City of Big Data

Newcity has published an edited transcript of a conversation I had with writer Phil Barash about design, data, and urban systems. It’s a lotta words, but does, in a way, capture more fully my thinking on data-informed urban design than anything that’s previously been published. So I’m glad for that.

Here’s the full piece: Bright Lights, Big Data: How the Hog Butcher became the Data Cruncher.

The story is timed to coincide with the opening of the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s City of Big Data exhibit. If you live in Chicago — or are visiting (the CAF architecture river cruise is the most popular thing to do in the city) — you really should check it out. Answer questions such as: What does information architecture have to do with the built environment? How did the fire of 1871 kick off Chicago’s obsession with urban data? And, just what in the hell does Carl Sandburg have to do with big data?

Bonus: it features a 3D-printed monochrome cityscape used as a “canvas” on which data visualization is projected. Spectacular, immediate, and physical.

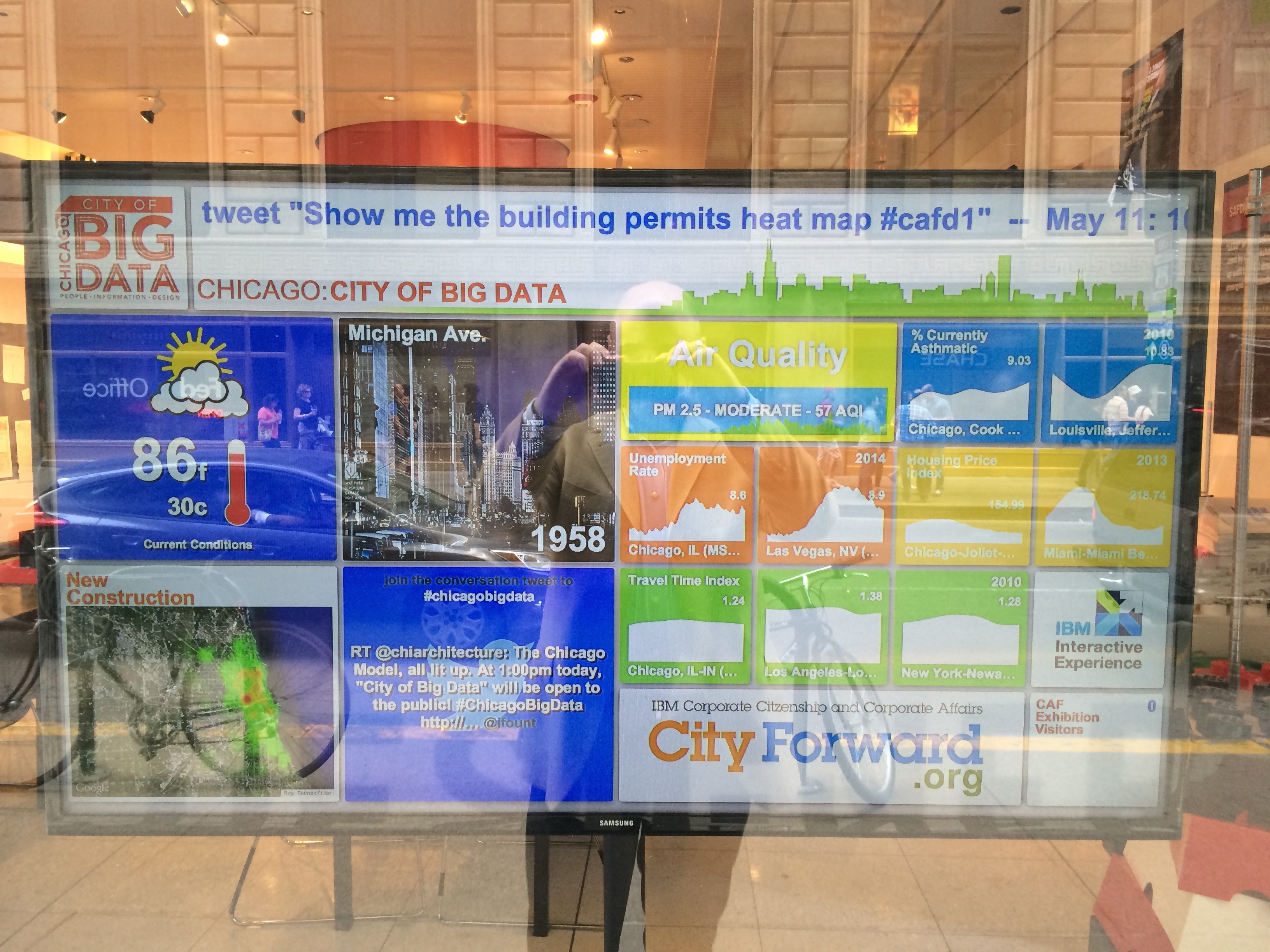

The exhibit also features a custom dashboard of city vital signs, developed by my old IBM City Forward team. Two special panels face Michigan and Jackson for data-flâneurs and other passersby.

