Cena Lucana

May 20 was the Day of the Lucani, a completely made-up, sparsely-documented celebration for people whose ancestors can be traced to the lonely region of Basilicata, Italy. This roughly triangular province, called Lucania by ancient Greeks, is the instep of the boot of Italy, a mountainous, relatively arid landscape sandwiched between the Tyrrhenian and Ionian Seas that Norman Douglas called “the Sahara of Italy” in 1915. My great-grandparents came to America from this region in 1903 — as did very many of their compatriots. So much so that in the early part of the 20th century the volume of émigrés exceeded the birthrate.

I’ve visited Basilicata three times (and written a lot about it), meeting people along the way each time. A few weeks ago my friend Daniele Bracuto, a designer from my great-grandparents’ village of Barile, posted a menu exclusively comprised of specialities from that small town.

This is remarkable for a few reasons. First, though many (most?) Italian-Americans can trace their roots to Southern Italy, there is a dearth of cookbooks from there. (Sicily is an exception.) One might attribute this to America’s continued fascination with all things Tuscan, but the truth is that even today there is a real ignorance of Italian culture south of Rome. Christ stopped at Eboli and apparently so did the cookbook authors.

The other reason this is exceptional is that Barile is a tiny place, known really only for three things: 1) an extraordinary wine called Aglianico del Vulture; 2) its position on the slope of a majestic, extinct volcano; and 3) that its citizens lived in caves carved from limestone into the 20th century. Food, you will note, does not distinguish Barile (or, really, Basilicata — there is a reason many Southern Italian dishes use hot peppers). But I was wrong about that and I had a menu to prove it.

Daniele sent me the chefs’ recipes. They were in Italian (of course), some Arbëreshë (I think), and scaled to serve many dozens of people. There was no way I was not going to make it, terrible translation and portioning be damned.

Now, I have been practicing cooking as ancestor worship for a long time (here’s Spaghetti All’assassino, scorched wheat pasta, and Carbone Dolce). But this was a challenge above and beyond. I headed to Eataly in Chicago for expert help. For one, I was looking for tagliatelle mollicate, a kind of thick, serrated linguini I had never heard of. But Antonio, the legit paisan pasta monger at Eataly, knew of it and called it “reginelle” pasta. But Eataly did not carry it, so … he made it, by hand, with a zig-zag cutting tool!

Suffice to say there was a lot of improvisation. I chose two of the four courses from Daniele’s menu. The pasta dish and a cod and bean puree dish. Recipes are included below in Italian lest you make fun of my translation. Original proportions. Run it through Google Translate if you want a real laugh.

Tumact Me Tulez

(Tagliatelle mollicate con sugo alle noci ed alici)10 kg di reginelle

5 kg di mollica di pane

2 vasetti da 500 grammi di alici

16 kg di pelati

2 kg di noci puliteProcedimento:

Preparare il sughetto con olio aglio e separatamente tagliare le alicette a pezzettini ed immergerle nel soffritto. Aggiungere il pomodoro e portare a cottura. A parte in una padella fare tostare i gherighi di noce con la mollica di pane e un po’ di olio fino a farlo diventare croccante. A fine cottura aggiungere una spolverata di prezzemolo. Cuocere la pasta e saltare in una parte del sughetto aggiungendo un po’ di mollica aromatizzata. Impiattare aggiungendo uno o due cucchiai di sugo ed abbondante mollica di pane.

Duo di baccalà su passatina di fagioli di sarconi e peperoni cruschi di Senise

Baccalà 20 kg ammollato

7 kg di fagioli

1,5 kg di peperoni cruschi

2 kg di patate a pasta gialla

250gr di lardo

100 cialde di pane

Timo, Rosmarino, cipolla, prezzemolo, Alloro, peperoncino, aglio.Procedimento:

Baccalà: Spellare il baccalà, togliere la pelle e tagliandola a triangolini farla cuocere in forno con un filo di olio fino a farla diventare croccante per guarnizione. Tagliare il baccalà e creare 100 pezzi di 4cmx4cm circa l’uno, cucinare sottovuoto al 50% unendo timo, poco olio e pepe, cucinando a vapore a 80° (forno a temperatura controllata) se non ha il forno con buste per cottura in acqua quasi al bollore. A parte utilizzando la parte rimanente del baccalà (NB utilizzare le parti più alte del baccalà per i 100 pezzi e le parti più basse verso la coda per la pallina di baccalà), cuocere a vapore controllato sempre con timo olio e pepe e a fine cottura frullarlo insieme alle patate lesse e servire le palline con una pinza pallina gelato.Fagioli: Mettere a bagno i fagioli la sera prima, successivamente scolarli e cucinarli in acqua con poco sale e qualche foglia di alloro. A parte fare un fondo con cipolla tritata, poco peperoncino, un rametto di rosmarino e del lardo. Levare il rosmarino ed unire i fagioli cotti precedentemente. Lasciare insaporire ed aggiustare di sale e pepe. Utilizzare una parte di fagioli interi guarnizione e la restante passarla al passatutto. In fase di guarnizione utilizzare il peperone crusco.

It turned out quite well, all things considered. The sauce for the pasta had the slightest hint of anchovy and a somewhat stronger hint of red chili and the serrations of the pasta held it nicely. The cod/potato mash on top of the bean puree combined for a flavor I had never experienced.

But this is only part one. The real delicacy from the menu I am excited to make, Zuppa dei Brigante (“Brigand Soup”) awaits. For now, though, I have a flight to Italy to catch. Ciao!

What we talk about when we talk about smart cities

About a century separates the two Scientific American covers above. We’ve been talking about “smart” cities for a long time.

