big as the trees are, once you land on the platforms there’s a noticeable sway — emphatically not the thing you want to feel having just crossed the chasm. It’s scarier than it seems.

There isn’t a whole lot of wildlife-viewing up on the bridges. Mostly you’re battling the sweat that threatens to compromise your grip on the rope “rails” and hoping no one on your stretch panics.

An economy of enslavement

Last year I had the privilege of building the initial website for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the newest Smithsonian institution on the Mall in DC. It was a period of deep immersion for me in facets of my national history that I had only a survey-level understanding of. I was very much looking forward to visiting the slave castles of Ghana’s coast.

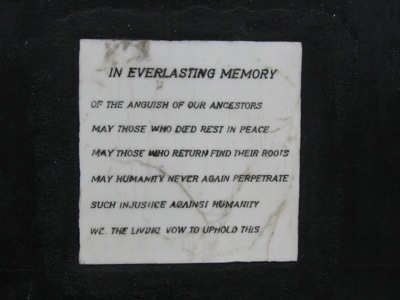

This past weekend we visited Elmina and Cape Coast, the largest transfer points for the Middle Passage of slaves to the Americas by European traders. Both towns feature beautiful white-washed castles that sit atop dungeons of horrific ambience and memory. They held about 2,000 male and female slaves at a time before transfer through “doors of no return” to awaiting ships.

I’ve been in Africa for over two weeks and not once felt self-conscious about my skin color. But inside these castles I couldn’t help but feel like an interloper. No one made me feel this way, to be sure. And I felt no personal guilt: my family came to the US well after the slave trade was abolished. And yet, touring the castle with two African-American couples felt slightly strange, like I was intruding on something sacred. The slave dungeons were full of flowers left by descendants.

At dinner that night I told Asha that slavery is a source of shame for America (though, I suppose, in truth I was speaking for myself). She added that it is a source of shame for Ghana too. The peoples of Ghana are as implicated in the trade as Europeans of course. White traders didn’t raid the interior of Africa for slaves; captives were traded from rival tribes for weapons, gunpowder, and alcohol. Of all the parties involved in this foul enterprise, only the slaves escape blame.

You pass through the Door of No Return in Cape Coast Castle and you’re back in the present. Fishermen mend nets in the shadow of the fort, carrying on the work that existed before the Europeans came. Children look out to sea and frolic in the waves. The past is just a big white building.

Off the map

Get in a cab in Chicago and chances are better than not that your driver is from West Africa — often Ghanaian, usually Nigerian. In my experience they know the city as well as other drivers, if not slightly better — certainly better than I do.

And this is why I am utterly perplexed at what I now understand as bald fact: Ghanaians in Ghana are terrible at estimating distance. Ask three Ghanaians how far from points A to B and you will get wildly different estimates. Five minutes from one person versus thirty minutes from another is not unheard of. But even when you ask for distances in units of length you will get absurd variance, or no earthly idea at all. Far versus not far. And not far usually ends up being at least 30 km.

This person says Kumasi to Accra is 2 hours; that person says 6 hours. One of these people is wrong.

I heard a Ghanaian refer to GMT as “Ghana Man Time”. Cracked me up. (By the way, I was bisected by the real GMT yesterday.)

It isn’t just distance and time. Today I headed out on my own to arrange a dinner with some students from Michigan Tech working in Accra. I grabbed a map of Accra that had on it the restaurant I wanted to go to. I approached a cabbie who looked at the map. He flagged another driver, then another, then another, until I had a small crowd gathered looking at my guide book. Much excited chattering in Ga (different language here in Accra; my Twi was useless — or, rather, more useless than normal).

Finally it dawned on me. As politely as I could I asked “You don’t know how to read a map, do you?” They immediately all confirmed that the map itself meant nothing to them, though they easily read the labels and words. They were obviously not illiterate. Just cartographically illiterate.