Optional caption of above photo: self-portrait with all professional pursuits to date, 2014.

Notes on a “smart” tour of Italy

I’m recently back from a short tour of Italian cities — Milan, Turin, Rome and Florence — where I met with entrepreneurs, company leaders, academics, and government officials on the topic of “smart cities”.

The term “smart city” has received some cogent criticism of late. (See Greenfield and Townsend.) It’s a marketing buzzword that’s become a policymaker catchphrase and, at least in the United States, is met with whatever just precedes skepticism. But elsewhere in the world, the phrase seems earlier in the hype curve. The overwhelming sense I got in Italy is that “smart city” means everything — or possibly nothing — and is code for “what does technology mean for making our cities better?”

The simplest way I heard that question put was by an editor of La Stampa newspaper who noted that when the iPhone came out no one knew what “smartphone” meant. But now, as he said, everyone understands the difference between a feature phone and a smartphone. The implication was: when will we all have a common understanding of the “smart city”? Many city leaders wonder the same thing. I recently had a minister of a country ask me what software needed installing “to get a smart city”. /facepalm

Before attempting an answer at that let’s situate back in Italy. Italian cities are relative latecomers to the the open data/smart city/networked urbanism world. While European cities like Copenhagen, London and Barcelona race ahead it seems that Italian cities are only just embracing the concept. Many reasons were offered to rationalize this while I was there.

The first impediment, an entrenched bureaucracy with zero motivation to change the status quo, was the most common complaint, though I often thought of my own city — and its legacy of machine politics — as one example where the chief executive, in this case our mayor, confronted that bureaucracy head-on and was able to relatively painlessly make open government and nimble IT standard operating procedure within city government.

Leadership, especially at the municipal level where the reality of life is at its most immediate and the buck cannot be passed to a “lower” level of government, is absolutely critical. I saw this in a few cases in Italy. Mayor Piero Fassino of Turin seems to get it. Turin, like Chicago, was a town made prosperous through much of the 20th century by manufacturing. With its reliance on the automotive industry and the pressures of globalization Turin struggles, like Detroit, with market diversification and the cultural warping brought about by the primacy of the automobile.

But Turin seems to have turned it around. Downtown is as lovely as the pedestrian-friendly city centers of other Italian cities, finally, and their industrial base has turned their manufacturing excellence into an asset for branching into other fields beyond automotive. (In fact, the governor of Michigan was in Turin when I was there to figure out just how they’ve pulled it off.) Like Mayor Emanuel in Chicago, Mayor Fassino is a strong, nationally-known political leader who served in the central government for many years. His ties to the Italian parliament but singular focus on Turin has given rise to the most comprehensive smart city plan in Italy.

So, yes, leadership is key. But this is not a particularly useful insight. The question is: why are Italian leaders averse to embracing technology in the way that their other European peers do? What I heard, obliquely, is that the system is set up such that leaders endeavor to please their party rather than the civic populace. But how does this not characterize most political systems, the US very much not excepted?

The difference, I think, is a lack of critical pressure from outside of government. While I met with many civic innovators, activists and hackers, the groups seemed fragmentary — or, rather, without a real center of gravity. That center elsewhere in the West is almost always a fecund resource for building things, a ready supply of raw material — and it is almost always open, machine-readable, frequently-updated data about how cities are being used. The open data movement is nascent in Italy and this too is something that can really only be changed through political will and policy change. It’s the catalyst, the platform, for any smart city.

I also got an earful about the twin red herrings of open government: “What about privacy?” and “Won’t giving people data about the city create too much expectation for more?” These are both commonplace reactions and litmus tests for the fear attendant in political cultures who believe that information is the government’s to control, rather than the people’s to own. It is, after all, city-dwellers using the city that generates — and pays for — the data.

