Speechifying

Lotta public speaking in the next few weeks. Most are local. If you’re interested in technology and urbanism come on out for a conversation.

University of Illinois Chicago College of Urban Planning Friday Forum

Friday, Feb. 24, 12p

“Data-Driven Chicago”

[detail]

University of Chicago Computation Institute Lecture

Monday, Feb. 27, 4:30p

“The City Is a Platform”

[detail]

City Club Public Policy Luncheon

Tuesday, March 6, 12p

[detail]

South by Southwest Interactive

Austin, TX

Monday, March 12, 12:30p

“The Future of Cities: Technology in Public Service”

[detail]

I’m particularly excited about that last one as I get to share a panel with Chris Vein, Nick Grossman, Abhi Nemani, Nigel Jacob, and Rachel Sterne. Perhaps the conversation will focus on just what the hell I am doing on the same stage as such accomplished folk. If you’ll be at SXSW, you should definitely drop by for this one.

Update from Beat Research Outpost #2

The Chicago incarnation of Beat Research has hit full stride. Jake, Jesse, and I are now in a twice-monthly groove (ahem) at Villains in the South Loop. And the first Wednesday of each month we overlap with the fantastic Urban Geek Drinks. All I need is for a NASA meetup to move in and I’ll pretty much have every interest covered.

Here’s my set from last night. Sanford & Son, music for Sith lords, 1980’s classics, my first foray into house (I know, right?) and of course some Chicago love. Do enjoy.

Beat Research Chicago begins

Here’s part of my set from the inaugural Beat Research Chicago at Villains last night. Fairly stompy with a bit of dubstep, drum and bass, and crazy Facebook users thrown in.

It’s the first time I’ve used Ableton with Serato in a live setting. Not a complete trainwreck. There’s hope.

Details and upcoming show info here.

Open data in Chicago: progress and direction

In a wonderfully comprehensive overview of Government 2.0 in 2011 up at the O’Reilly Radar blog Alex Howard highlights “going local” as one of the defining trends of the year.

All around the country, pockets of innovation and creativity could be found, as “doing more with less” became a familiar mantra in many councils and state houses.

That’s certainly been the case in the seven-and-a-half months since Mayor Emanuel took the helm in Chicago. Doing more with less has been directly tied to initiatives around data and the implications they have had for real change of government processes, business creation, and urban policy. I’d like to outline what’s been accomplished, where we’re headed and, importantly, why it matters.

The Emanuel transition report laid out a fairly broad charge for technology in his office.

Set high standards for open, participatory government to involve all Chicagoans.

In asking ourselves why open and participatory mattered, we developed the following four principals. The first two, fairly well-established tenets of open government; the last two, long-term policy rationales for positioning open data as a driver of change.

First, the raw materials. Chicago’s data portal, which was established under the previous administration, finally got a workout. It currently hosts 271 data sets with over 20 million rows of data, many updated nightly. Since May 16 the portal has been viewed over 733,201 times and over 37 million rows of data have been accessed.

But it’s the quality rather than the quantity that’s worth noting. Here’s a sampling of the most accessed data sets.

- TIF Projection Reports

- Building Permits (2006 to present)

- Food Inspections

- Vacant and Abandoned Buildings Reported

- Crimes – 2001 to Present (more block-level crime data than any other city, updated nightly)

Here’s a map view of the installed bike rack data set.

As a start towards full-fledged performance management, we launched cityofchicago.org/performance for tracking most anything that touches a resident: hold time for 311 service requests, time to pavement cave-in repair, graffiti removal and business license acquisition, zoning turnarounds, and similar. Currently there are 43 measurements, updated weekly. Here’s an example for average time for pothole repair.

To be sure, all this data can be inscrutable to residents. (One critic of the effort called it “democracy by spreadsheet”.) But the data is merely a foundation, not meant as a end in itself. As we make the publication of this data part of departments’ standard operating procedure the goal has shifted to creation of tools, internally and in the community, for understanding the data.

As a way of fostering development of useful applications, the City joined its data with Chicago-specific sets from the State of Ilinois, Cook County, and the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning to launch an app development competition. Anyone with an idea and coding chops who used at least one of the City’s sets was eligible for prize money put up by the MacArthur Foundation.