Maybe not in so many words, but the idea of designing a city to optimize it, to make it more efficient, to make its uses more intelligent far pre-dates digital technology. Sometimes the term is at the forefront of urban rhetoric and marketing — during election cycles or after natural disasters, for instance, or when new industry entrants smell a market opportunity.

And sometimes the idea recedes a bit. Recently we’ve seen outright hostility to “smart cities”.

But no matter when we’re talking about smart cities we often do so in terms of particular systems or projects. This city is smart because of its low-carbon transit network. This city is smart because of its waste-to-energy plant. This city is smart because of its predictive policing. And on and on. Or, as above, we can put together top ten lists of projects that will make your city smart. Projects that are so tied to specific new technologies they will either fail or be obsolesced by the volatility of technological change.

A more useful way to talk about smart cities might be to ask questions of a different type. What approach do they take? What is their philosophy of smartness? Who does it benefit in the long run? Below I describe some of these philosophies with design case studies. Though many of these examples are rooted historically, they are not necessarily linear in time — they overlap, circle back, and pop up dressed differently.

The clockwork city is the conception of metropolitan operations most familiar to people. It is an Enlightenment view of the city as a literal machine. One that can be measured, whose gears can be oiled, whose job it is to produce efficiency. It is an engineer’s view of what makes a city work. The city as sum of its infrastructure and services.

One way to understand the clockwork way of thinking is to use the example of public buses. A clockwork view poses the matter of buses as an exercise in operational performance: How can we manage our buses more efficiently? This of course has led to innovations such as timetables. It is an infrastructure-focused view that prioritizes the operator’s needs — essentially asking, in this example, how can we know when buses are supposed to be at a given stop?

There’s nothing wrong with this operational approach, of course, and indeed it has dominated city management for a very long time. What’s useful is to note how this view is the singular focus of most modern “smart city” campaigns, especially with regards to how enterprise technology firms view the challenges in front of a city. Wanting to know where your buses should be is the seed that grows into citywide command centers powered by top-down, command-and-control technologies (such as the one pictured above in Rio). It has been called Dashboard Governance.

There have been many attempts at this kind of smart city. Most are developments from scratch or adjacent districts of established towns. Because ecological sustainability is in theory a more easily quantifiable axis of a city than, say, homelessness or income equality, energy is usually the centerpiece of these types of smart cities. Most have not lived up to their marketing.

There’s a different philosophy of the smart city and it has been driven by the move in recent years to open up city data to the public. Initially undertaken as a political corrective to decades of opaque systems and hard-to-FOIA documents, the open data movement in cities has grown beyond transparency to cities that use it to enforce accountability in its workforce, to analyze patterns and trends for policy interventions, and even as a starting point for companies to add valuable services upon. Open data as economic development.

Using the bus analogy again, instead of the city telling commuters when a bus should be where, an open city approach to design let’s people ask: How can I know where and when a bus will be available? It may seem a subtle distinction, but the difference is enormous. The open city puts the user of the system — in this case the city-dweller — at the center. Decision-making control, if not operational control, of the system moves from inside government to outside.

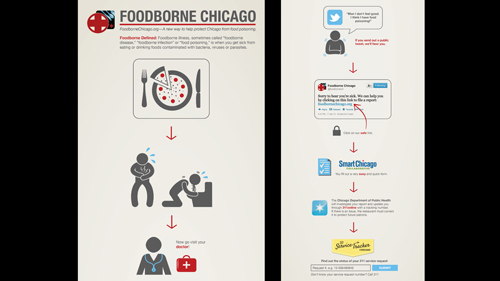

Examples of open city design from the civic tech movement are plentiful. Above, Foodborne Chicago uses public tweets (generated by people totally unconnected to the public health department) to determine whether an instance of food poisoning has occurred.

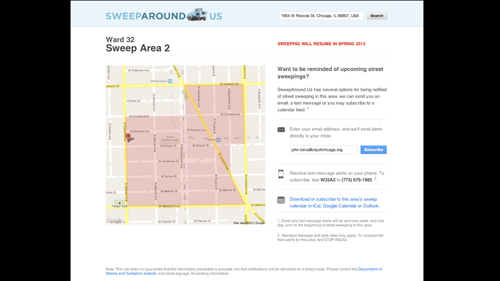

SweepAround.us takes somewhat inscrutable public data about when ticketing will be enforced for street cleaning and proactively alerts residents when they need to move their vehicles.

The open philosophy of the smart city above all focuses on making the city more legible; it isn’t necessarily about citizen-government interaction but about allowing those who live in cities to situate themselves at the center of systems — making sense from the vantage of their personal needs and uses.

The newest perspective is what might be called the emergent city. In this framework initiatives are aimed at changing the underlying conditions that lead to a system’s functions, rather than the system itself. It takes the constituent pieces of the urban experience (whether run by the municipality or not) and joins them loosely through technology to generate different outcomes.

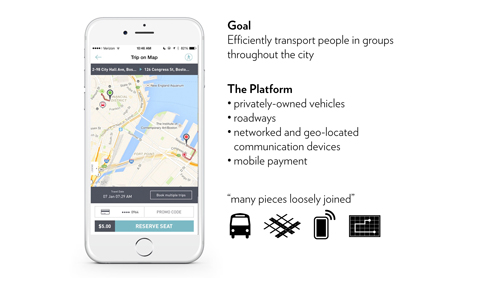

The bus example is again useful. An emergent approach, one that we might also call city-as-platform, asks not when or where a bus is, but rather “What if any vehicle could be a bus?” Typically cities address outcomes, in this case moving people around, but emergent city design seeks to change the initial parameters of a system and let complexity grow from that.