Privacy, obviously, is paramount — moreso in a world after Edward Snowden and revelations about the NSA. But Italy seems to have a handle on this, at least legislatively. One example: It’s been a few years since I was last in the country and I was struck by the amount of signage very forthrightly delineating areas of video surveillance. It’s actually somewhat gaudy, but all the signage suggests a culture at least activated about the implication of technology on privacy. If government can be proactive about alerting people to surveillance surely they can be thorough about protecting privacy in open data releases, the vast majority of which contains no personally identifying information whatsoever.

Challenges aside, Italy actually has much going for it. Culturally there’s a strong foundation for smart urbanism.

Italy basically invented urban planning, the architecture-like approach to city-scale layout that is at least nominally at the heart of urban planning today. Pienza, perched hill-top in Tuscany, is credited as the birthplace of Renaissance Urbanism and even today evokes a kind of civic intelligence that should be instructive as we move into overlaying networks on public space. There’s no reason Italy shouldn’t feel more than normally motivated to claim first place in smart urban design through technology.

Even when not centrally planned, the very age and unplannedness of Italy’s city centers lays out a path for smart urbanism. Narrow, labyrinthine streets may confound mapmakers, but they are the very essence of complete streets — a concept Italy has embraced since before it was a transportation engineer’s meme. Cities in Italian cores are open in a way that the “smart city” idea of openness ought to emulate. Americans may hate them, but the ZTL (Zona a Traffico Limitato) is a model for how municipal governments should treat the entire public way: access for everyone, including its non-physical vital signs like data.

Italy understands the power of design, period. And has built a global brand on it. Fashion is what’s most known, but let’s not forget the Renaissance and automobiles and the overall savoir faire of Italians in general. There’s no more ripe space to apply this distinct global advantage than in the service of Italian cities.

Italians love mobility. They may not have been the first in Europe with high-speed rail (though the Frecciarossa is pretty great), but who can deny that the culture of scooters and mobile phones — the latter of which was far more ubiquitous far earlier than any country I’ve ever known — doesn’t point to a citizenry ready for decentralized, data-informed urban life?

Italy perfected the city-state after Greek models and, as of the first of this year, the country is moving towards governance models that recognize the power of metropolitan regions at scale. The Città metropolitana changes to the Italian constitution amalgamate regional governance into 10 (possibly 14) conurbations. This bodes well for smart cities, since such are built on standards and interoperability between all players.

Opportunities are plentiful for smart cities specific to Italy:

- Transparency in a political culture tainted by high turnover and data opacity.

- Technology-enabled navigation where streets are a complex warren of restrictions and barely-Euclidean geometry. GPS just doesn’t cut it.

- Italian is one of the less-spoken European languages and yet their economy is fueled by visitors. This is opportunity for technology.

- As with most countries, energy independence has equal geo-politically importance with environmental stewardship. Italy’s historical manufacturing and engineering legacy can be retooled to capitalize on this new reality.

When I worked for the City of Chicago we never used the phrase “smart city”. As an abstract concept, it just wasn’t part of our day-to-day work. For one, cities can do smart things wholly apart from technology. “Open government,” “civic innovation,” even “networked urbanism” were what we called what we did, when we called it anything at all.

I was pressed in Italy to define “smart city” and the answer is that cities have always been smart. They are one of humanity’s greatest inventions. Italy especially has good examples of well-wrought, thoughtful urban experiences.

But the actual term of course has a valence today apart from this. Smart cities build upon the density, diversity, and proximity that characterize all great cities through sophisticated mechanisms of listening to their own vital signs. “Smart” here is self-awareness — whether through advanced, open sensors, policies of open data, or systems for citizen engagement. Feedback loops, abetted by technology, at hyperlocal resolution and close to real-time are the agents of diagnosis and change for the smart city.

Italy can make the leap — and in fact can capitalize on what has made it a center of urban innovation historically: design skill, organic urbanism, hyper-mobililty, and metro regional governance. “Smart” or not, it’s time to upgrade that urban feature phone.

Chicago’s Design 50

Photo by Joe Mazza

Despite the portrait of me in the piece (possibly the most unintentionally sad snap ever), I am very honored to be included in this list of designers in Chicago. Happier still that the definition of designer seems to be expanding.

Here’s the full article.

From City work to city work

Pleased to announce that I have recently joined PositivEnergy Practice as its president. PEP, as it is known, is a small engineering firm in Chicago that does big things — as in really tall and very complicated things.

I’m leading a group of talented engineers who design (and re-design) buildings, districts and cities. PEP’s speciality is high-performance, clean tech engineering focused on new structures, retrofits, and urban ecologies of infrastructure. Much of our work is done for — or in partnership with — architecture firms.