Run by the Metro Chicago Information Center, Apps for Metro Chicago was open for about six months and received over 70 apps covering everything from community engagement to sustainability. (You can find the winners for the various rounds here: Transportation, Community, Grand Challenge.)

Here are some of my favorite apps created from the City’s open data.

- Mi Parque – A bilingual participatory placemaking web and smartphone application that helps residents of Little Village ensure that their new park is maintained as a vibrant safe, open and healthy green space for the community.

- SweepAround.us – Enter your address, receive an email or text message letting you know when the street sweepers are coming to your block so you can move your car and avoid getting a ticket.

- Techno Finder – Consolidated directory of public technology resources in Chicago.

- iFindIt – App for social workers, case managers, providers and residents to provide quick information regarding access to food, shelter and medical care in their area.

The apps were fantastic, but the real output of A4MC was the community of urbanists and coders that came together to create them. In addition to participating in new form of civic engagement, these folks also form the basis of what could be several new “civic startups” (more on which below). At hackdays generously hosted by partners and social events organized around the competition, the community really crystalized — an invaluable asset for the city.

Open data hackday hosted by Google

Beyond fulfilling a promise from the transition report, why is any of this important? The overarching answer is not about technology at all, but about culture-change. Open data and its analysis are the basis of our permission to interject the following questions into policy debate: How can we quantify the subject-matter underlying a given decision? How can we parse the vital signs of our city to guide our policymaking?

The mayor created a new position (unique in any city as far as I know) called Chief Data Officer who, in addition to stewarding the data portal and defining our analytics strategy, is instrumental in promoting data-driven decision-making either by testing processes in the lab or by offering guidance for problem-solving strategies. (Brett Goldstein is our CDO. He is remarkable.)

As we look to 2012, four evolutions of open data guide our efforts.

The City-as-Platform

There are a variety of ways to work with the data in the City’s portal, but the most flexible use comes from accessing it via the official API (application programming interface). Developers can hook into the portal and receive a continuously-updated stream of data without manually refreshing their applications each time changes happen in the feed. This changes the City from a static provider of data to a kind of platform for a application development. It’s a reconceptualization of government not as provider of end user experience (i.e., the app or service itself), but as the provider of the foundation for others to build upon. Think of an operating system’s relationship to the applications that third-party developers create for it.

Consider the CTA’s Bus Tracker and Train Tracker. The CTA doesn’t have a monopoly on providing the experience of learning about transit arrivals. While it does have web apps, it exposes its data via API so that others can build upon it. (See Buster and QuickTrain as examples.) This model is the hybrid of outsourcing and civic engagement and it leads to better experiences for residents. And what institution needs a better user experience all around than government?

But what if all City services were “platform-ized” like this? We’re starting 2012 with the help of Code for America, a fellowship program for web developers in cities. They will be tackling Open 311, a standard for wrapping legacy municipal customer service systems in a framework that turns it too into a platform for straightforward (and third-party) development. The team arrives early in 2012 and will be working all year to create the foundation for an ecosystem of apps that will allow everything from one-snap photo reporting of potholes to customized ward-specific service request dashboards. We can’t wait.

The larger implications of platformizing the City of Chicago are enormous, but the two that we consider most important are the Digital Public Way (which I wrote about recently) and how a platform-centric model of government drives economic development. Bringing us to …

The Rise of Civic Startups

It isn’t just app competitions and civic altruism that prompts developers to create applications from government data. 2011 was the year when it became clear that there’s a new kind of startup ecosystem taking root on the edges of government. Open data is increasingly seen as a foundation for new businesses built using open source technologies, agile development methods, and competitive pricing. High-profile failures of enterprise technology initiatives and the acute budget and resource constraints inside government only make this more appealing.

An example locally is the team behind chicagolobbyists.org. When the City published its lobbyist data this year Paul Baker, Ryan Briones, Derek Eder, Chad Pry, and Nick Rougeux came together and built one of the most usable, well-designed, and outright useful applications on top of any government data. (Another example of this, from some of the same crew, is the stunning Look at Cook budget site.)