If the goal is to efficiently transport people in groups throughout the city, a centralized bus service is one way to do it. But thinking of mobility as a platform, we can also tally the constituent parts — here, privately-owned vehicles, roadways, networked personal devices, and mobile payment — and ask how they might be made to generate the same outcome as public buses. The example of the Boston company Bridj above is one effort at accomplishing this.

This isn’t about privatizing services so much as it is rethinking a city’s assets — public and private — when overlaid with network technologies. It’s the “sharing economy” with a civic bent: what happens when urbanism focuses on recombinant uses of space and infrastructure. A technologist might call it experimentation-as-a-service.

Projects such as Hello Lamp Post out of Bristol, England have this philosophy in mind as it uses street furniture to prompt local, place-based storytelling. The addition of network technologies to traditional aspects of the cityscape is what allows for the emergence of new uses of the city, new behaviors for its dwellers.

While IT companies push for Internet-aware devices (the “Internet of Things”) largely in the pursuit of operational (clockwork) efficiency, the networked city also offers the possibility of new bottom-up solutions. The Array of Things is a non-governmental project aimed at providing hyperlocal environmental data to whomever wants to use it. (One envisioned use case is to provide information about ice patches that have formed on sidewalks block-by-block.) In both examples, what’s different is that traditionally monolithic infrastructure is atomized and offered up for reuse. Hello Lamp Post and the Array of Things are not solutions to city challenges per se. They change the initial conditions of a system, allowing complexity and the creativity of the urban populace to make something from them.

It’s tempting to think of these three frameworks as evolutionary, one building upon the other. But they are not. There are aspects of all three consistently rubbing up against one another in most cities today. And it is difficult to categorically say that one view is better than another, for that distinction requires acknowledging who the approach benefits. Being smart about smart cities requires asking ourselves who is defining what smart is and who might be sidelined by that definition.

Hive architect

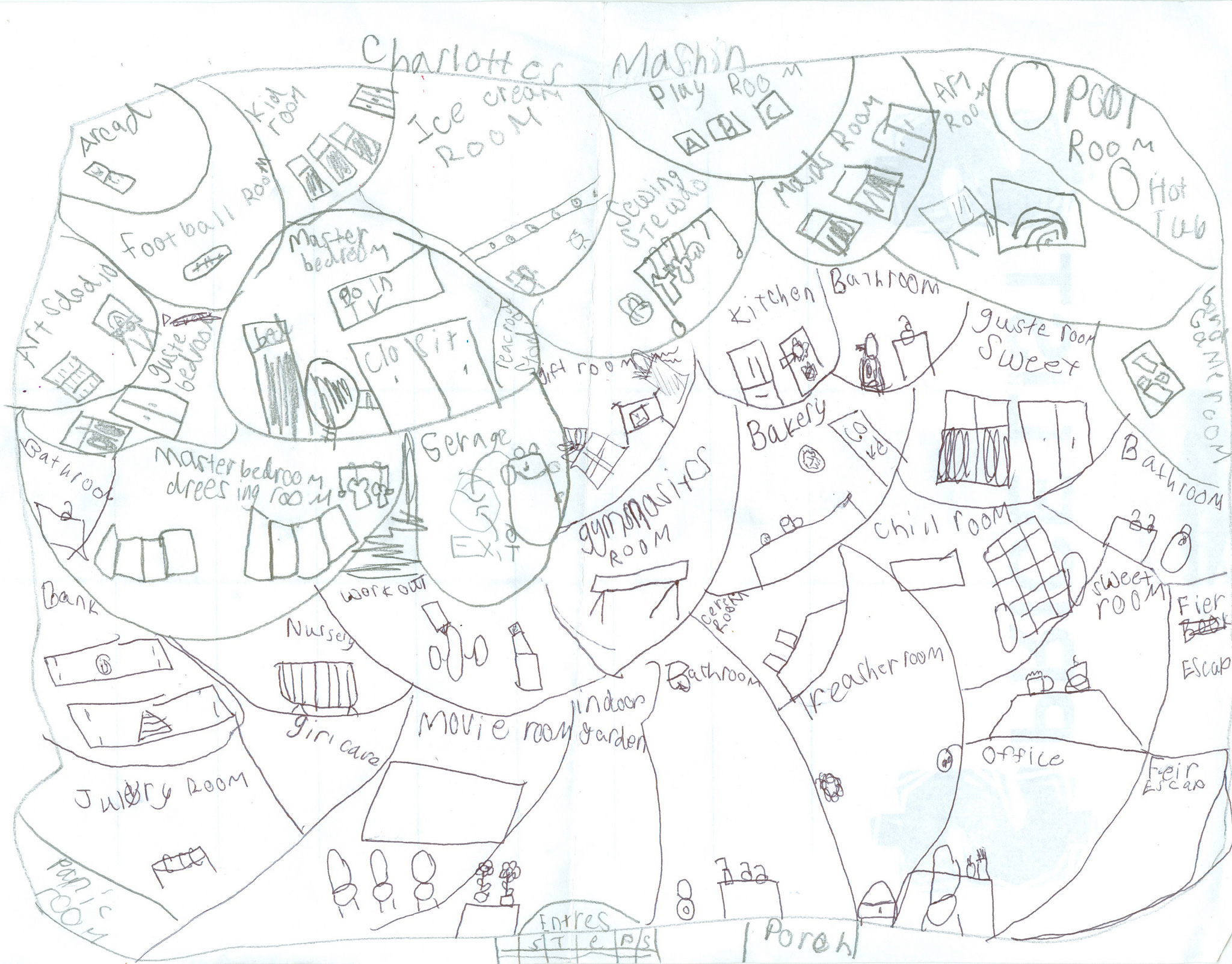

My daughter is obsessed with designing houses, architecturally. I love it, but there’s room for logic of any kind improvement.