Now, I understand that it is sometimes hard to abstract one’s street-level knowledge of a city to an aerial version of the same. It is a puzzle to be solved, a kind of cognitive transform that involves whittling 3D to 2D. But someone whose job it is to actually know the city you’d think would have this ability.

Perhaps one aspect of the Ghanaian inability to judge distance/read maps/know the location of anything is that streets are very rarely signposted and, if marked, not really known by name. See, even though the drivers could read the street names on my map they had never heard of any of them. It’s all so very bizarre.

Here is a typical cab experience:

“Can you take me to Tante Maria restaurant?”

“Sure!”

“Do you know where that is?”

“Yes.”

[drive along aimlessly for 20 minutes]

“Do you know where we are going?”

“Yes.”

[drive along for 20 more minutes, generally back the way ye came]

“Are you sure you know where we are going?”

“Yes.”

[Taxi stops. Driver gets out and randomly polls people on the street for directions. Gets back in. Drives for 20 more minutes.]

This last sequence — the stop-and-inquire — typically happens at least three times per journey. Usually the outcome is that the cabbie ends up not only not knowing where he is going but usually not even where he is. It is at this point that you cut your losses and bail out.

Clearly this lack of spatial awareness is not something biological. Ghanaians in the US do just fine. So it must be cultural, something about Ghana itself that causes spacetime to warp. Like the island in Lost.

10 days in Ghana

I’m in Accra, Ghana now, back where this adventure started last week. It’s been wonderful and exciting, exhausting and not a little frightening. Let me provide an example that covers a single twenty-four hour period last week.

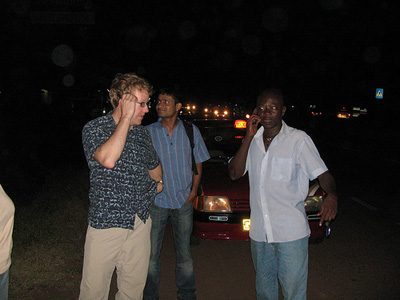

We have a “handler” named Asha. She works for Citizens Development Corps, which is based out of Accra, so she’s our only daily contact in Kumasi. Asha’s great: 23, urbane, well-educated, and a serious party girl. (I’ve nicknamed her “Brimful”, a reference she both likes and gets.) We talk music.

Asha has a friend who owns a club in Kumasi. I believe I found that fact out approximately 100 seconds before she had him on the phone and had procured an invitation for me to DJ there. So, last Thursday, not even a week in Ghana, I hauled my laptop over to Time Out for a truly impromptu set. (OK, it wasn’t the least prepared I have ever been, but it was close.)

Apart from having no Nigerian music on hand — whoops — and some uppity patrons miffed that karaoke night was being upstaged by an obruni (Twi: “whitey”), it was pure joy.

I started with standard (even clichéd) Western tunes, quickly sprinted to more contemporary beats, veered over to Adam Beyer and Talvin Singh, did my best not to maul a bunch of Ghanaian High Life music I have, then ended with a long set of trance to placate the Tiësto-craving Lebanese who were crawling all over the plexiglass in front of the booth.

In short it was an amazing high. The club owner woke me up with a phone call at 7 the next morning to ask me if I would do it again. Quite a compliment, despite the hangover from the free (hooch) gin he paid me in.

And now a photo interlude. I just love the gazes of these kids.

The next day was a bit different. We were criss-crossing Kumasi on our way out of town to visit villages where traditional handicrafts are created. Talking to artisans and observing their trade in action was the first part of our task here (much more on which in a future post). It was thrilling.

As we were heading back into town for lunch our two Ghanaian colleagues in the front seat gasped and slowed the card down. Now, readers who have been to Ghana will know that no Ghanaian motorist ever gasps, blinks, slows down or really even cares. It is a massive deathrace free-for-all on the streets — a fact made laughable by the cheery Christian slogans painted on the back of nearly every car.