But they did not stop there. As the result of a recent ethics ordinance the City released an RFP to create an online lobbyist registration system. The chicagolobbyists.org crew submitted a proposal. Clearly the process was eye-opening. Consider the scenario: a small group of nimble developers with deep subject matter expertise (from their work with the open data) go toe-to-toe with incumbents and enterprise application companies. The promise of expanding the ecosystem of qualified vendors, even changing the skills mix of respondents, is a new driver of the release of City data. (Note I am not part of the review team for this RFP.)

One of the earliest examples of civic startups — maybe the earliest — is homegrown. Adrian Holovaty’s Everyblock grew out of ChicagoCrime.org, which itself was a site built entirely on scraped data about Chicago public safety.

For more on the opportunity for civic startups see Nick Grossman’s excellent presentation. (And let’s not forget the way open data — and truly creative hacker-journalists — are changing the face of news media.)

Predictive Analytics

Of all the reasons for promoting a culture of data-driven decision-making, the promise of using deep analytics and machine learning to help us isolate patterns in enormous data sets is the most important. Open data as a philosophy is easily as much about releasing the floodgates internally in government as it is in availing data to the public. To this end we’re building out a geo-spatial platform to serve as the foundation of a neighborhood-level index of indicators. This large-scale initiative harnesses block- and community-level data for making informed predictions about potential neighborhood outcomes such as foreclosure, joblessness, crime, and blight. Wonkiness aside, the goal is to facilitate policy interventions in the areas of public safety, infrastructure utilization, service delivery, public health and transportation. This is our moonshot and 2012 is its year.

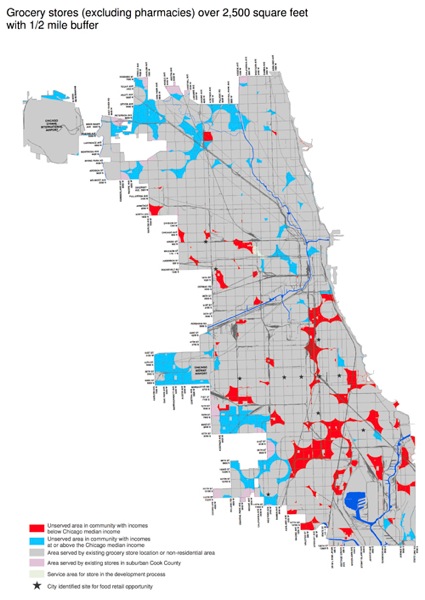

Above, a very granular map from early in the administration isolating food deserts in Chicago (click image for larger). It is being used to inform our efforts at encouraging new fresh food options in our communities. This, scaled way up, is the start of a comprehensive neighborhood predictive model.

Unified Information

The same platform that aggregates information geo-spatially for analytics by definition is a common warehouse for all City data tied to a location. It is, in short, a corollary to our emergency preparedness dashboards at the Office of Emergency Management and Communication (OEMC), a visual, cross-department portal into information for any geographic point or region. This has obvious implications for the day-to-day operations of the City (for instance, predicting and consolidating service requests on a given block from multiple departments).

But it also is meaningful for the public. Dan O’Neil recently wrote a great post on the former Noel State Bank Buiding at 1601. N. Milwaukee. It’s a deep dive into the history of a single place, using all kinds of City and non-City data. What’s most instructive about the post is the difficulty in aggregating all this information and the output of the effort itself: Dan has produced a comprehensive cross-section of a small part of the city. There’s no reason that the City cannot play an important role in unifying and standardizing its information geo-spatially so that a deep dive into a specific point or area is as easy as a Google search. The resource this would provide for urban planning, community organizing and journalism would be invaluable.

There’s more in store for 2012, of course. It’s been an exhilarating year. Thanks to everyone who volunteered time and energy to help us get this far. We’re only just getting started.

Reascent

Quick note about changes to the blog.

I’ve moved everything over from a Movable Type installation to the WordPress platform — something I have put off doing for years. I loved MT in the early years, but upgrades and patching became increasingly onerous, as the community of developers and support dwindled. So, yeah, WordPress.

The irony is that most of the pain of the transition was in ensuring that nothing much changed. The biggest hurdle was ensuring that the permalink structure of MT carried over for archived posts so indexed and internal URLs did not break. So, though the MT-to-WP import worked well, I had to touch every single post to make sure the permalink was correct. Add in various formatting issues and it was pretty hellish.