Notes:

- Natural light? This architect is not a fan.

- Panic Room on an outside wall = security problem!

- Somewhat uneven distribution of Fire Escapes (and it’s a one-story house).

- Garage in the middle of the house is accessed via an “underground tube”.

- The house has its own Bank, which is not to be confused with the Treasure Room.

- Girl Cave!

- Two Art Rooms, presumably in case one is filled with terrible ideas.

- No Kitchen, but it does have a Bakery, Sweet Room, and Ice Cream Room. UPDATE: I missed the kitchen. It’s there!

Click image for larger version.

Looking for a house manager/nanny

We’re in the market for some help. If you fit the description below or know someone who does, please get in touch.

Busy Roscoe Village family seeks energetic, experienced, self-directed full-time house manager.

Individual should be a non-smoker, have own transportation and mobile device, and be comfortable with email, texting, and web-based services (e.g., classroom websites, school lunch ordering, activity registration) necessary to run this active family. Three children, ages 8, 11, and 13, are in school full-time M-F, but need after school care. Full-time working parents need help managing the house.

Flexibility to run errands, willingness to perform light housekeeping and organize small projects, and ability to maintain active extra-curricular schedules for the kids are a must. 40-45 hours/week, split between time with children (school dismisses 3p, most days) and time to help around the house and run errands.

Daily hours have flexible start time, and parents cover “morning shift” most days. Ability to work longer hours or overnight when both parents are traveling, or entire days (when school is out, or kids are sick) is optimal.

If you fit this description, are available immediately, and can provide strong references we look forward to hearing from you!

Giftmix 2014

Some select tunes that I enjoyed this year. I hope you do too. Happy holidays and a healthy, prosperous new year to everyone.

Tolva Giftmix 2014 by Immerito on Mixcloud

Hawkmoth – Plaid

Awake – Tycho

minipops 67 [120.2] [source field mix] – Aphex Twin

I Take Comfort In Your Ignorance – Ulrich Schnauss

Quincy – Deep Dish

Pole Position (Gran Prix Version) – Der Dritte Raum

Higher Ground – TNGHT

Canis – Theorem & Sutekh

Mimas – X-102

101 rainbows ambient mix g1 – Caustic Window

Full stream at Mixcloud, above. File for download here (114MB). Previous mixes here.

Spaceship! Spaceship! Spaceship!

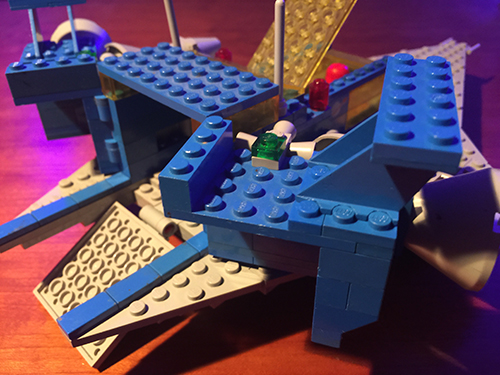

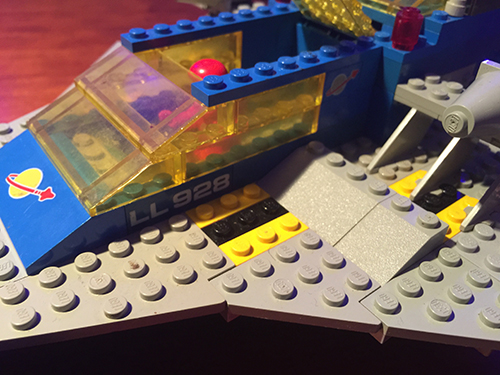

A few notes on rebuilding my first LEGO set from 1979.

I set out to build the iconic, genre-defining LEGO Galaxy Explorer. I knew I had the original pieces as I have every brick I was ever given, bought, or bought for my own kids. There are tens of thousands of pieces in several bins full of 35 years of detritus that inadvertantly got mixed into the slurry. Batteries from the 1980’s (long since having leaked their acid), various mementos, trash, thumbtacks, model pieces, indecipherable bits of toys and games, sharp shards of pieces long since stepped-on and cracked. Finding the original bricks was part autobiographical archaeology, part that Russian Roulette scene with the log creature in Flash Gordon.

The LEGO Galaxy Explorer jumpstarted the “Classic” phase of space-themed brick sets. Before dueling factions, before space police, before aliens and whatever the hell Bionicle was, Classic Space was about exploration, period. It’s interesting to read the set as a kind of cultural document for the vision (perhaps a Danish vision) of what spaceflight was or could be in the late 70’s.

Apollo was over. Skylab had just plummeted back to Earth. Salyut 6 still orbited. And the Space Shuttle was in testing for its maiden voyage. Clearly the shuttle was an influence on the Galaxy Explorer: both have fixed wings and separate crew and cargo compartments. But exploring the design of the brick ship suggests that the new NASA orbiter was not its only inspiration.

The Galaxy Explorer is the threesome lovechild of a Space Shuttle, a dump truck and a Harrier jet. How else would you explain the loading ramp in the back which really only works in gravity where you can cart things up? Or that, without wheels, the ship clearly does not take off like a plane. The underside engines are obviously for vertical ascent. And if you got those, why do you need wings at all?