Exciting times, these. The tools of data analytics (and the open data itself pouring out of many cities) make this an optimal moment to bring performance simulation to a new level. Likewise, as devices and sensors proliferate throughout our urban areas design and engineering firms — who already understand complex physical systems and the human needs of the spaces they engineer — are well-positioned to potentially remake the notion of “smart” cities and infrastructure.

Crain’s has a short piece on this today as does the PEP website.

Woo!

When tech culture and urbanism collide

The city is the most complex machine ever invented. Running optimally the city generates opportunity and provides a platform for interaction, ideas, and improvement. As a concept the city has been iterated-upon, smashed and burnt to the ground, rebuilt, deliberately-designed, haphazardly-organized, and generally resilient for many millennia. But the city is still a human invention and every single one is flawed, many horribly so.

Which makes cities the ultimate problem set. For the engineering-minded and entrepreneurial the challenge of cities has enticed since the first itinerant merchants decided that they were no longer itinerant. Cities for centuries have been the locus of commerce and the crucible of invention (often from necessity). Demographically, they are on a path to be called home to 70% of the world’s population by 2050. If you want a market — or are driven by the moral imperative of figuring out how to get that many people to live in relative harmony — cities are your platform.

And yet some of our most creative problem-solvers — entrepreneurs and technologists who invent the things that have changed our lives radically over the last decade — seem not to grasp what makes cities so dense with opportunity in the first place. There’s a disconnect between the culture of technology companies and what makes for smart urban policy.

Recently SPUR‘s Allison Arieff noted the ways that tech companies have enthusiastically co-opted the language of urbanism — “community”, “the commons”, “town halls”, etc — while not actually embracing any of what that means in the real world. “Why,” she asks, “are tech companies such bad urbanists?”

The answer is that suburbia is in the very DNA of Silicon Valley, which makes it part of the genome of tech culture writ large. Though many of the biggest companies in tech now are less than ten years old, Silicon Valley itself came to be during the boom of late-20th century car culture. (The garage itself is mythical in startup lore.) Anti-density land use, zoning laws that abet sprawl, work-life patterns fashioned around automobile commuting — these traits are as central to Silicon Valley as Stanford, libertarianism and foosball.

Tech headquarters in the Valley (and many other places) are built as simulacra of cities. Corporate campuses sport their own transit systems (some of which venture out into the city itself, altering socio-economics in their path), bike share systems, restaurants, and health clubs. Facebook’s HQ even has a faux downtown, something straight out of a 1980’s shopping mall design handbook. Unlike a mall, though, none of this is open to the public. While “community” may be the buzziest of words in tech parlance, this is community-as-facade, a highly engineered experience that still revolves around automobile commutes and forecloses true serendipity. It would be funny if it weren’t such a problem: For all their embrace of futurism, tech companies in the Valley are merely recapitulating the failures of a bygone age of suburbia.

And yet San Francisco is the preferred place to live for many of these employees. Which is great, except that their salaries — out of synch with the communities in which they live — generate an economic force that skews rents, forces evictions and creates class stratification driven almost entirely by corporations not located in the city. It’s the reverse of a bedroom community. Wealth drives people into cities while keeping the engines of that wealth outside the city.

But this is 2013, not 1960. Today’s tech companies are not stupid. They understand the benefits of the city from a business perspective. (Which is why Amazon, Twitter and Zappos are all building headquarters in the middle of cities.) It is where the talent lives, its many modes of transportation chime with companies’ commitment to the environment and employee health, and cities are very often the conceptual blueprint for social innovation on the web, as Arieff points out. But understanding the benefits of urban life and attempting to create them as self-contained units that simulate a city — as much of middle America did in the latter half of the 20th century with gated subdivisions, office parks, and shopping malls — are two very different things.

Which is more than odd; it’s contradictory. The web itself, fount of so much innovation in the tech world, is the network embodiment of density, diversity and proximity — precisely the characteristics of cities. The sidewalk was the original social network; the corner store the original just-in-time retailer; the town square the original blogging platform. Given this symbiosis one would think more of an effort would be made in tech circles to understand the precepts of urban design.

——

So how do we change this? What might we do to set the sights of our smartest technologists towards sustainable urban design?