I got at least one inquiry this year about whether my new job at the city had forbidden me from blogging. That’s absolutely not the case. It was a combination of an increasingly-crufty blog platform, the way Twitter allows you to post an idea without actually fleshing it out, and just the timesuck of getting my feet at the city.

But that’s all fixed now. I fully intend to return Ascent Stage to the mix of way-too-long essays and who-cares ephemera that has characterized it in the past.

Not all the functionality (or design) of the old site is replicated here — and I am not entirely sure I got all the broken internal links. (External linkrot, well, that’s just the way of the Internet.) But it should be fairly stable.

Some reminders of other tendrils on the web:

Also, here’s my really big head on a “personal page”.

Do enjoy.

“Musical quality above genre coherence”

Pleased to announce that my pals Jake and Jesse and I will be hosting a local version of the venerable Beat Research.

On the first and third Wednesdays of the month we’ll deliver a few hours of experimental party music at Villain’s in the South Loop.

Jake (DJ C) started Beat Research in Boston in 2004 with Antony Flackett (DJ Flack) as a base for the genre-bending sets of music the two had been playing since the late ‘90s.

Since inception, Beat Research has hosted some of the best and brightest DJs and producers of underground bass music in the world, given a number of young luminaries their first gigs, and presented an utterly motley collection of tech-addled live performances. The long list of special guests includes DJ Rupture, Kingdom, Eclectic Method, Ghislain Poirier, Vex’d, edIT, and Scuba.

DJ C has since moved to Chicago (replaced by the incomparable Wayne Marshall) and, having missed those heady days in the Beat Research DJ booth, didn’t need much encouragement to be persuaded that this city could use its own explorations into innovative dance music.

Beat Research has been hard to match for anyone seeking out extraordinary sounds. Now Chicagoans can look forward to their own weekly session for discerning dancers and enthusiastic head-nodders.

More information and a mailing list sign-up at Beat Research Chicago. Toots at @beatresearch.

See you there, Chicago.

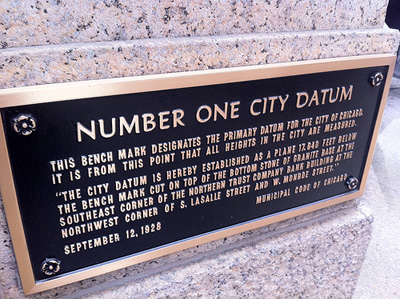

Municipal devices

There’s a somewhat unknown symbol of Chicago called the “Municipal Device”. Basically a Y in a circle. It’s a representation of Wolf Point, where the main, north, and south branches of the Chicago river converge. It’s not nearly as ubiquitous as the Chicago flag or the city seal, but it’s actually all over the place if you look carefully. It’s embedded in building facades, attached to an occasional streetlamp, and the logo of the Chicago Public Library. (It’s even part of a light pouring through the girders of the Division Street Bridge.)

If you know me well enough you’ll understand that the very idea that Chicago has a municipal device that’s embedded in the built environment but seldom noticed is appealing on all kinds of levels.

Surely you see where I’m headed with this.

In the case of the symbol the word “device” is a throwback to heraldry. But what about the more typical definition, a functional device? What examples of this are specifically in the service of the municipality?

Let’s start at street level. The public way currently hosts plenty of digital, networked objects.

Photos: left by Flickr user Sterno74, upper right by Chicago Tribune

There are 4,500 networked (solar-powered) parking meters on city streets. The CTA is outfitting train platforms and bus shelters with digital signage with transit information. Even some of our public trash cans are networked objects.

Add to these public shared bike stations (coming soon), all the non-networked screens on the sides of buses and buildings, and infrastructure systems like traffic signal controls, snowfall sensors, streetscape irrigation, and video cameras.

Lastly — and most importantly — are the legions of networked people walking down any given street. Smartphones turn a sidewalk of pedestrians into a decentralized urban sensor network. (A topic for a future post.)