The answer is what makes LEGO such an incredible company: the design of the ship is as influenced by how human beings play with interlocking bricks as it is by actual spaceships. It’s the difference between LEGO and model kits. For one, kids play with LEGO bricks in an environment with gravity. They might fly the ship in their hand through the air, but actually interacting with it takes place on some surface, orbital mechanics be damned. This explains the loading ramp (kid drives LEGO car around on a surface and into the ship) and the vertical take off (kid grabs the ship and yanks it up), and even the wings (that’s how the kid holds it). It’s a very planet-based (or at least surface-based) view of space travel, because that’s how (and where) kids play.

Play as primary design driver is evident in an odd little locking piece that keeps the cargo bay doors from flying open. It is one of the rare instances I know of where a piece is added simply for convenience of real-world usage. The 1×2 flat blue piece has no aesthetic or functional value on the ship-as-ship, only for ship-as-plaything. Take that, fourth wall!

Then there’s the ornamental, gaudy and inexplicable: racing stripes (huh?), logos, vents, fuselage arrows (for ground crews?) and livery numbers. No decals, thankfully. The whole thing was driven by an actual circular steering wheel (something even airplanes don’t use). Maybe the ship never did leave the ground: the minifigs have visor-less helmets and zero protection from the (lack of) elements other than their spacesuits.

It’s the color scheme, though, that defines Classic Space for me. Gray base plates and horizontal surfaces, blue structural elements, translucent yellow windows. Toss in a few computer bricks (oh, the computer brick!), a radar dish, and some green and red see-through 1×3 cylinders — that aesthetic shaped my LEGO creations for the better part of a decade. (Green? There is no green in space.)

But there is yellow. As in yellowing pieces. Though I was fastidious in making sure I found ever single correct piece — never substituting or otherwise being clever — I obviously did not find all the original pieces. The slight yellowing (and relative state of cruft accumulation) on some of the bricks is a dead giveaway. I bet 30% of the ship is original. I kinda like it actually. The original Star Wars showed us how cool beaten-up, dusty and old space could be. My LEGO Galaxy Explorer wears the patina of time well.

If you’ve seen The LEGO Movie you have witnessed the legacy of the Explorer. The character Benny maniacally flies around yelling “Spaceship! Spaceship! Spaceship!” in a craft that is clearly inspired by the original set. It’s over-the-top, but retains the rough geometry, retro rockets, racing strips, and (maybe) the cargo bay. In a nod to dorks like me in the film, the actual spacesuited character is cracked and clearly worn through time.

Sometimes the future is nostalgia.

How to dump accelerant on the Great Chicago Fire Festival

The reports say there were 30,000 people hugging the Chicago River between State and Columbus last night to witness the first ever Great Chicago Fire Festival. That’s a low count and it doesn’t capture at all the sense of anticipation and excitement that suffused the crowd — something I cannot ever remember witnessing in the Loop proper on a (chilly) Saturday night. People were ready and proud to be part of a great spectacle.

This did not happen. Most of the morning-after reviews cite technical glitches in actually getting the floating set pieces to ignite. Social media, of course, was less kind — and funnier — dubbing the event “The Great Chicago Smolder Festival”.

I was disappointed. It’s not easy to haul a family of five into the welter of downtown on a Saturday night. But like everyone else, we had high hopes.

And I still have high hopes. I’m not giving up on this festival — and I hope the City, Redmoon, and the funders behind the event don’t give up either. I want to be excited to take my family to the Loop. I want to celebrate our history with tens of thousands of fellow Chicagoans. I want to see the the river blaze.

Here are a few suggestions on how to make this happen.

- Make the spectacle move. Chicago is good at parades. Really good. Why not treat the spectacle on the river as a parade? Not just the floating choir (which was fantastic) and the kayaks, but all the showpieces. There’s no perfect vantage point on the river, especially with its bend at Wabash, but there’s no perfect vantage at a street parade. This is why it moves.

- Use the cityscape. The buildings, bridges and embankment along the river are ripe to be used as part of the show. Many more people can see them than can see the surface of the river. They are tableaux ready to be illuminated, projected onto, or used as screens showing the current action. (Sydney, Australia has this figured out perfectly in its Vivid Festival.) Let’s not let the garish Trump sign be the only thing we see when we look up from the waterway.

- Shut down Upper Wacker Drive. Obviously the City underestimated the turnout, but that’s a good problem to have. In the future, use Upper Wacker as a pedestrian zone. More room to move along the river, more food truck and vendor stall space, more of a street festival atmosphere. Traffic can be conveniently re-routed to Lower Wacker.

- Establish better viewing infrastructure. At Mardi Gras New Orleans lines Canal Street with bleachers. Some version of this is needed along the river for future fire fests. Very few people not in the first row at any given vantage could see anything except others’ glowing smartphone screens held up in the air. And with people scrambling and dangling all over the embankment infrastructure last night this is as much a safety issue as it is convenience. The new riverwalk will help with viewing, no doubt, but there still needs to be smart planning.

- Less pandering prologue. More spectacle. I get that you have to thank sponsors, but the narration at the show’s beginning delayed and defused much of the crowd’s excitement. And if you are going to make shout-outs, let’s not get carried away with the politicians and city staffers. The show is for regular Chicagoans. At the very least start the show with a bang and then chatter away for a bit.

- Remember that the larger the stage the less nuanced you can be in your storytelling. I love all the little nods to Chicago history embedded in last night’s event. It’s great to learn about this in promotional material. But the actual event — which is not intimate like a theater — is not the place to be subtle. Go big or we’ll go home.

- All the flaming things. Let’s be honest with ourselves here. It was not Chicago history or fireworks or the promise of food trucks that brought all these people downtown. It was fire. A great floating conflagration (with explosions!) was the real thrill we sought. I understand there were technical problems, but my sense is that even if the three buildings had burnt in unison they would not have blazed as mightily as people wanted. The river canyon is all about verticality. Next year we need flames several stories high.