A start would be to remind tech companies of one of their core principles: user-centered design. Understanding city life means living city life. Not just commuting to it or from it and certainly not believing you understand a person’s situation just because you pass him or her on the street from time to time. The best products are those that begin with a user’s motivation and needs. They are empathetic applications. To crack the nut of urban-scale opportunity — and there is a lot of it, just look at the “sharing economy” successes of Uber, Airbnb, and Zipcar — technology must be built amidst the same forces that create the problems it is trying to solve.

And those problems must be meaningful and relevant to cities, per se. Nine times out of ten the first image in an ad or a presentation on the subject of smart cities will be of a traffic jam — as if congestion were the number one problem facing the city. It’s a very suburban view of what an urban problem is.

Is the self-driving car really what our rapidly-urbanizing world needs? Every single one of our ballooning population in their own hermetic cocoons? That too is a suburban view of the problem, a moonshot to an uninhabitable moon.

Vibrant, safe public spaces; shared, multimodal streets; exemplary education systems that propel people from early childhood through post-secondary; affordable housing — these are the issues that make or break cities. Or, put another way, these are the problems worth solving because they are worth a lot. Yes, in economic terms. Venture capital is all about risk and return. That risk (and potential incredible reward) is splayed out in every city in America.

To read certain of the screeds against the city (and responses to Arieff’s column) you’d think no entrepreneur or developer was having any success tackling urban opportunities. But that’s simply not true. We can build upon the success of the work being done at the intersection of technology and urban design, right now.

For one, the whole realm of social enterprise — for-profit startups that seek to solve real social problems — has a huge overlap with urban issues. Impact Engine in Chicago, for instance, is an accelerator squarely focused on meaningful change and profitable businesses. One of their companies, Civic Artworks, has set as its goal rebalancing the community planning process.

The Code for America Accelerator and Tumml, both located in San Francisco, morph the concept of social innovation into civic/urban innovation. The companies nurtured by CfA and Tumml are filled with technologists and urbanists working together to create profitable businesses. Like WorkHands, a kind of LinkedIn for blue collar trades. Would something like this work outside a city? Maybe. Are its effects outsized and scale-ready in a city? Absolutely. That’s the opportunity in urban innovation.

Scale is what powers the sharing economy and it thrives because of the density and proximity of cities. In fact, shared resources at critical density is one of the only good definitions for what a city is. It’s natural that entrepreneurs have overlaid technology on this basic fact of urban life to amplify its effects. Would TaskRabbit, Hailo or LiquidSpace exist in suburbia? Probably, but their effects would be minuscule and investors would get restless. The city in this regard is the platform upon which sharing economy companies prosper. More importantly, companies like this change the way the city is used. It’s not urban planning, but it is urban (re)design and it makes a difference.

A twist that many in the tech sector who complain about cities often miss is that change in a city is not the same thing as change in city government. Obviously they are deeply intertwined; change is mighty hard when it is done at cross-purposes with government leadership. But it happens all the time. Non-government actors — foundations, non-profits, architecture and urban planning firms, real estate developers, construction companies — contribute massively to the shape and health of our cities.

Often this contribution is powered through policies of open data publication by municipal governments. Open data is the raw material of a city, the vital signs of what has happened there, what is happening right now, and the deep pool of patterns for what might happen next.

Kicked off by data.gov and data.gov.uk, the open data movement has been replicated in most major Western cities. There’s no doubt this data has been put to good use by people and organizations outside of government. Chicago’s ecosystem of “civic hackers”, for instance, is unparalleled, generating hundreds of applications and analyses that make the lives of Chicagoans better. School data, lobbyist data, foreclosure, zoning and land use data, health atlases, snowplow-tracking data, real-time transit data, incarceration data, food-borne illness data — all these sets have been usefully translated into applications that change the way the city is used.

Tech entrepreneurs would do well to look at the organizations and companies capitalizing on this data as the real change agents, not government itself. Even the data in many cases is generated outside government. Citizens often do the most interesting data-gathering, with tools like LocalData. The most exciting thing happening at the intersection of technology and cities today — what really makes them “smart” — is what is happening at the periphery of city government. It’s easy to belly-ache about government and certainly there are administrations that to do not make data public (or shut it down), but tech companies who are truly interested in city change should know that there are plenty of examples of how to start up and do it.

And yet, the somewhat staid world of architecture and urban-scale design presents the most opportunity to a tech community interested in real urban change. While technology obviously plays a role in urban planning — 3D visual design tools like Revit and mapping services like ArcGIS are foundational for all modern firms — data analytics as a serious input to design matters has only been used in specialized (mostly energy efficiency) scenarios. Where are the predictive analytics, the holistic models, the software-as-a-service providers for the brave new world of urban informatics and The Internet of Things? Technologists, it’s our move.