But gasp they did. Lying in the median of the street on the left side of our car, right outside my rolled-down window, was the dismembered corpse of a human being. It was a man. At first I thought it was a car crash victim, but as I looked closer I realized that he had been hacked with a long blade. It was perfectly obvious and completely nauseating, reminding me instantly of the way a roadside vendor had opened up a coconut for us the day before. The dead man’s head was flayed open from numerous machete blows.

But there was no blood on the street. This person had been murdered elsewhere, mutilated, and put out on show. A lynching. We pulled away and for several minutes the whole car was silent. I was shaking. Finally we tried to ask our hosts what in the hell we had just seen. They were upset too, though it was hard to tell exactly why.

They explained that crime was on the rise in the Ashanti region and that people were becoming increasingly unhappy with the sentences delivered by the court system. As such, vigilante murders were becoming more and more common as angry mobs sought to punish and deter crime. Obviously our hosts had no idea what crime this guy had committed — if he had done so at all — but that was their answer: vigilantism.

Fair to say that little episode annihilated any high I was riding from DJing the night before. I couldn’t shake the image, wished I hadn’t stared. We did little work the rest of the day that required lots of talking. No one really wanted to interact. That night none of us could sleep.

I suppose there’s an upside to being shaken so deeply. I’m much more sober about Ghana now. It’s still a wonderful and special place, but I think I can evaluate it more objectively now. The senseless horror of that corpse in the street (with children playing around!) pretty firmly knocked off the rose-colored glasses I had on.

In between these two poles of emotion are ten days of fantastic new experiences. I’ve uploaded all the photos to date and as much video as this poor bandwidth can handle. Here’s the full set, updated nearly daily.

Bear with me as I’ve not properly tagged or annotated most images yet (and some of them really require explanation). Also, most photos have no high-res version. Just too bandwidth-scarce over here. Will replace them when I am back home.

Stay tuned for a multi-part series on the visiting the artisan villages and documenting their work. Amazing stuff comin’.

Thanks for reading!

How to save America

With John 7,000 miles away in a third world country, I have decided to fill in for him. Now, taking his wife out for a night on the town could be a little awkward and very inconvenient for me. Instead, I have decided to guest blog on this widely revered Ascent Stage.

My name is Cory Ritterbusch, and I am the only ecologist that John knows. Some of you AS die-hards may remember my blog PrairieWorks being cited in the past. I practice a small but growing form of land conservation known as Restoration Ecology in the rural Midwest. Ecological Restoration, as a verb, is the practice of repairing a damaged or destroyed ecosystem. Let’s try to get our arms around the man-child that is ecological restoration to show you: How you can utilize it in some of your decision making, how to view the landscape in a new way, the power that humans possess and the damage we can reverse.

For millions of years American Indians and the ecosystem co-existed together here in America rather nicely. What is now corn and soybean fields were extensive prairies, savannas and woodlands harboring thousands of different species. Intermingled amongst these prairies were forests, wetlands, bogs, fens, and so on. There was a very smooth and seamless transition into one another without fragmentation. These ecosystems were on fire frequently, started by lighting strikes and by intentional means by Indians. It was a part of the natural process here in America for millions of years. With fire, the Midwest remained open without many trees. The plants living here adapted to these fires and became dependent on them for survival.

Beginning in the early 1800s pioneers began entering these wild areas and by 1850 the landscape had become extremely altered. Prairies were plowed into crop fields, woodlands were cut for timber and wetlands were drained. This had a detrimental effect on the species that had existed here for millions of years. With the suppression of fire and the introduction of plants from other continents, the conservative native plants had a hard time competing and were eventually extirpated. Luckily, small areas known as remnants were spared and botanists could study these areas to learn about them. These are now a benchmark for comparison and a seed bank for plant propagation. Today, restoration ecologists are mimicking the natural processes in hopes of recreating the glory of the prairie’s former past.