So let’s treat this one as a dress rehearsal, come back next year, and really create an inferno.

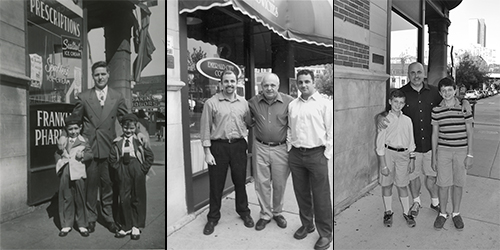

Intersections in space and time

Sometime in the late 1940’s my grandfather, Eddie Tolva, took his two sons — my father and uncle — to the corner of Dakin Street and Sheridan Road and someone snapped a photo. Just three blocks north of the Wrigley Field scoreboard and nestled between a cemetery and a westward jog in what is now the CTA Red Line elevated tracks, this was the corner of the sleepy little street that my dad grew up on.

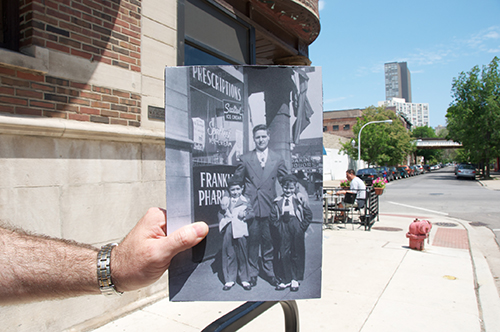

When I first moved back to Chicago in 2000 I spent a considerable amount of time trying to find the location of this photo. I knew the neighborhood generally (what is now known as Buena Park, part of Uptown), so I just rode my bike looking for the few architectural elements contained in the photo. Eventually I found the building — 3936 N. Sheridan — and, in 2003, got my brother and father together to re-enact the shot. What was once Franklin Pharmacy was then Emerald City Coffee. The proprietors told us that the corner shop had been many things over the years including a pet shop and a porn store.

A few years later I returned with a friend to try my hand at the photo-in-the-real-world perspectival trick (part of the fun “Looking Into The Past” Flickr group).

This past weekend I took my family back to the corner, completing a three-generation sort of family placemaking. Here’s a larger version of the triptych I put together. (And the complete album.)

There’s a plaque on the masonry of the building right at the spot of the photo which reads “On this spot in 1897 nothing happened.” Who knows who or why this location was chosen for the pseudo-historical marker, but I do enjoy the irony that this particularly meaningful spot in my family history is demarcated by a sign like that.

The building itself may not be there much longer. Its owner wants to raze it for an 8-story transit-oriented residential complex. But the corner will always be there, my family’s little locus of reference in the middle of an ever-changing city.

The natural proprietors of the street

A while back Iker Gil of Mas Context asked to interview me for an issue of his magazine focused on the topic of surveillance. The angle was to present data, especially urban data, through the lens of “tracing, archiving, control, camouflage, deletion and monitoring”. The topic was very relevant, given what we know about the NSA and PRISM, but something about the issue’s sole focus on deliberate subterfuge and power imbalance rubbed me the wrong way. I noted to Iker:

“[S]urveillance” is a word fraught with bias towards the act of looking, covertly. What’s going on is much more than that: sensing of all the vital signs of the environment, not just looking at people or their data. That may be what you intend, but it is a partial and distorted picture of the value of instrumented cities. It does not imply any of the benefits of bus trackers, or dynamic tolling, or bridge traction coefficients for warming or any of the other myriad ways the Internet of Things makes our lives better.

Iker was interested in speaking with me based on my advocacy of — and work towards — platforms of public data collection and sharing. I agreed to be part of the issue mostly because I wanted to make the case that there’s nothing inherently nefarious about city data. There’s a line between observation and surveillance — and it needs to be well-limned. Sensible, adaptable urbanism is based on thoughtful observation. Mas Context chose to go with surveillance, which is useful: knowing what’s on the other side of the line is important in being able to draw it accurately.

The full piece is available here.

Cities teem with data because they teem with people using the city. Records of its use — from historical real estate deeds to real-time pedestrian-counting — is data collection. Naturally, news organizations, community groups, activists, and municipal governments have been collecting it for a very long time.

But that’s not the important point. What matters is how it is collected and shared. Collective observation is achieved — and surveillance defused — when the following goals are achieved:

- individual privacy is protected

- the act of data collection is fully transparent

- all collected data is made available openly, free of charge, and in formats that are useful

Drop the ball on any one of these and you have what can rightly be called surveillance. Nail all three and you get what Jane Jacobs called “eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street.”

It’s that second clause — who the eyes belong to — that’s the critical difference. Being looked at (and perhaps not even knowing it) versus doing the looking yourself.

Healthy neighborhoods are those that feel observed (and hence engaged) by its residents. Safe roads are those where everyone — motorists, cyclists, and pedestrians — is equally vigilant. Smart cities are those where people are in the know, period. This can come from a mix of their own observation, a diligent local press (and blogging) corps, and, yes, data that is published about their world collected with notification, openly, and with utmost respect for privacy.

Healthy urban experience depends on eyes upon the street. Let’s make sure those eyes are ours.

“Your moon is on fire”: design and city-making in Helsinki

A few weeks ago I had the pleasure of visiting Helsinki, Finland as a guest of Pluto Finland and Forum Virium. It was a trip long in the making, as I had been extended an invitation by the mayor of Helsinki, Jussi Pajunen, almost two years previously in my role at the City of Chicago. I knew something good was afoot there, so it was time to figure out just what exactly.