Something’s amiss When some city governments — rarely the vanguard in technological innovation — have more sophisticated tools for data-driven decision-making than the private sector firms who design the city. But some understand the opportunity. Vannevar Technology is working on it, as is Synthicity. There’s plenty of room for the most positive aspects of tech culture to remake the profession of urban planning itself. (Look to NYU’s Center for Urban Science and Progress and the University of Chicago’s Urban Center for Computation and Data for leadership in this space.)

And what about the built things themselves, actual physical architecture? Where is the technology that causes us to rethink our domiciles and places of work, recreation and worship in the ways we’ve remade communications, mobility, and manufacturing in the last decade? Where are the tools that make urban districts as responsive to changing uses as metal and glass have been made malleable by 3D design tools? Where, to put it most like a William Gibson novel, is the “architecture that flickers and buzzes like faulty neon, that is washed with intermittent static like a weak video signal”?

Architect Doris Sung, for example, has begun experimenting with materials that change shape based on external stimuli, much like human skin. And it’s not just materials science, but high technology as well: the increasing instrumentation of cities with sensors and actuators creates a literal platform for designing new experiences. This is what technology startups in particular are good at.

——

Scientists have a term called “positive suboptimality” which refers to the resilience of systems which are not specialized for a particular use (or which at least weather changes in external conditions without breaking). Most often this concept is used to describe how nature has evolved not with the fittest organisms but with those fit enough to survive changing conditions. Super-specialization means extinction.

It’s a concept that could usefully be applied to cities. Precisely the way cities fall short of perfection is what gives them resilience and opens up opportunity where none previously existed. What appears broken and yet persists in cities may simply be evidence of fault-tolerance, something all technologists strive for with their products.

Molly Turner nails why this so rubs some technologists the wrong way:

[T]ech innovators also like to work on a tabula raza, void of constraints, preconceived obstacles or even the benefit of institutional knowledge. And while sometimes that leads to genius strokes of ingenuity, other times it means unknowingly repeating mistakes of our urbanist past, such as becoming overly reliant on the wisdom of the crowd or failing to account for important social or cultural divides.

Understanding how cities bend but don’t break, understanding how they do indeed break, and understanding how much of where we live influences the solutions we try to fit to problems are the greatest lessons that tech can take from urbanism.

City officials are often asked “how do you turn this place into the next Silicon Valley”? Most smart folks in economic development answer by saying that they don’t want to. They want their city to capitalize on its own legacy, assets, work ethic and skills. For many years that statement was just politicking and boosterism. But it isn’t anymore. Cities are where the problems exist and where the talent is moving. It’s easy to see how this equation sums and time for tech culture to do the math.

Giftmix 2013 (Holiday Edition)

As 2013 winds down it is time for the annual reliving-making-cassette-mixes-for-friends moment. It’s really for me. I’m unwilling to give up on that visceral joy of stitching tunes together as a gift. However, this year, instead of mashing up music that my family enjoyed during the preceding year I’m giving in to listener feedback and actually posting holiday music.

This particular half hour comes from a fun evening of back-and-forth joint DJ’ing the OpenGovChicago Holiday Party on Dec. 12 with DJ C, aka Jake Trussell. Jake’s set is not online, but his warmup is.

Holiday Tunes Past, Future and Which Should Never Have Been by Immerito on Mixcloud

Very best to you in 2014!

10,000

I’m coming up on my tenth anniversary as a Flickr user and just posted my 10,000th photo. Actually it is not a photo but a short clip of the CTA Holiday Train rolling in to Belmont station on the Purple Line. I’m especially pleased with a fairly useful application of the iPhone 5S slow-motion video: though the train is coming in quickly, you get to see St. Nick nice and clear.

Flickr has been through the ringer in the last few years. Yahoo has not been kind. And the changes since Marissa Mayer has taken over, while positive in that Flickr is getting attention, leave me scratching my head a bit. Yet, Flickr contains the memories of my last decade and I still don’t know of another service that offers the kind of tools that the site does. I’ll be with Flickr until the end — mine or its. (Backing up frequently of course).

Lost in Space, Ascent Stage edition

Got the urge to muck with the Lost in Space theme recently. I loved the re-runs of that show growing up (and have deliberately forgotten that a movie was made of it in the 90’s). The theme I used began with the show’s third season.