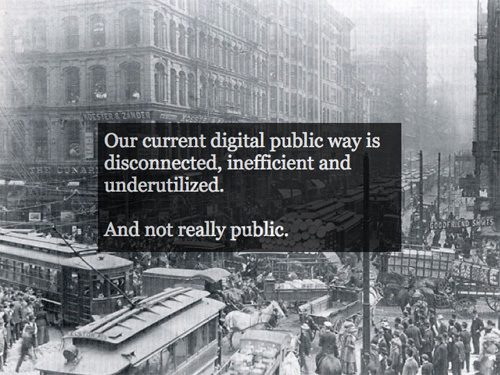

The point is, none of these municipal devices are interoperable, very few work from a common platform, and only a handful are actually open in the sense that a sidewalk is open and public.

How the physical public way is actually used is a good model as we consider what a real digital public way comprised of these disarticulated “devices” might be like. The sidewalk, for instance, is a public space with fairly liberal parameters for usage. Beyond being a route for perambulation it’s a place for free speech and protest, vending, chalk artistry, flâneurism, kids’ lemonade stands, café seating, poetry distribution, busking, throwing bags, chance encounter, and all sorts of other things. Public space in general is the primary mode of information throughput in an urban area.

The question we’re asking ourselves at the city is, how would a digital public way that seeks this level of openness and breadth of use actually work? And what would city government need to do to ensure that the best foundation is laid for this to come to pass? (We’ve begun design and have a few early-stage pilots planned, but my hope with this post is that it begins the conversation broadly about what could and should be.)

Here’s a very low-tech example of a networked public object. All bus stops in the city have signs with a unique SMS shortcode. Waiting riders can text this number for a list of upcoming buses and times. Conceptually this is a one-on-one networked interaction between a person and a public object, the sign. (Technically of course it involves a wide-area network, but we know that near-field communication is on the horizon, and coming to the CTA.)

One way to think about a digital public way is to ask what benefits would accrue to residents and visitors if all public objects were queryable like this. It makes sense for transit, possibly even with certain of the city’s service vehicles, but that seems a limited way of interacting with a municipal device: one-way and purely informational.

There are two other ways of thinking about an open digital public space, it seems to me, and they both have to do with thinking of the city as a platform for interaction.

Photo by Jack Blanchard

The first is to recognize that interaction with all forms of government is increasingly happening online and/or via mobile devices. For instance, plenty of cities have mobile service request (e.g., pothole reporting) smartphone apps. If we think of the currently-installed devices listed above as merely end-points for a network connection to be built upon the city becomes a kind of physicalized network, a platform, for other uses. What might it mean to extend the currently-proprietary network connections for these devices for extremely local, public use? What might it mean for digital literacy in our communities if service requests could be made at the physical locations that they are needed? Thinking of these thousands of points of network tangency enables a scale of functionality that no website or mobile app ever could.

The second is also about platforms. Chicago’s open data portal hosts hundreds of regularly-updated, machine-readable data sets. These sets are the vital signs of the city: public safety, infrastructural, educational, business data, and on and on. They also represent a platform for creating new things. Developers can access the data directly via the portal’s API (application programming interface), building apps that provide new functionality and in some cases radically new uses of the data. (The Apps for Metro Chicago competition hosts a good gallery.)

Now conceive of the city itself as an open platform with an API. Physical objects generate data that can be combined, built upon, and openly shared just as it can be from the data portal. The difference in this scenario is location. Where much of the data in the portal is geo-tagged, data coming from the built environment would be geo-actionable. That is, in the city-as-platform scenario certain data is only useful in the context of the moment and the place it is accessed.

Photo by Jen Masengarb

Here’s a simple example.

The bus shelter you’re waiting at informs you (via personal device or mounted screen) that the public bike share rack at your intended destination is empty. It suggests taking a different bus only a minute behind the one you are waiting for in order to access a bike a few blocks from where you had intended. It offers to reserve the bike to ensure its availability and sends you a map of protected bike lanes (plotted to avoid traffic congestion around a street party) that you can use to reach your final destination.

What’s key about this is the diversity of data sources involved — real-time bike rack status (and reservation), bus locations, route info, protected bike lane locations, traffic volumes and incidents, and cultural event data — but also the fact that it would be nearly meaningless in any place but that exact shelter.

This scenario is the result of a network of interlinked municipal devices. But it needn’t be city government that creates such a scenario end-to-end. By exposing and documenting the data that makes the above possible (as we do with Bus Tracker and Train Tracker) we would enable developers to create their own ecosystem of applications. It’s a business model and the driver of the emergence of civic startups.