Purely by coincidence I was in DC the days before departure and received a tour of Finland’s incredible embassy there. This is not your normal Embassy Row structure. Cantilevered over Rock Creek Park, the building is airy and expansive, feeling almost as much a part of the forest it backs up to as a portal to it. In fact, the grid of the floor plate is “extended” into the trees by way of light-topped poles that repeat the spatial divisions of the interior. It’s a natural-architectural harmony that, one would guess, also underpins the Finnish government’s successful attempt to build the first LEED-certified embassy in the US. Nature as design inspiration and constraint — a theme I’d see repeated many times over the next week.

My exact point of departure was Dulles Airport, the masterful sloping tug-o-war-of-a-building designed by Finnish architect-hero Eero Saarinen. It’s gorgeous and evocative of flight — or at least ascent. Like his arch in St. Louis, which I frequented during my time in graduate school there, the design is a simple curve set against the sky. At Dulles the slope takes humans from ground to the clouds; in St. Louis the Gateway Arch plants the dreams of westward expansion back on earth.

(I thought also of a third curve, not sloping up or down but across: the facade of Saarinen’s IBM building in Yorktown Heights, NY, where I spent much of my early career. The Yorktown building’s architectural conceit is not about bringing people to or from the sky but into contact with one another: no office has an exterior window; the only way to get anywhere or any sunlight is to engage with the hallway formed by the long, gently curving facade.)

All of this an unexpected prologue to the trip. Finnish design escorting me out the door.

Helsinki was named the World Design Capital in 2012. There are many reasons for this honor that have nothing to do with the built environment, but the city itself feels well-crafted, smoothed-out, intentional. New on the scene as a European capital, relatively speaking, Helsinki is a modern city that bears the imprint of what we’d only later call urban planning. That there are very few iconic elements in its cityscape — an Eiffel Tower, a Ponte Vecchio, a Big Ben — focuses attention on the entirety of the place as a designed object.

But there’s also an urgent pragmatism at work. Dan Hill, in his fantastic essay “Designing Finnishness“, describes it as such:

Necessity does not breed frippery, skittishness or carelessness. It breeds purpose, momentum, independence and a belief in technical strength—the art of know-how, nous, savoir-faire.

Necessity, this particular mother of invention, is the challenge of living in such a harsh winter climate, with a gargantuan landmass, minuscule population, and traditionally bellicose neighbors. To survive any of these means being smart and deliberate about how things work. At the urban scale this is about the beauty of efficiency.

Helsinki panorama from Hotel Torni (by Tor Lillqvist)

Helsinki was recently recognized as one of six exemplar “smart cities” in an EU Europe 2020 report which defines a smart city as “a city seeking to address public issues via ICT-based solutions on the basis of a multi-stakeholder, municipally based partnership.” If this is the litmus test for smart by European standards I saw plenty of examples of why Helsinki qualifies.

The municipal government — which provides nearly all public services short of police and military — has moved far beyond the policies and portals of open data of its Western European counterparts. Nearly everyone I talked to, including deputy mayors Hannu Penttilä and Pekka Sauri and the mayor himself, was keen to show me the applications that have been built upon the Open Ahjo API for accessing materials related to the deliberation of procedures and laws. Put another way, Helsinki has an open API for the process of democracy rather than simply a portal for the results of it. This is a huge deal: debate transcripts, legislative emendations, recorded minutes — all synchronized and designed for ease-of-access and cross-reference. It’s a real-time wiki for how city government is making decisions. This is what open data in the US needs to aspire to.

How’d they get to this point of extreme transparency? I have no definitive answer, but it doesn’t hurt that Estonia and its capital Tallinn right across the Gulf of Finland is a champion of digital government. While there’s a history of affinity and commerce between these two cities, you get a whiff of competitiveness when Finns note that for Estonia, who long suffered the very opposite of open government under Soviet occupation, “it is easy when you start from nothing”.

Data, not just transcribed conversation, is the bedrock of a city that seeks to be a platform for innovation outside of government. And Helsinki leads in that arena as well. They actually have a department called Urban Facts, which would be funny if it weren’t so good at what it does. More important — certainly more worthy of emulation — is the Helsinki Region Infoshare portal. All cities exist as part of metropolitan regions; data does not stop at jurisdictional borders. While the Infoshare does not normalize data across cities, it does make it easily accessible — a first step to the real win of data standards between cities.

The key in the EU definition of smart city, above, is “multi-stakeholder”. The first wave of smart city rhetoric focused on government and infrastructure, almost as closed systems, enterprise and top-down. But what’s clear to nearly everyone actually involved in technology for cities is that it’s actually innovation outside (sometimes just on the periphery) of government that effects the real change. But that swirling mass of talent and activism outside government often needs a center of gravity. In Chicago that’s the Smart Chicago Collaborative; in Helsinki it is Forum Virium, specifically their Smart City project area.

Forum Virium serves an important role of organizing the various communities involved in digital city-making. Led by the polymath dynamo Jarmo Eskelinen, Forum Virium is part matchmaker, part grant-seeker, part center of knowledge for all things smart city.

One project of real note under Forum Virium’s purview is the Kalasatama smart district project. One of several brownfield waterfront in-fill projects in Helsinki (heavy shipping has mostly moved to other areas in the region), Kalasatama is the testing ground for new technologies in the urban fabric. Unlike first wave smart cities like Masdar and Songdo, however, this district is right in the middle of Helsinki. The project, called Fiksu Kalasatama, aims to improve energy consumption, transportation and social services through integrated systems and ease-of-access and, while, it is early in the planning phase, it is clear that the goal is to serve as a pilot for scaling into Helsinki proper.