The landscape, agricultural and energy industries have also taken notice and are learning from these ghost plants of the past. We are now utilizing native plants to amend troublesome site conditions and are designing landscapes that provide a greater sense of place. The deep root systems that native plants formed after millions of years of harsh weather conditions are being utilized for many applications including: Controlling erosion, removing toxins from soils, creating landscapes that do not require water and fertilizers, planting flower filled areas in sub-par soil conditions and for producing ethanol. Native plants also offer a greater sense of place rather than utilizing the same set of plants from state to state and region to region, regardless of climate and soil types. For example, an Applebee’s restaurant chain will use the same building design and landscape design for all of its locations in today’s current streamlined thought process.

Much like Frank Lloyd Wright’s house designs incorporated elements of local materials, we are now doing this outdoors. Ironically, for the first time we are beginning to create landscapes that are of American influence rather than English and Japanese, the norm for the last two centuries. Replacing lawns, which have large maintenance requirements, with short grasses native to the western Midwest is just one example of how we can utilize native flora to reduce financial and natural resource strains for the betterment of humanity. Soon, we hope that the 55 billion dollar landscape industry can be trained in local plants rather than the sharpening of blades at the cost of a depleting water supply.

History comes full circle sometimes. The plants that we destroyed to create food to feed a nation can now be utilized to solve many important issues here at home. Utilizing perennial prairie plants for ethanol, installing plants that reduce labor inputs, attracting wildlife, reminding us where we are, cleaning our air and water, all while stabilizing soil in the process can be useful tools as we look towards the future. The plants that were once used to sustain an entire population of native people may do so again.

Thanks to John for allowing me to preach the power of native plants.

Cory Ritterbusch

Ghana intermittent

I’m in Kumasi on an Internet connection frailer than a house of cards. But hey, better than nothing. Here’s the quick and dirty. We’re settled into Kumasi, our guest house, and our places of work. I’m stationed with two teammates at the Ghana Cultural Center, which houses my partner Aid to Artisans. Looks like an achievable list of tasks for four weeks and the workspace is as good as it gets. No air conditioning, but I did get to shake it with traditional Ashanti dancers during a break today. Can’t beat that.

Yes, there’s video of that, as well as some truly great photos — but the hard truth is that the connection in Kumasi is crap. (I’ve tested three places now.) Download is tolerable; upload horrendous. Can’t even get a single photo up. So, media may have to wait until I can get back to Accra. Shame. But on the other hand I guess I’ll just have to be more descriptive in my posts.

Tomorrow it is off to a few villages outside of Kumasi to meet the makers of three types of traditional arts: brass-, wood-, and textile-based. They are the beginning of the road in the supply chain and the beginning of our analysis, plus seeing them at work will be a great treat. Can’t wait.

So, expect a longish dispatch in the next few days. And sorry for the quick spurt of media then nothing. WAWA: West Africa wins again. (It has a bit of a streak going.)

Update: obviously I have added media where possible.

A little bit about Ghana

The more you know …

Ghana, formerly known as the Gold Coast, was the first nation in Africa to receive independence from colonial rule in 1957.

Accra, Ghana, capital of the country, is a sister city of Chicago, USA.

There is no place on Earth you can travel to and require more vaccinations than coastal West Africa.

Ghana is the size of the US state of Oregon (roughly 92,000 miles2).

The name Ghana refers to the ancient empire of Ghana located in Senegal, Mauritania, and Mali with no overlap whatsoever to the current geographical boundaries of the country.

Ghana is the country closest to the center of the globe, as defined by international measurement. The prime meridian runs through it and the equator is only a few degrees south of the coast.

An amazing amount of the world’s scrap electronics end up in Ghana for precious metal recycling.

This is the Cicero Guest House, where I will be staying. It ain’t the Four Seasons, but I’m not complaining.

So that’s it for posts pre-departure — maybe until Aug. 15 given connectivity, but I doubt it. I’ll be chronicling the adventure here (much as I did in Italy exactly one year ago) and on the newly-launched official IBM Corporate Service Corps blog.

Thanks to everyone for the well wishes, offers to assist with the family while I am gone, and claims on my personal items should I not return.