You could call such a set of open, networked objects the beginning of an urban operating system and certainly there’s another discussion entirely to be had around how what I’ve described forms the basis of a common operations platform for managing city resources internally. But I’m growing skeptical of calling all this an operating system, at least in the sense we traditionally do. Much of the talk of an urban OS focuses solely on centralized control. But if you’re true to the analogy of a computer operating system it would have to be a platform for others to build applications upon. In truth, this is a lot more like a robustly deployed, well-documented set of fault-tolerant API endpoints than it is an OS.

On the original Y-shaped municipal device there’s an odd slogan that sometimes accompanies it: I Will. It’s a quotation from a turn-of-the(-last)-century poem by Horace Fiske. If you can get past its priapismic opening and closing lines, you’ll find a pretty forgettable example of overly-gilt regionalist verse.

It’s curious. I will what? In the poem, Chicago, embodied as a goddess, seems to be saying that she will “reach her highest hope beyond compare”. Which doesn’t really say anything at all. What does she hope for?

What would you hope for in a city of networked municipal devices?

Giftmix 2011

Pretty sure there’s at least a few naughty among you, but here’s the annual giftmix just the same. Happy holidays and best in 2012, friends.

Tracks:

This City Is Killing Me – Dusty Brown

Seeing the Lines – Mr. Projectile

Futureworld – Com Truise

Unbank – Plaid

Daydream – Tycho

German Clap – Modeselektor

Spacial – Tevo Howard*

Rubin – Der Dritte Raum

Human Reason – Adam Beyer

Planisphere – Justice

Genkai (1) – Biosphere

* Chicago artist

The kind of Innovation Chicago is

The economist Edward Glaeser has called Chicago “a city built upon corn in porcine form”. He’s referring to the city’s remarkable 19th century transmutation of the natural bounty of prairie agriculture into a higher value form of commerce, pigs. The innovation necessary for the cold storage and transportation of which would help Chicago become the central node in a nation-spanning rail network. It was the beginning of greatness.

We can effect this transformation again. Our natural bounty today is data, knowledge, and ideas — their “form” the establishment of new businesses and a more livable Chicago.

Today Chicago gets a new mayor and a new administration. I’m proud to be its Chief Technology Officer, a role I took for a single, simple reason. For the last three years I have traveled the world consulting with cities on strategies for making them smarter, more efficient, and more responsive to citizens. Many of these talks and projects were fruitful, but none of them mattered to me personally. None of them, in short, mattered to the city I love most.

The coming of the web, you may recall, was cause for all kinds of pronouncements that we’d move away from each other, tied only by network communications, happily introverted in electronic cocoons. This has not happened (indeed the reverse is happening). If anything the ubiquity of network technologies has proven that place matters. Mobile computing and “checking-in”-style apps are ascendant because we are creatures of place. And my place, the place of four generations of my family, is Chicago. It’s time to focus my effort here.

The transition report published last week is a roadmap for the change the Emanuel administration will undertake. All of the initiatives are exciting and important, but one speaks directly to remaking Chicago as a hub of information that leads to insight and growth.

Set high standards for open, participatory government to involve all Chicagoans

Why do this?

Without access to information, Chicagoans cannot effectively find services, build businesses, or understand how well City government is performing and hold it accountable for results.How will we do this?

The City will post on-line and in easy-to-use formats the information that Chicagoans need most. For example, complete budget documents – currently only retrievable as massive PDF documents – will be available in straightforward and searchable formats. The City’s web site will allow anyone to track and find information on lobbyists and what they are lobbying for as well as which government officials they have lobbied. The City will out-perform the requirements of the Freedom of Information Act and publicly report delays and denials in providing access to public records.The City will also place on-line information about permitting, zoning, and business licenses, including status of applications and requests. And Chicagoans will be asked to participate in Open311, an easy and transparent means for all residents to submit and monitor service requests, such as potholes and broken street lights. Chicagoans will be invited to develop their own “apps” to interpret and use City data in ways that most help the public.

Participatory government isn’t the only use of the wealth of information the city can publish. We intend data-driven decision-making, powered by deep analytics of our services and city vital signs, to be central to the day-to-day business of running Chicago.