Creative Finnish city-making sometimes has no digital component at all. Would you believe Helsinki is the epicenter of wooden skyscraper design? That’s right, wooden. And tall. The huge swath of forests north of Helsinki created a world-leading paper and pulp industry for decades in Finland, but the rise of online communication is forcing major timber companies to rethink the end-uses of their product. The paper company Stora Enso is currently developing Wood City, an entire district in the city built of timber.

Chicago, you may know, has something of a history with crappy, flammable wooden structures — so the idea of Wood City at first gave me pause. But I was impressed by the engineering and science behind the plans for construction. Wood of course burns, but, as was demonstrated, when subjected to flame cross-laminated timber essentially chars a protective cocoon around the structure-bearing beam at the core.

There are many appealing architectural and sensory (olfactory!) implications of very large wooden structures, but perhaps the most important is that wooden structures are far more malleable over time than steel and brick. Stewart Brand’s notion of a building’s “shearing layers” — its site, structure, skin, and services — that all evolve at different rates has long been fundamental to smartly-designed buildings. There’s something very code-like and mutable about a building as open to modification as those Stora Enso is constructing. (It’s no wonder shearing layers has been adopted as a concept in software too.) Nature here not so much as design constraint as advantage.

In Espoo, a large suburb of Helsinki best known as the home of Nokia, I had a chance to visit the UrbanMill (speaking of shearing and timber, ahem). UrbanMill is an incubator for startups focusing on civic innovation. It’s a sign of some maturity in the Finnish startup ecosystem that something as specialized as a city-focused startup space even exists. There are very few in the US, but the opportunity space is huge.

What’s exciting about UrbanMill is less its projects, which are excellent, but that the startup energy in Helsinki is off the charts, evident most proximately by its next-door neighbor Startup Sauna. Rovio’s Angry Birds and Supercell’s Clash of Clans are two of the most successful examples, but tech-savvy entrepreneurs are pouring out of Helsinki’s universities and into other application areas as well. If even a fraction of these folks choose to tackle the problems inherent in cities — mobility, social justice, public safety, the list is endless — Helsinki will have a leg up.

The Microsoft acquisition of Nokia was finalized while I was in Helsinki. Time will tell how this merger turns out, but history suggests it won’t be easy for the Nokia brand to thrive under Microsoft’s stewardship. And this, ultimately, is a good thing. The effect of Nokia on Helsinki is tangible — I’ve never, for instance, seen so many people using Windows Phones — but it has also been an enormous magnet for technical talent in the region. That magnetism is weakening which means more opportunities for engineers and computer developers to join smaller firms or start their own. It’s time for new centers of gravity to form in Helsinki’s industrial galaxy. This can only be good.

Helsinki was a lot of fun too. I happened to be there the week of one of Finland’s biggest public holidays. Called Vappu, May Day elsewhere, it corresponds to the graduation of thousands of Finnish high school students. On the eve of Vappu the central plaza of Helsinki fills to capacity to watch the tradition of “crowning” the statue called Havis Amanda with a university cap (looking somewhat like a sailor’s hat). At that point everyone else is obliged to put their university caps on (including people who graduated decades ago) then basically spend the next 36 hours drinking, picnicking and making merry.

I was also honored to be invited to DJ “Chicago Night” at a local bar on Vappu eve eve. Coming the week after Frankie Knuckles died, you can imagine the playlist.

I cannot not comment on the beauty of the Finnish institution of saunas. The basement of the embassy in DC is a vast, gorgeous sauna (the only Finnish word in English parlance), where the ambassador holds official meetings. At the Kotiharjun sauna in Helsinki I had the privilege of meeting with the incredible Open Knowledge Finland group. Casual, public meeting places like this are, alas, on the decline in Finland, primarily because new residential development almost always allows for in-unit or shared-unit saunas. This is a shame as the sauna as a social institution is an incredible social equalizer. Everyone is the same when they are sweating, hardly breathing, and nude. A lesson for city-makers, indeed.

My visit to Finland came a few weeks after a similar trip to Italy. The contrast could not have been more stark. Fiery, mobilized, sometimes angry Italian civic innovators railed against a common cause — usually the government itself. I didn’t see that in Helsinki. Government seems to be running just fine. The leaders get open data and government and seem to fairly finely tuned into the urbanist needs of the city itself. And so I was left wondering: isn’t part of the appeal of a city the resistance in the material, a little bit of grit in the gears? Real creativity is born of friction — psychological, sociological, political. Beyond surviving the climate what is the passion that stirs Finns to design what they do?

I do not have an answer to this. I was there less than a week. But I would love insight. I do know that the primacy of design in urban matters as a counterbalance to tech-heavy “smart city” rhetoric is welcome. We won’t get to truly smart cities with engineering and computer science alone. It takes “the art of know-how, nous, savoir-faire” as Dan Hill put it, something designers excel at. Finland can be the vanguard of the second wave of smart cities.

A note on the title of this post. The week after I was in Helsinki this tweet came through, which pretty aptly summarizes the inscrutability of the Finnish language. I can fake my way through most of the Romance languages. But Finnish, forget it.

Crash course into Finnish language via @Me_Pia1 #Finland #Finnishlanguage #visitfinland pic.twitter.com/BeIoN7oFdB

— Visit Finland (@OurFinland) May 13, 2014

Helsinki’s moon, Nokia, is on fire. But the city’s skill at design, experience in open city government, and activated civic actors outside of city government form a bright sun. One hopes that the almost-perpetual summer sun in Helsinki is a metaphor for things to come.