The title track is tiny, just one minute long with an unfortunate or awesome (your pick) Austin Powers breakdown in the middle, so there wasn’t much to work with. The arpeggios are emblematically spacey to me so I ran with that. I replaced The Robot with Siri, the panicky AI of our time (especially when using Apple Maps).

I really should embed this on this site’s 404 page.

What the public way means in the networked age

Let’s start here. I want our relationship with public objects to feel like this.

It does not feel like this currently.

But let’s back up to a street scene in Chicago in the late 1930’s for context.

You’re walking at a clip downtown because it’s storming. You hunch over and tilt your umbrella into the sheeting rain as people scamper for cover and taxis. Luckily your destination is this building and you know, thanks to having walked this route before (and a clever architect), that you don’t even have to look up to figure out that you’ve arrived.

On both the Clark and LaSalle sides of the Field Building (as it was originally known) are symbols in the sidewalk pointing to the entrances. F for Field, arrows for which way to turn.

If noticed at all, these small, plain sidewalk icons could easily be mistaken for architectural decoration. But they were designed specifically around the umbrella use-case.

You may also have seen compass markings in the sidewalk just as you step out of a subway stop. Easy to overlook, but incredibly useful if you’re disoriented emerging onto the surface grid.

These examples represent embedded, passive information that’s not screaming for attention but placed precisely where you might need it. It’s information design in the physical architecture of the public way.

Today there’s a new usage scenario. You’ve seen it a thousand times. Urban pedestrians staring down at their smartphones, half-in and half-out of the moment in what Amber Case calls “temporarily negotiated private space”.

Maybe the F-marks would be missed by these otherwise engrossed city-goers, but they are a great example of ambient information in city environments. And we’re going to need a lot more of that as we increasingly negotiate our public space through a mixture of physical and digital awareness.

What’s new is the sheer volume of mobile, networked technology in our public spaces (and everywhere else). It’s an opportunity to “embed” information in new ways and to customize it to very specific places and moments in time.

Typically sensors and wireless connectivity claim the spotlight in discussions of the networked city, but I’d argue we’re missing a real opportunity not to use new technology to make the built environment more legible.

Why?

Most obviously, embedded digital information can aid in safety. The video of the girl in China on the phone falling through the sidewalk is one end of a spectrum of examples, most of which are instances of obliviously texting pedestrians falling off piers, walking into traffic, or smashing into one another. And it’s probably getting worse.

Rudimentary systems that might prevent such calamity do exist, but with a focus on motorist, rather than pedestrian, alertness at crosswalks. Crosswalks and Xwalk both flash lights to make the zebra stripes more prominent. You could imagine a more nuanced system which assumes pedestrians are looking down (at their devices) and flashes or changes color when the traffic signal is about to turn green. Interaction with devices via Bluetooth or NFC is not inconceivable either. Scenario: if the device is engaged in use, assume distraction, and alert accordingly. A responsive public way that’s in a positive feedback loop with its users.

Accessibility is another category of use for the responsive public way. Crosswalk design for the visually-impaired is not a problem for individual intersections — high-pitched chirping signals — but it doesn’t scale for large cities. The cacophony of a city full of bleating traffic signals would be the kind of noise pollution that causes New York City to impose fines on honking motorists. But if the crosswalk itself was open to digital development you could imagine white canes, phones or other personal devices alerting the visually-impaired pedestrian that the street was open to cross.

Basic convenience may be an even better rationale for a legible (and writable) public way. Why perform a digital transaction at a modern-day parking meter when you can text it or use an app to pay before leaving your car? Think driving snowstorm. Think having three kids in the backseat and the meter is 100 meters away. Think not having a credit card at all. All good reasons. This is getting closer to the high-five moment of a digital public way.

If we begin to think of a truly responsive public way we have to rethink what “public” means in the digital age. The analogy here is a city’s information. Getting at a city’s vital signs and the records of public servants has been a long slog for transparency advocates. In the days of exclusively paper-based record-keeping Freedom of Information legislation was one of the only ways to do anything with public records. Then came digitization and the same barriers obtained. You had to go through legal maneuvers to get at it — and even then it was not particularly useful beyond reading it. PDF’s largely made this information static, opaque to computer-aided parsing and tabulation. But the advent of machine-readable online document standards and a shifting political climate towards the value of open government has unlocked torrents of data in cities around the world. What’s come of this can only be described as a new kind of civic engagement: open data has bred an ecosystem of secondary applications, analysis, and interactions that governments could never conceive of, much less produce themselves.