A data-centric philosophy is more than transparency and efficiency, too. It is about fostering innovation. Business is built on local resources. Where once we transformed grain into pigs into commodities, we can now provide data that serves as a kind of raw material for new business and new markets.

(One example of this — and proof that the talent to do great things is right here, right now — is the design of a “smart intersection” by the students from George Aye’s Living In A Smart City class at the School of the Art Institute this semester.)

There’s plenty more in store for technology to assist in Chicago’s growth and livability. It’s suffused throughout the transition report: promoting entrepreneurship, increasing access to broadband, treating the street as a platform for interaction itself (more of which on all these in future posts). But the foundation is data. Access is an important first step, followed quickly by the tools and policies for taking action on it.

Chicago knows how to do all this. We’ve been doing it for over a century. We have the talent in the private sector, in academia, and in our non-profits to capitalize on any impetus city government can give. Let’s get going.

On Leaving IBM

Today, May 12, is my last working day with IBM, my employer for the last 13 years. It’s tough to adequately express how many opportunities IBM has afforded me and how difficult it was to make the decision to depart.

What follows is my shot at the first. I’ll let you guess at the second. (Hint: If you’re looking for a juicy exposé or vindictive exit letter, this ain’t it.)

1998, Georgia Tech: I was finishing up a masters degree that didn’t exist three years prior. The tech bubble had not burst and everyone in the circles I moved in was decamping for the world of stock options, foosball tables, and the promise of becoming the next Netscape.

I had two offers on the table, one from a classic dotcom agency, and one fromIBM, a classic old person company. I struggled mightily with the decision and frankly I still don’t know exactly why I chose IBM. Might have been the I in the acronym — the suggestion of a career spent globetrotting and doing business in different cultures. But I do know that the other company ceased to exist only a few years later.

IBM then was a resurgent corporation back from the brink of death. Atlanta was the home to its Interactive Media organization, a kind of skunkworks dotcom agency — which I joined as a producer. (We had so few models internally for the web work we were doing that we borrowed titles from flim: producer, executive producer, even continuity director.) It was frenetic, design-oriented, and full of lots of people who very definitely were not old. (And neither was I. Dig the hair!)

I lucked into the part of Interactive Media that was building systems for live event coverage of the sports properties that IBM sponsored, primarily pro tennis, golf, and the Olympics. This was the world before cacheing and the cloud and so a certain amount of terror accompanied the task of running websites that could handle the load of sports fans worldwide checking scores covertly from work.

We were “webcasting,” crammed into windowless rooms or awful rented trailers, but let’s face it, I was onsite at Wimbledon, the US Open, and the Ryder Cup. And loving it. The stories and friendships from those days are some of the most cherished of my career. (Someday ask me about a sopping-wet Brooke Shields hiding out in our nerd bunker during a rain delay at Flushing Meadows.)

The moment that established the trajectory that would basically define my career at IBM — diving way deep, obsessively even, into the subject matter surrounding my projects — arrived with the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. I had been tagged by colleagues as “the guy who likes books” given my undergraduate pursuits, so I suppose it is not surprising that I would be given the lead on a cultural project. It was a massive undertaking, digitizing thousands of works of art, presenting it on a still-nascent web, and working across cultural and linguistic differences. It was, in short, a template for much of the work to follow.

With one interlude. In 2000 I somehow finagled my way onto the cruise shipIBM had rented as living quarters for its guests to the Sydney Olympics. A pal and I provided tech support in the computer lab for IBM customers to check e-mail and download digital photos. (It was the era before ubiquitous laptops and connectivity, you see.) It was also, perhaps, the greatest gig of all time.

Over the course of the next many years I had the privilege of leading a number of increasingly complex projects in cultural heritage. Eternal Egyptapplied the concept of an online museum to an entire country, across multiple institutions, and nearly all historical eras. Add in mobile phone and PDAaccess (hey, it was 2003!) and a History Channel documentary and you had the making of something great.

Moving away from material culture and into the realm of society and history, I was honored to lead the team that built the website for the newest Smithsonian museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, something not set to open on the mall for several years. TheNMAAHC Memory Book was one of the first citizen-curated content projects for the Smithsonian and is a great foundation for the museum’s bottom-up presentation of the African-American experience.

More directly in the lineage of the Hermitage and Eternal Egypt, The Forbidden City: Beyond Space and Time took IBM’s cultural heritage work away from the web and into multi-user 3D space. Modeling the square kilometer of the Ming-Qing era complex was my first taste of city design and crafting spatial interactions, a foreshadowing of relatively great import.

Interspersed among the cultural work were a few important projects that were both responses to world events. The Katrina disaster mobilized a crack team in IBM to develop Jobs4Recovery, a site that aggregated and geo-located employment opportunity in the states hit by the hurricane. This was particularly meaningful to me as my wife’s family was directly, sadly affectedby the disaster and its aftermath.

Working in Egypt before and after the 9/11 attacks gave me a perspective (and friendships) for which I am eternally grateful. So it was a real pleasure to work on Meedan, a news aggregrator/social network for current events in the Middle East and North Africa. Working with the non-profit of the same name, Meedan was built to use IBM machine translation and human volunteer editors and curators to provide English and Arabic translations of news stories and comments. I had worked much of my career presenting the treasures of the world’s material culture to broader audiences; Meedan was my opportunity to widen the definition of culture that we were hoping to bridge to others.

Perhaps the most transformative moment of my career came upon being accepted to the fledgling Corporate Service Corps, IBM’s internal “peace corps”, a hybrid leadership development and philanthropic program that sent small teams of IBM’ers to areas of the world that IBM does not currently do business. I joined the first team to West Africa and was thrilled to head to Kumasi, Ghana with nine other IBM’ers from around the world. We worked with small businesses to help them on all manner of problems. Being jolted out of a comfortable office setting to find common ground with colleagues from different lines of business and other countries was amazing enough, but I had the great fortune of our former nanny in Chicago, a native of Kumasi, returning to her family there and ensuring that I not only worked in Ghana but felt a part of the community there. It changed my life.

I got my first dose of what would become a full-on obsession in modeling complex systems for better decision-making when I inherited Rivers for Tomorrow from a retiring colleague. Rivers, a partnership with The Nature Conservancy, permits users to simulate different land use scenarios in river watersheds to see what the effects are downstream, so to speak, on water quality. It was a fun set of systems to model, but much hairier problems came shortly.

The project that I end on, whose roots I trace to the Forbidden City project, isCity Forward. I consider it a kind of simulator of cities using data in the same way that the Virtual Forbidden City was one in 3D graphics. You can read all about the project — heaven knows I have talked about it enough here and elsewhere, but the key thing is the world of urbanism that it opened to me. City Forward set me on a path to relationships with people making real change in cities around the world and showed me the promise of technology embedded in the everyday lives of city-dwellers. It is, in a word, the springboard that has launched me into my new role.

I realize that’s a pretty me-focused list of experiences and I will admit that this blog post is as much a personal retrospective as anything else. But I think it does a good job of making it clear how important IBM has been to my professional development, personal growth, and intellectual satisfaction. I could not have asked for a more fulfilling past 13 years and I leave with nothing but respect and thanks for what the company has done for my family and me.

And yet the list above glaringly lacks the most important thing that I am leaving. My colleagues in IBM have, to the person, been the most meaningful aspect of my career. To list everyone who made me a smarter person, a better colleague, a more understanding manager, a more collaborative partner, or better world citizen would take several blog posts, but suffice to say that I met some of my very best friends, a few mentors, and even a few professional idols in my time with IBM. My gratitude for my colleagues at IBM exceeds my capacity to express. Thank you.

So what now? I am off to the role of Chief Technology Officer for the City of Chicago under our new mayor, Rahm Emanuel. That’s a post for another time, but it’s fair to say now that it was an offer I could not pass up. I have been preaching smarter cities for a very long time; to let an opportunity go by to take real action in the city I love most would have filled me with regret. It is time to put my money where my mouth is.

IBM turns 100 years old this summer — a fairly amazing accomplishment for any company, let alone an IT company. I’m proud of what IBM has achieved, but even more proud of the people who have done the work. I’ll leave you with this extraordinary video, the best portrait of the people of IBM that I know. And the very essence of what I will miss most.