The infrastructure and objects of our current public way are in their paper period.

Certainly, there are screens scattered throughout. Public transit leads the way here. Buses that generate location data, subway platforms that announce arrival times, etc. There’s some digital marketing along the way that occasionally serves up alerts or public service announcements. And every so often you’ll see an advertiser attempt something (barely) interactive — a QR code for more information, typically. But there’s no platform in the software and open data API sense of the word in the physical city.

And yet, many of our public objects are networked — the foundational requirement for a responsive system. Public bikes and bike stations, bus shelters, parking meters, and of course every light pole with a public access point clamped to it — all these things are network endpoints. But they’re not interconnected and they are not open to interaction. There’s no interface for third-party development.

Some City of Chicago Department of Transportation construction projects feature NFC and QR codes on signage onsite that link to information about the project. That’s the paper stage, incunabula. The vision is for direct access to mobile-optimized applications for business permits in situ. More promisingly, the information system underlying the upcoming roll-out of public bike sharing in Chicago (e.g., real-time bike availability info) has an open API. 4,000 bikes and 400 stations will be open to development and interaction in the way that the city’s open data portal is. A step away from paper towards platform.

There’s an inverse to this dynamic, equally ripe with opportunity. The impact of city-dwellers’ use of digital technology when out-and-about has yet to make a any real impact on physical urban design. Mayor Nutter of Philadelphia got a good laugh last year when he released an April Fools Day video touting newly-striped “texting lanes” on sidewalks. But that was parody (though thinking about it a little longer makes it slightly less parodic).

Surpassingly few cities and urban design firms actually give thought to how technology is changing the way the city is used. Which is odd, since so many of the problems that online companies grapple with — what it takes to create a vibrant, safe public space, as one example — have pretty well been solved, if not perfected in implementation. There’s the Facebook approach, which is essentially suburbia: a gated network of affinity that disallows chance encounter and serendipity. And there’s the Twitter approach which is all about non-reciprocal engagement and diversity. (It’s no coincidence that the founder of Twitter is a dilettante urbanist.) This is a choice between mall culture and real urbanism and I fear that our information architects and built environment architects have not even begun the conversation.

The sidewalk is the original social network and its lessons have much to teach the designers of our digital overlay of public spaces.

In Chicago, it’s coming together: a robust open government community of engaged developers (and increasingly savvy residents) fueled by an administration actively publishing data and working to make sure the vendors of our public objects treat it as a platform. There’s a long way to go, but we’ve etched some symbols in the pavement and we’re hoping you follow our lead.

High five!

(X * X = Chicago). Solve for X.

Recently, as we sometimes do to fill time, my family and I were asking each other trivia questions. My six-year-old daughter piped up with one from left field that made me laugh out loud — then had us thinking for the rest of the evening. She asked:

What’s the square root of Chicago?

Didn’t have an answer for that one, but it was ready-made for my Twitter followers and they did not disappoint.

The literalists looked at ranking and square mileage, but perhaps this town if squared might be us:

@immerito it’s Sunbury, North Carolina population 1,645

— Zach Kaplan (@zkaplan) February 17, 2013

Some took a geographic angle. Logan Square, the Loop itself and my favorite:

@immerito Fort Dearborn. It was a square. Planted the roots of our city. twitter.com/tomkompare/sta…

— tom kompare (@tomkompare) February 18, 2013

The most interesting approach was formulated by Seth Lavin. He put it two ways:

For the verbal minds, it’s whatever makes this sentence true: “In Chicago, we blank blank.” (e.g. we reform reform)

In other words, (X * X = Chicago). Solve for X?

It’s a head-scratching formulation, in some ways. What thing, what action, what verb does Chicago do to the same thing, action, verb that makes this city uniquely us?

Some suggestions:

- defeat defeat

- discriminating discriminators

- perfect perfection

- disempower disempowerment

- build buildings

- plant plants

- bully bullies

- reform reform

- red line (huh?)

No clear winner to my mind, but I sure did like Josh Davison’s wordplay: “polish Polish”. As in polish off Polish sausage. My wife noted that the reverse has been historically true with Polish housekeepers being employed to polish things (among other tasks).

All good fun, of course, but this exercise may be an epiphenonemon of the very real debate over whether cities can be mathematically described in a useful way. That’s quite another post. For now let’s revel in the oddball question of a six-year-old kid.